The most ambitious urban plans often don’t materialize beyond the drawing board. Usually, it’s a funding issue, or local politics, or simply the lack of will on the part of those who are calling the shots to take up a brand new idea. Seattle, no stranger to grand urban schemes, seems to be one of those rare exceptions—the sweeping Olympic Sculpture Park by Weiss/Manfredi being a recent example. A new plan by Field Operations (James Corner) for the Seattle waterfront could well turn out to be a worthy addition. So staging an ideas competition for an underused site near Seattle’s urban core—Seattle Center—would seem like an attention-getter and harbinger of great things. As was the case with this competition, initiating a discussion about a site without imposing strict programmatic limitations can sometimes get the ball rolling. Wasn’t this how New York’s High Line got started, first raising the bar with an ideas competition until it developed into a real project?

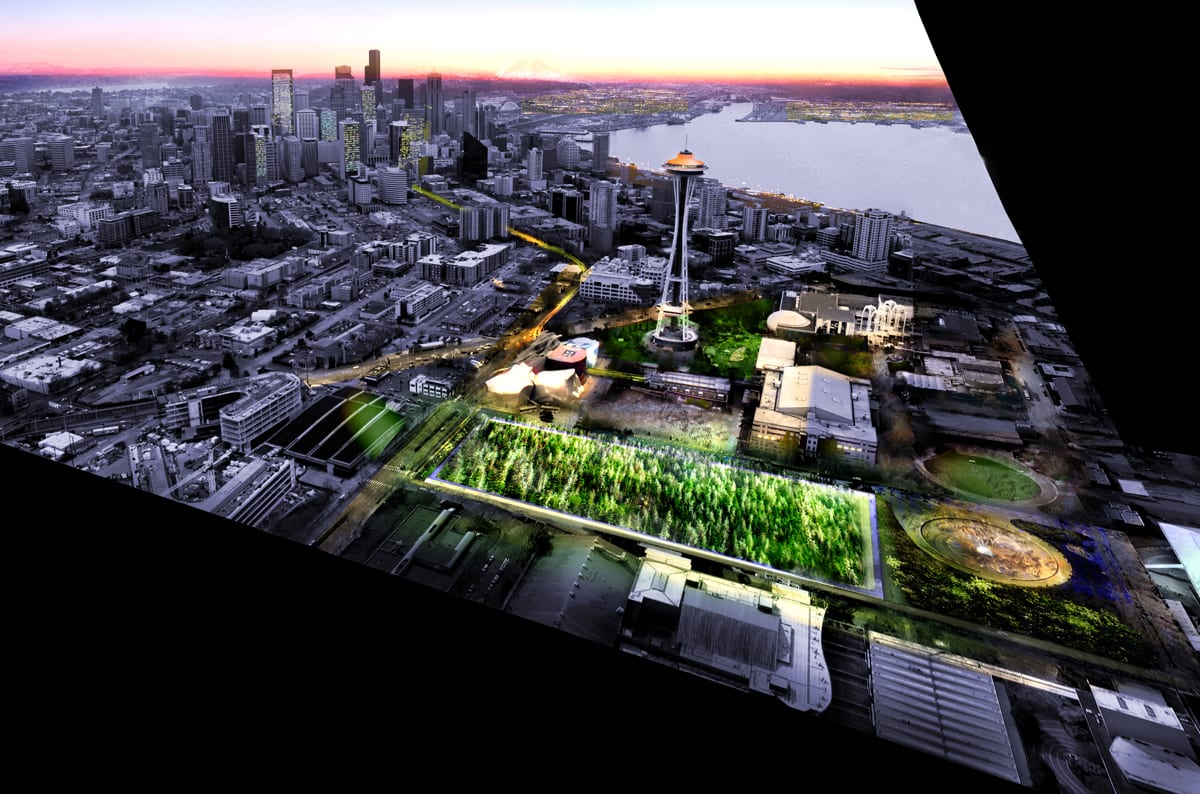

Although you’d never know it by its name, this competition was based on a 9-acre site in the northeast quadrant of Seattle Center. A legacy of the 1962 “Century 21” Worlds Fair, Seattle Center is the city’s cultural district, community festival space and park. It is now the center of 50th anniversary celebrations of the fair itself—with lots of retrospective events and nostalgia. Over the past five decades, the old fairgrounds have been reinvented and revised, with slow and deliberate interventions and judicious pruning of legacy structures. A master plan adopted in 2008 anticipated the big anniversary and the latest wave of revisions.

The designated site for the free-floating ideas in the Urban Interventions competition comes with its own very heavy baggage—an aging concrete football stadium structure that pre-dates the 1962 fair. Owned by Seattle Schools, the land cannot be cleared for redevelopment and opened up until the city-owned Seattle Center can complete some very delicate negotiations with the school district, which suffers from churning leadership and strapped finances. Negotiations will likely hinge on replacing the playfield itself somewhere on the site of the Urban Interventions design competition.

The six-member competition jury included August de los Reyes, designer, writer, and educator (Palo Alto, CA); Gene Duvernoy, president of Forterra, formerly Cascade Land Conservancy (Seattle, WA); Tom Leader, principal of award winning landscape architecture firm Tom Leader Studio (Berkeley, CA); Mia Lehrer, founder of landscape architecture firm Mia Lehrer+Associates (Los Angeles, CA); Rick Lowe, celebrated public artist (Houston, TX); and Patricia Patkau, founding partner in the firm of Patkau Architects (Vancouver, B.C., Canada). A total of $120,000 in prizes was offered, with funding from the Grousemont Foundation.

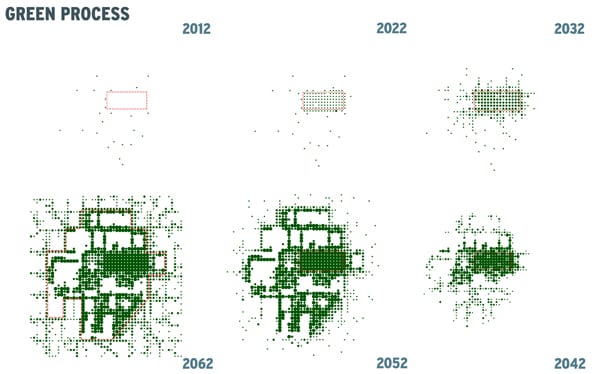

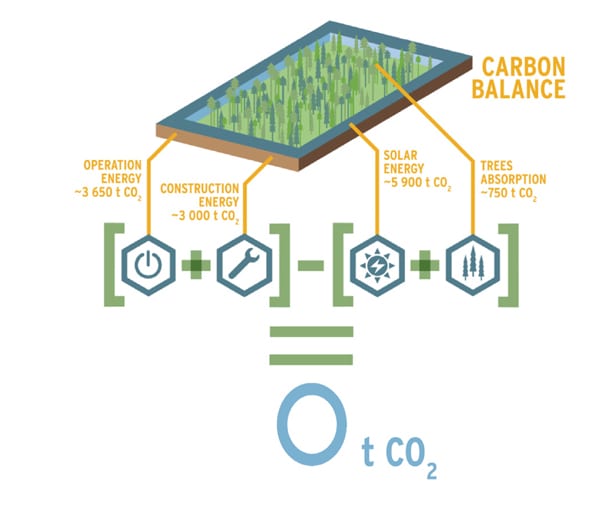

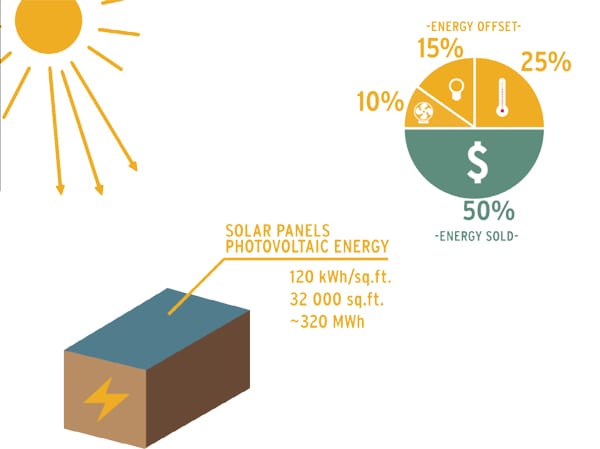

The competition itself drew 107 proposals from 24 countries, and the winning entry, [In]Closure, by a multi-disciplinary French team called ABF, is a plan for portable, modular units linked in an active perimeter around an urban forest. According to the ABF description, it’s about “de-materialization,” and it celebrates “conviviality” over enduring construction. It’s a proposal of stunning modesty, suggesting a radically low-tech, inclusive and sustainable approach to the future. It is inspiring, but at the same time disorienting. It dissolves the time-is-money-approach to development and construction. Referring to the winner, juror Patricia Patkau declared, “The [In]Closure forest isn’t of the moment; it’s measured in decades and centuries—an important measure of ourselves.”

Some key historic and physical features of the site might have suggested a different jury conclusion—more development in tune with what is occurring in the surrounding environment. The competition site is surrounded by construction cranes, projects for large private owners that include the Gates Foundation and Paul Allen’s Vulcan, Inc. But Urban Interventions jury members seemed to be unmoved by the signs of booming redevelopment around them. Instead, In-Closure seems to suggest that our recession is truly never-ending.

There was only one submittal among the three finalists—Park, by Los Angeles-based KoningEisenberg Architecture + ARUP—that has the makings of a very credible (and relatively expensive) design concept for the site at hand, complete with playfield, transit center for an extended monorail. It also includes a tamer version of an urban forest.

Like [In]Closure, a third finalist, Seattle Jelly Bean, by a Boston Group called PRAUD, is provocative and exploratory—but in a widely divergent way. With an iconic tethered cloud of a structure, the Seattle Jelly Bean and “pods” on the ground are technically feasible and at the same time wildly futuristic. In the spirit of the 1962 World’s Fair, PRAUD has made a bid for the celebration of Seattle’s tech-heavy culture and economy.

There are several aspects of both Park and Seattle Jelly Bean that reflect a multi-disciplinary trend toward blending ground plane with architecture. Here we see combinations of grading, bridging and superstructures that provide sheltered passages and developable space underneath, and new prospects on top for viewing the city. This trend meshes well with green roof technology, and echoes Seattle’s very successful Olympic Sculpture Park, with its structural topography.

Urban Interventions was designed with the help of urban planner and former Van Alen Institute head, Ray Gastil, now on the faculty of Penn State. While finalists were hosted in Seattle and expected to draw from the site and it’s physical and historic context, submitters and jury were expected to focus above all on certain overarching themes, including “build an ecologically resilient city,” “renew the cultural campus,” and “generate dialog,” according to Gastil.

True to the stated intent of Urban Interventions, there is plenty of discussion to be derived from [In]Closure]: How can we plan for inclusiveness in making a city and lower the barriers to participation in development? How does public space get defined and used?

[In]Closure is about orchestrating chaos, giving new space over to diversity and small-scale entrepreneurship. It could be part of a vision for economic development in a no-growth or post-growth era. Because of the suggestion that it can be tweaked organically as it develops, [In]Closure itself can be said to be an ongoing conversation.

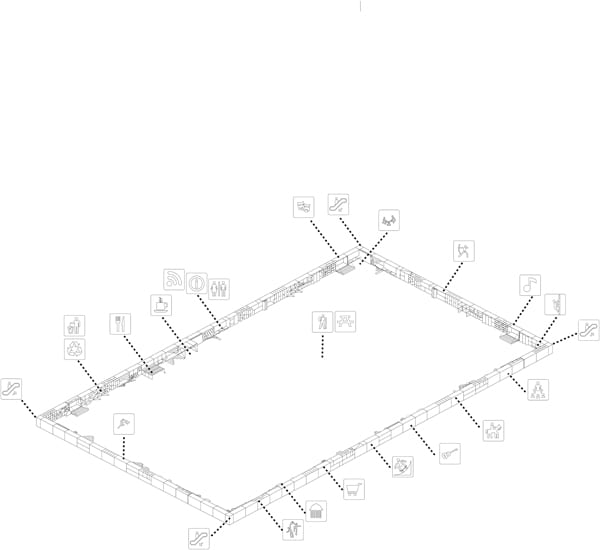

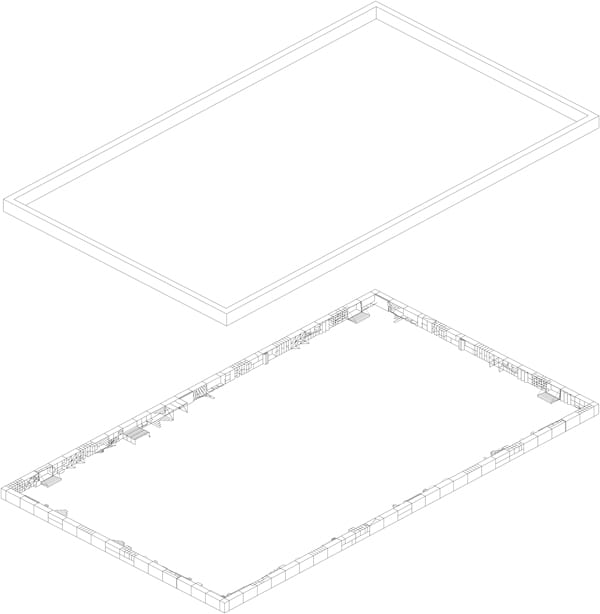

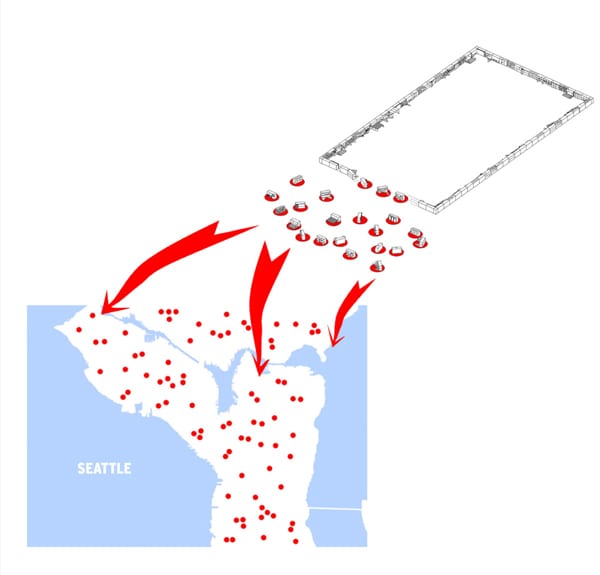

[In]Closure

ABF, Paris

[In]Closure is an idea that does not require large funding or any permanent and fixed edifice. It spreads ownership and control of public space among many different constituent groups. As an idea for a built environment, could work on many sites, and it contains the seeds of its own dissolution.

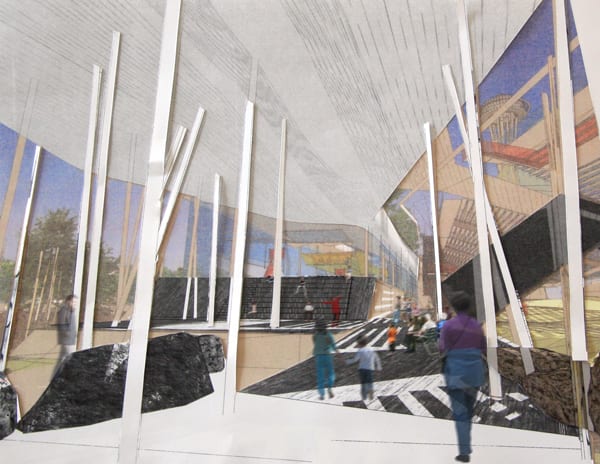

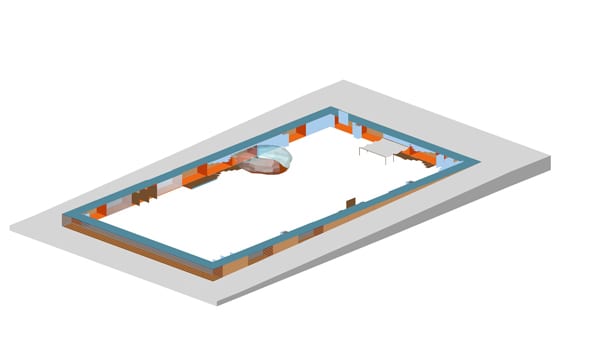

Many individual box-like structural units are linked together, each with its own use and program, designed and constructed according to certain critical dimensions. The boxes are on the scale of cargo containers, because they are built offsite and trucked in to pre-determined positions. Later, they can be removed from the site and permitted to live on in other settings. They are placed and linked, delinked and re-placed over time, all while surrounding a growing urban forest.

On the Seattle Center site, [In]Closure appears as a kind of inside-out street, a porous boundary with active frontage and rights-of-way on both sides. The trees and other forest species inside the rectangular perimeter are sponsored and planted over time by individuals and groups.

In a video shown by the team, the boxes seem to work like food trucks or market stalls, containing everything from small libraries and museums to merchandise to kitchens and freestanding furnishings. They open up on a daily basis to the outside, each commanding its own segment of the perimeter with vending areas, lighting, seating and deployable canopies or signage.

The idea hinges on a system of critical dimensions and perhaps agreed-upon values, but the economic barriers for participation are low and the possibilities for wide and diverse participation are high.

With “low cost” and “high social value,” [In]Closure “puts humans in the middle of the process,” according to team member Etienne Feher.

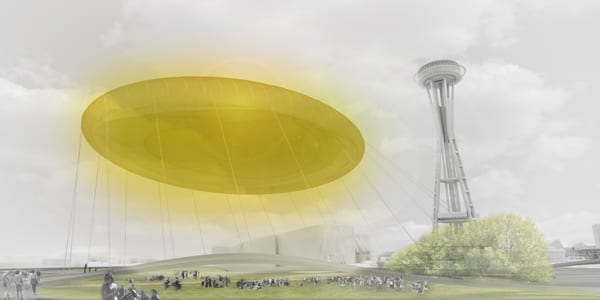

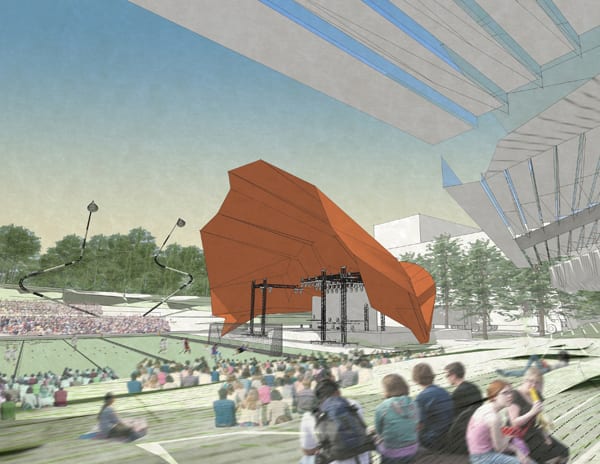

Seattle Jelly Bean

PRAUD, Boston

Rafael Luna, architect, PRAUD Dongwoo Yim, architect, PRAUD Cheng-Yang Lee, architect, Machado & Silvetti Associates

The PRAUD team was inspired by the day-to-day crowd-gathering success of the International Fountain, which has emerged over the decades since the fair as the heart of the Seattle Center landscape. It is arguably the most active and popular constructed landscape element—water-based or otherwise—anywhere in the city. After a very successful and technologically sophisticated upgrade in the 1990s, the fountain dances in its broad, inviting bowl to a changing program of music, with lots of children and adults watching and dancing along.

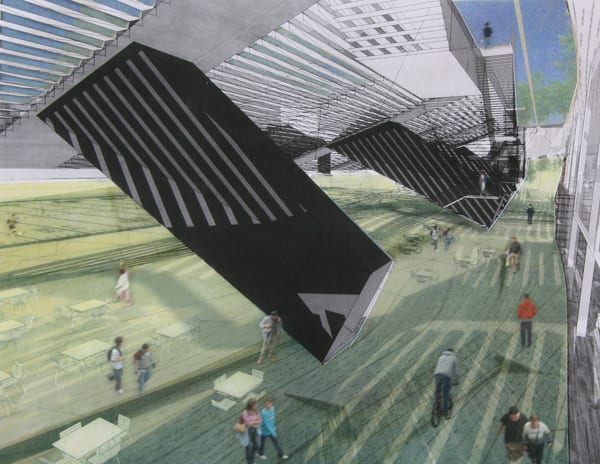

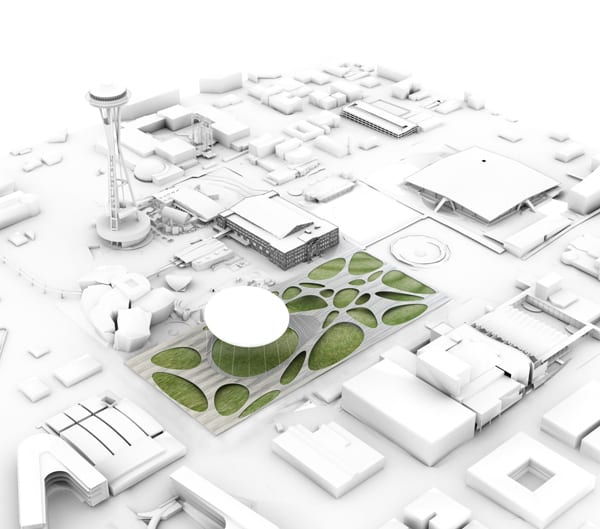

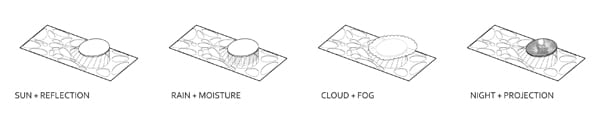

The Seattle Jelly Bean would provide another technology-driven focal point for crowds, visible from a much wider area but not quite competing with the Space Needle. The Jelly Bean itself is a kind of fixed, low-floating spacecraft. An instant landmark, it would also reflect our place-less connections through the internet, providing a giant screen on its underbelly for gaming and other types of real-time interactions, presumably vetted by the appropriate parent controls at Seattle Center.

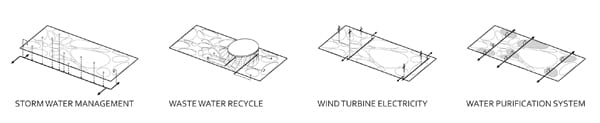

It is the stuff of science fiction. But it’s also perfectly feasible in the sense that the technologies involved—for solar collection, intelligent skin, climate control (misting), construction and positioning overhead—have all been tried and proven in some application. Members of the Boston-based team were mentored by Sheila Kennedy, an architect and MIT professor specializing in intelligent materials and systems in design.

The idea of the pods—organically shaped open spaces set into a ground-based superstructure beneath and around the jelly bean—is also based on the International Fountain. The idea is that the space underneath the rims of the superstructure can contain public facilities and sheltered amenities of different kinds. This is somewhat similar to the Aberdeen City Garden Competition’s winning design by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, where a similar perforated skin system provided multiple viewing possibilities for strolling visitors.

The biggest field is right underneath the Jelly Bean, according to PRAUD team member Dongwoo Yin. “(The Jelly Bean) projects the feeling that something is going to happen.”

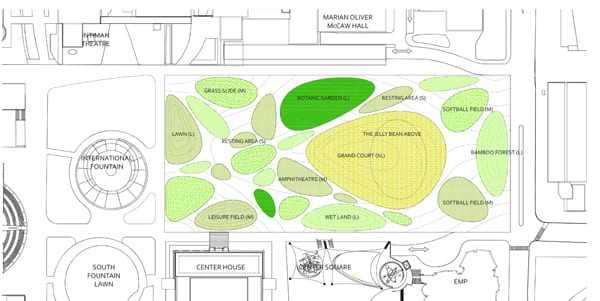

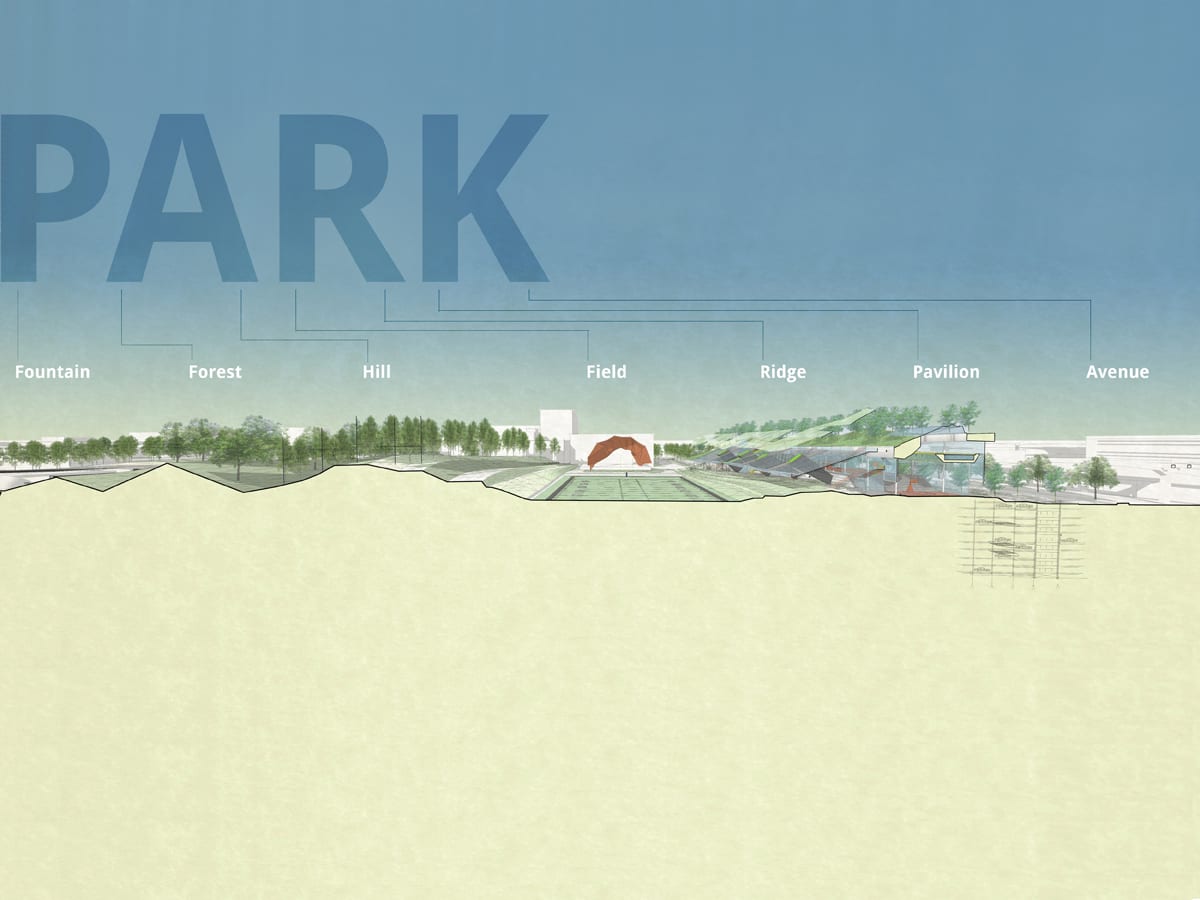

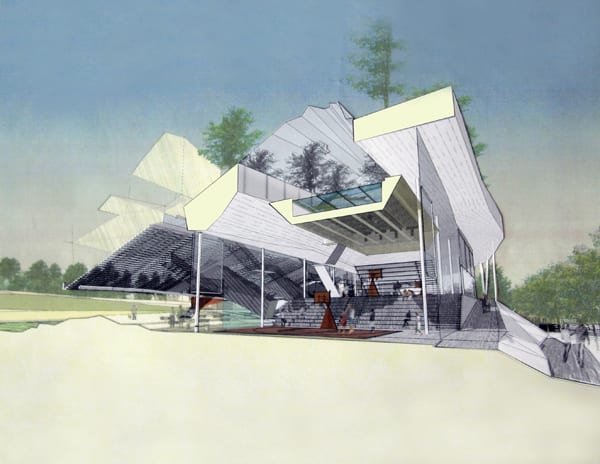

Park

KoningEizenburg Architecture + ARUP, Los Angeles

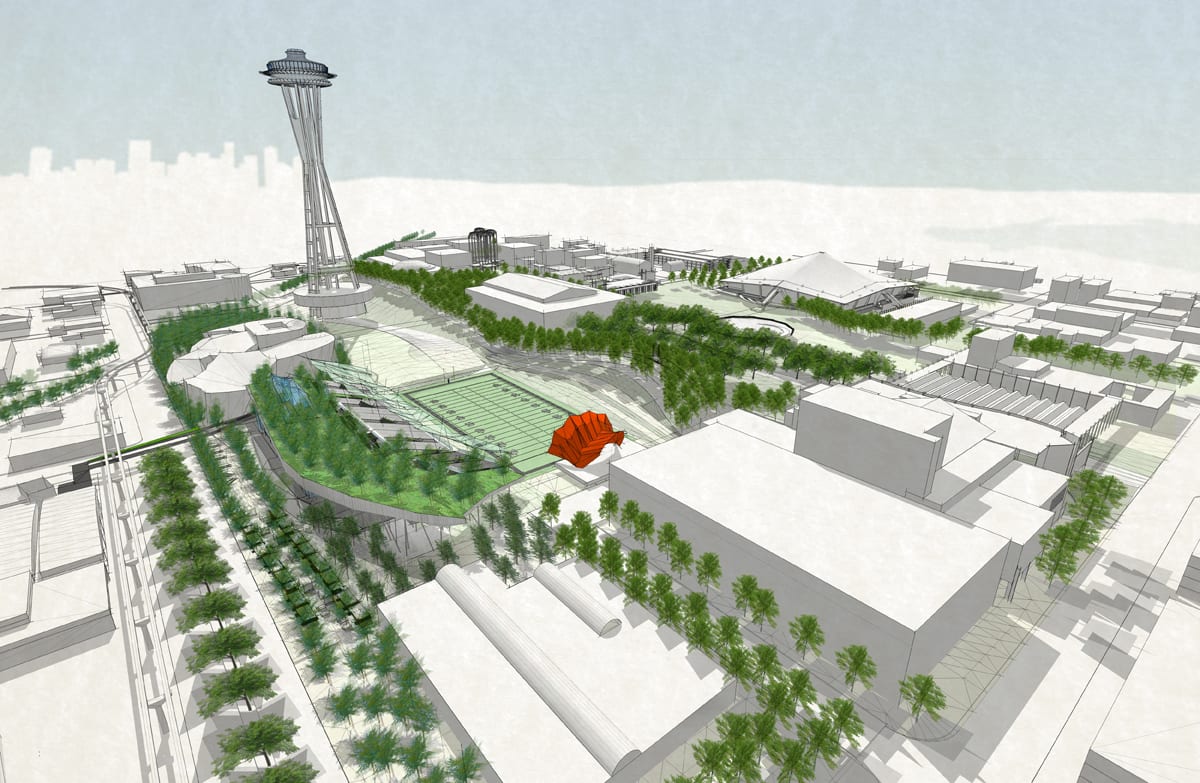

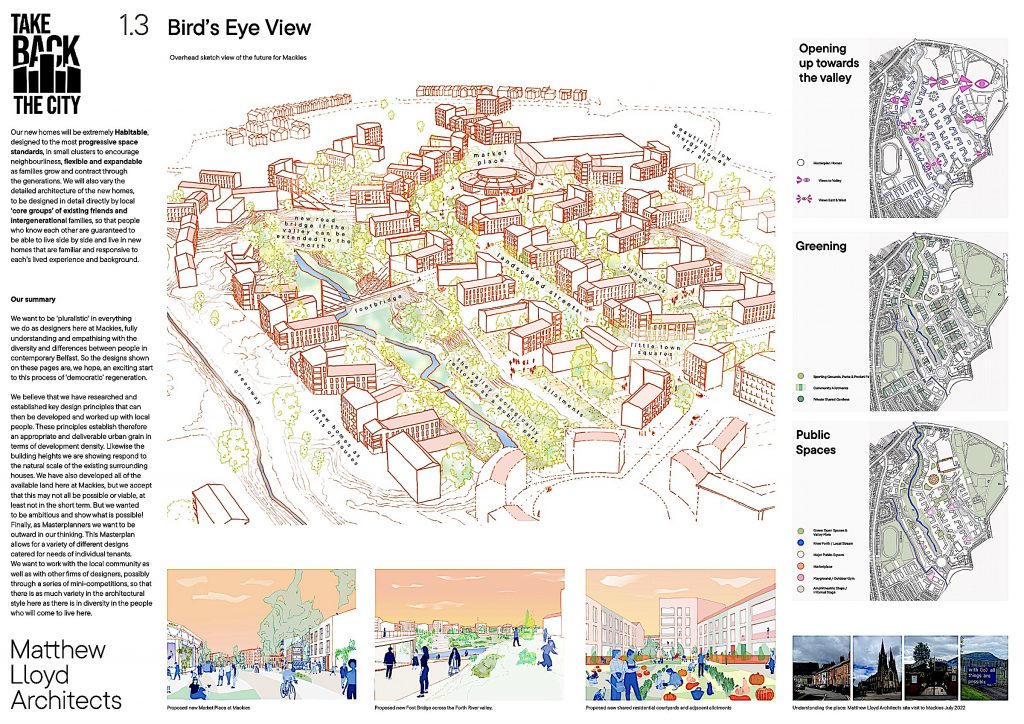

Park stands apart in that it is the only proposal among three finalists pointing directly toward an existing program for the plan area, including a playfield and generous open parkland. As such, it pays respect to historic planning efforts and public conversations around Seattle Center.

Its stated intention is to rebalance local and tourist use, interlacing everyday activities with special events and “replacing the patchwork of varied but disconnected interests” with a “seamless fabric.” It proposes an intense concentration of public uses, along with strategies for multiple connections, from view corridors to transit.

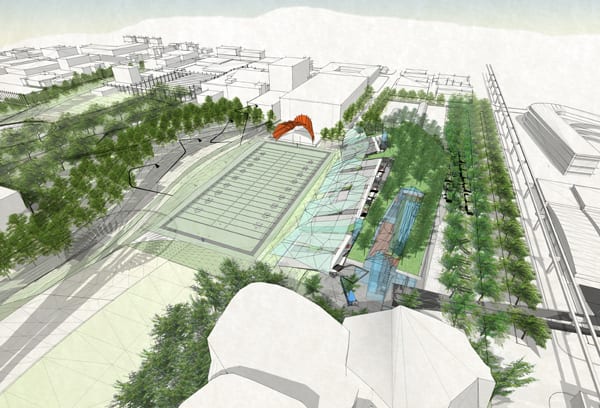

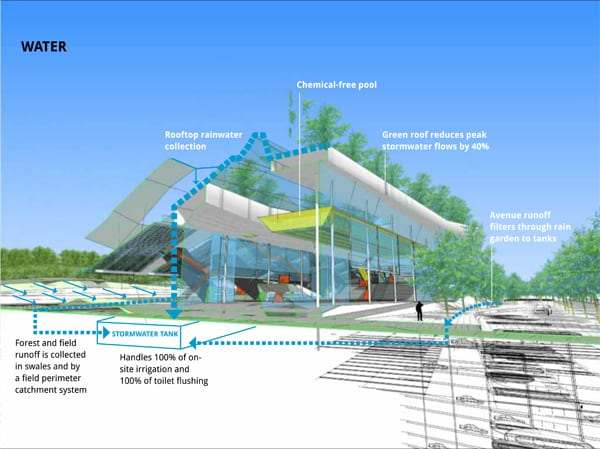

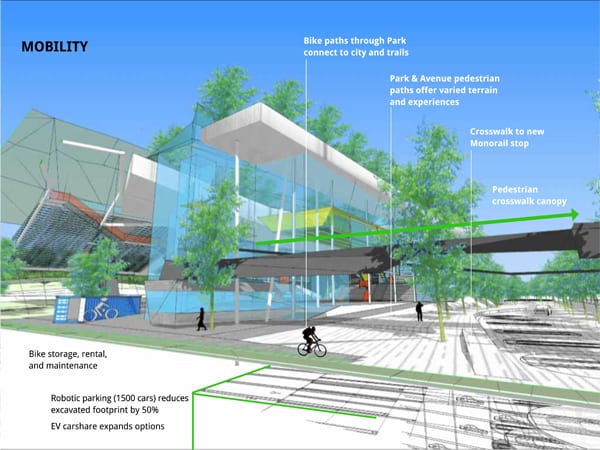

The east-west oriented rectilinear site is divided into roughly four north-south zones, with the playfield turned 90 degrees from its current position and served by a ridge with a grandstand near the top of its slope. Along busy and increasingly important 5th Avenue, an indoor public recreation facility with sports courts and pool lies adjacent to a “mobility hub” that would connect pedestrians—along with electric and human-powered wheeled vehicles—with the monorail. Robotic parking is tucked underneath the transit area, an automated vehicle storage system that reduces the structured parking footprint and price.

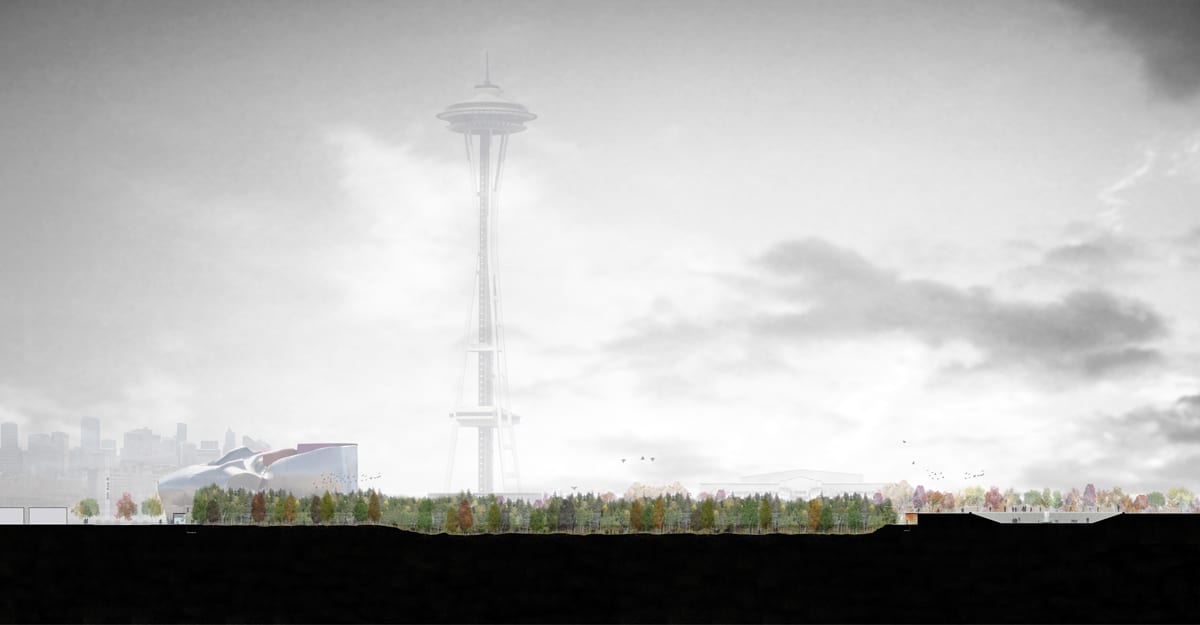

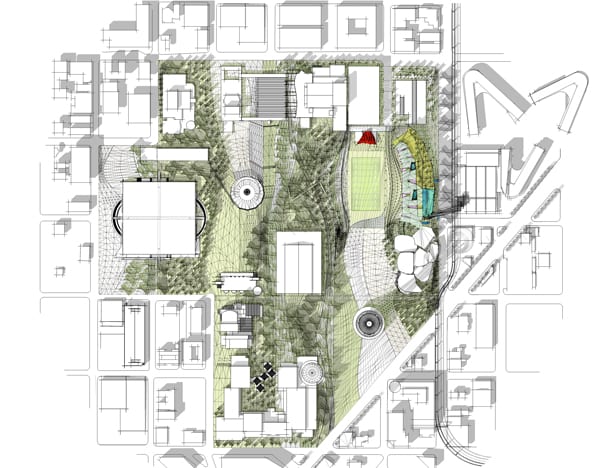

Like the ABF entry, the landscape parti is an urban forest. Laced with a trail network on one side of the playfield, the forest crops up again on a ridge on the opposite side of the field, and is echoed once in a green roof over the recreation pavilion and mobility hub superstructure. The plan includes a sweeping green with open views to the Space Needle, tying Park in with the Seattle Center context in a uniquely convincing way.

“(Today’s Seattle Center) doesn’t really operate like part of a city,” said Nathan Bishop, a member of the KoningEisenberg team. The elements of Park, he said, would actually serve the city by “unburdening existing infrastructure.”