A Famous Name Attracts 674 Entries

Winning entry by Sini Rahikainen, Hannele Cederström, Inka Norros, Kirsti Paloheimo, Maria Kleimola Images courtesy ©Alvar Aalto Foundation

Extensions to buildings are normally regarded as significant projects by most architects, whereas linking two existing structures might appear as a lesser priority. On rare occasion of

Read more…

SMAR Architecture Prevails in Final Round in Lithuania

Image: ©SMAR Architecture Studio

After several near misses in some recent high profile competitions, Aalto Museum, Guggenheim Museum, Lima Museum of Contemporary Art, SMAR Architecture Studio (Madrid/Western Australia) was rewarded with the commission for the Science Island project in Kuanas, Lithuania. Against

Read more…

The Museum as Sculpture Park

by Scott Cantrell, Kansas City Star Architecture Critic

[caption id="attachment_18206" align="alignnone" width="600"]  View of Steven Holl’s completed Museum addition from Museum garden – Photo: ©Stanley Collyer (2007) View of Steven Holl’s completed Museum addition from Museum garden – Photo: ©Stanley Collyer (2007)[/caption]

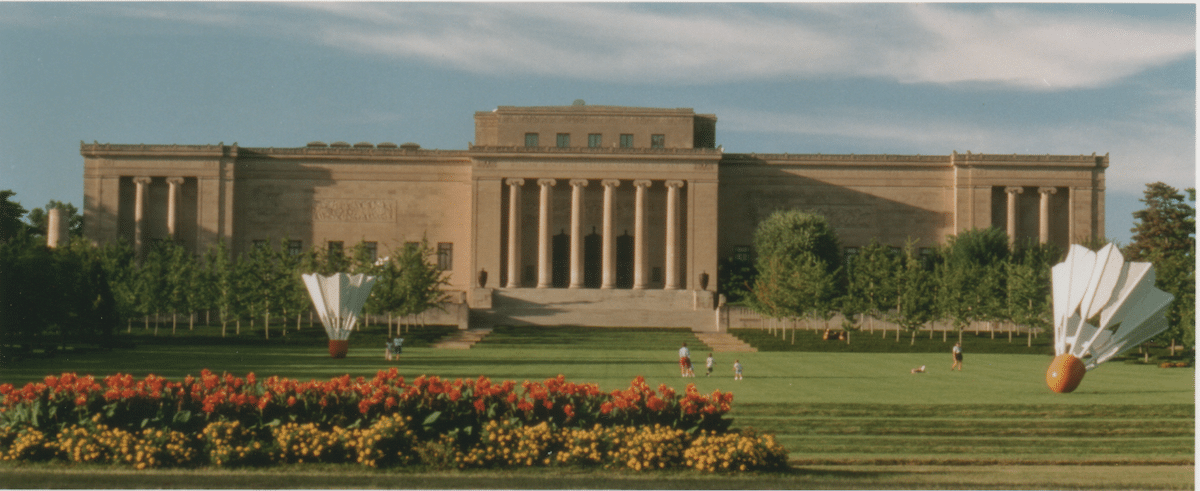

Fresh from his much-admired contemporary art museum Kiasma in Helsinki, Steven Holl has landed yet another important museum commission: an $80 million enlargemennt and renovation of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. The New York-based architect, whose choice was announced in July (1999), was one of six high-profile finalists picked to participate in a sketchbook competition. The others were Tadao Ando Architects and Associates, Annette Gigon/Mike Guyer, Carlos Jimenez Studio, Machado and Silvetti Associates, Inc., and Atelier Christian de Portzamparc.

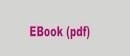

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art – Architect: Wight & Wight (1933) Photo: ©E.G. Schempf

The Nelson-Atkins museum is known especially for it collection of Asian art and furnishings. It also is developing an increasingly important collection of 20th-century, including a large group of Henry Moore’s and four large “Shuttlecocks” by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. The building program calls for a roughly 55 percent addition to the roughly 234,000 GSF of the museum’s 66-year-old existing structure, a stern neoclassical monolith designed by the Kansas City firm of Wight & Wight. (Other Wight & Wight landmarks in Kansas City include the deco-neoclassical City Hall and Jackson County Court House downtown.)

In a way, Holl’s design—with underground galleries topped by a series of seven free-form, translucent glass “lenses”—is the most conservative (entry) in that it presents the least obstruction to the 1933 building. Holl’s plan calls for a new main entrance lobby off the northeast corner of the present building, to be accessible from either ground level or a new underground parking garage. New galleries will be arrayed in an underground procession down the sloping east side of the Museum’s grounds. The above-ground lenses will house the entrance lobby, a cafe, an educational facility and library.

Read more…

by Miguel Ruano

Aerial view of Prado (left); site outline (right)

In October 1993, rainwater was seen filtering down through the cracked, poorly maintained roof of the Prado museum’s 18th century building, directly threatening some of the world’s greatest masterpieces, including Velazquez’s “Las Meninas.” Alarm bells went off, both in the building and in the media, and the public learned what until then only a few insiders knew: that one of the best and most famous museums in the world had been in desperate need of repair and expansion for decades. As an emergency solution, seven architects were requested in 1994 by the Ministry of Culture to submit their own ideas for the refurbishment of the museum’s roof. At the same time, the notion of a more ambitious, high-profile international competition to design an extension to the Prado began to take shape.

The competition was to be organized by the Ministry of Culture of Spain, with the technical assistance of the UIA (International Union of Architects) and UNESCO’s endorsement. With government elections coming up, the politicians in charge of the problem needed to demonstrate that the Prado was a high priority.. Thus, the media was immediately informed to ensure complete and regular coverage. From the start, the competition took on the character of a political public relations affair, which in the end, would come back to haunt them.

The Rules

The Prado Competition began in earnest in February 1995, when the Museum’s board of trustees approved the competition rules, which were in turn accepted by the Ministry of Culture of the ruling Socialist Party. In theory, there had been a top-level agreement on the approach to be taken to address the museum’s problems between the Socialist government and the main opposition party, the Conservatives, who by then were already expected to prevail in the next election. The reason for such agreement was obvious—to make sure that the process would not be overturned for political reasons.

Subsequently, it would appear that this agreement had been on a shaky foundation from the very beginning. According to the rules, which were fraught with ambiguities and inconsistencies, the Prado was going to double its size to 40,000 m2 by the year 2000 via its expansion into three adjacent buildings. This brought about the first conflicts, as some of the owners of the buildings in question denied any association with the expansion plans. This included Spain’s Catholic church, which took the Ministry to court. Madrid’s City hall, already under Conservative Party control before the elections, hardly appreciated such a high-profile initiative taken by the lame-duck Socialist government—directed at the very heart of the city. Moreover, at the insistence of the Museum’s Board of Trustees, a clause declaring that the “current architectural image of the main building could not be disturbed” had to be included in the rules (and it was). The original competition schedule had to be delayed two months, and last-minute, but significant, amendments had to be made to the rules, giving everyone a feeling of improvisation. The whole venture started on a note of controversy.

The Entrants

According to the organizer’s estimates, 500 architects from all over the world were expected to register for the competition. Some were individually invited to enter, including Isozaki, Ando, Hollein, Wilford, Salmona, Macary, Pelli and Siza (who immediately declared he would not take part, and then was asked to become a member of the jury, to which he said no as well). Others, like Foster and Calatrava, both well-known to the Spanish general public, had already confirmed their interest, which raised everybody’s expectations after their much publicized showdown at the Reichstag competition in Berlin.

Finalist – Distinction (2)

Alberto Martinez/Beatriz Matos

Madrid, Spain

Second Place in First Round (11 votes)

This low-impact proposal creates a new urban space in front of the Prado’s historic building back elevation, which now acquires a new character as an urban facade. Below this platform, a new three-story underground structure houses the entrance hall, auditorium, cafeteria, library and storage areas. A transversal gap across the plaza brings natural light into the underground structure. From this, the building connects with a new adjacent structure, located on the old covent’s grounds, which houses the museum’s services (restoration workshops, offices, etc.) -MR

Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

As architects learned more about the competition’s details, skepticism and even open criticism heightened—from architectural circles as well as in the media. Some internationally famous names such as Ungers or Ando decided not to register, arguing either work overload or disagreement with the competition’s rules. The organizers, however, seemed to be satisfied with the fact that well-known architects like Foster, Moneo, Calatrava, Tusquets, Bohigas, Navarro, Eisenman or Benevolo had decided to enter, thus giving credibility to the initiative.

Interestingly enough, while the organization was obviously very forthcoming in disclosing names of high-profile participants, they would not supply a complete list of entrants, arguing that the competition was anonymous and, as a consequence, only overall registration statistics could be released.

Finalist – Distinction (2)

Jean-Paul Duerig and Philippe Rami

Zürich, Switzerland

Seventh place in stage 1 semi-final round (6 votes) – tied with E. Zoido

This blunt proposal attaches a new gray granite and red brick structure, 300m (1,000 feet) long, to the Prado’s rear facade to house the entrance hall, exhibition halls, auditorium, cafeteria and shops. The nearby convent becomes a four-story building for the library, the restoration workshops, and the museum’s services and offices, while the old building will be used exclusively for exhibitions. The whole museum complex (four existent buildings, plus the proposed structure) are linked by underground connectors. –MR

above

Aerial view of model

left and below

Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

Read more…

by Dan Madryga

Winning entry by Bjarke Ingels Group

Tirana, Albania might be the last place that many would associate with cutting edge architecture. The capital of a poor country still struggling to sweep away the lingering vestiges of the communist era, it is understandable that architecture and design have not always been a top priority. Yet in the face of the city’s struggles, Tirana is striving to reclaim and reshape its image and identity, and international design competitions are playing no small role in this movement. And while Tirana has yet to be associated with contemporary architecture, the implementation of these design competitions has introduced a handful of renowned architecture firms to the city with high hopes of bolstering the international image of Albania. In 2008, MVRDV won commission for a community master plan on Tirana Lake that will herald forward thinking, ecologically minded urban development. Earlier this year, Coop Himmelb(l)au won a competition for the new Albanian Parliament Building with a design intended to symbolize the transparency and openness of democracy. Most recently, Tirana can now add BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) of Denmark to these ranks as the winner of the New Mosque and Museum of Tirana & Religious Harmony Competition, an ambitious project aimed to further rekindle a tattered Albanian cultural identity.

The recent efforts to renew and improve the physical image of Tirana can be attributed in large part to the city’s three-term mayor, Edi Rama. With his background as an artist, Rama has launched a number of initiatives over his decade in office, intent on improving the aesthetic image of Tirana. The design competition for the mosque and cultural complex can be viewed as the latest component of his “Return to Identity” project, which has gone to great lengths to remove the many unsightly and illegally constructed buildings that plague the city and help provide a clean slate for more progressive architecture and urban design.

The Mosque and Museum competition focuses on reclaiming a key religious and cultural identity that was long suppressed by communism. While Albania claims three chief religions—a Muslim majority alongside significant Orthodox Christian and Catholic communities—a strict communist regime ruthlessly banned religion. For over four decades, Albanians were under the thumb of an atheist regime where religious practitioners could face humiliation, imprisonment, and even torture and execution. The anti-religious campaign reached its zenith in the 1960s, when most Mosques and churches were demolished, and a select few with architectural significance were converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, and youth centers.

The revival of religious institutions began with the 1990 collapse of the communist regime. Yet decades of suppression took their toll, with the vestiges of Albania’s religious heritage essentially reduced to rubble. While the two Christian religions have since regained centers of worship, after twenty-one years of restored religious freedom, Tirana still lacks a mosque suitable for serving the sizable Muslim population. Only one mosque still stands in the central city—the historic Et’hem Bey Mosque—certainly a potent symbol of Tirana’s Islamic heritage, but particularly inadequate in size to accommodate the large numbers who would want to worship there on special occasions.

Hence emphasis in the brief concerning the size of the building: a grand mosque that can adequately serve 1000 prayers on normal days, 5000 on Fridays, and up to 10,000 during holy feasts. Supporting this mosque, the program also specifies the design of a Center of Islamic Culture that will house teaching, learning, and research facilities including a library, multipurpose hall, and seminar classrooms.

Another component of the competition program, the Museum of Tirana and Religious Harmony, moves beyond the realm of the Muslim community in an explicit gesture to bring together citizens from all faiths and backgrounds. Aside from presenting the general history of Tirana, the museum will focus on the city’s religious heritage, highlighting both the turbulent moment of suppression under communism as well as the religious harmony that has since been reinstated. Educating the public about Islamic culture and promoting religious tolerance at a time when relations between religious communities are strained throughout the world is certainly a noble objective.

Underlining the importance of this project is its prominent site on Scanderbeg Square, the administrative and cultural center of Tirana where major government buildings share an expansive public space with museums and theaters. The square itself was the subject of a 2003 design competition that will eventually reclaim the urban center—at present a rather chaotic vehicular hub—as a pedestrian zone with a more human scale. Situated on triangular site adjacent to the Opera and Hotel Tirana, the Mosque and Cultural Center will be a highly visible component of Tirana’s urban landscape.

left: BIG site plan; right: rendering of Scanderbeg Square to appear after redesign (image by seARCH Architects)

The two-stage, international competition was organized by the City of Tirana and the Albanian Muslim community and advised by Nevat Sayin and Artan Hysa.

Over one hundred teams—the vast majority European—submitted qualifications for the first stage. In early March, the short-listing committee selected five teams to receive an honorarium of 45,000 Euros each to develop designs:

• Bjarke Ingels Group – Copenhagen, Denmark

• seARCH – Amsterdam, Holland

• Zaha Hadid Architects – London, UK

• Andreas Perea Ortega with NEXO – Madrid, Spain

• Architecture Studio – Paris, France

The designs were judged by a diverse European panel:

• Edi Rama – Mayor of Tirana, Albania

• Paul Boehm – architect, Cologne, Germany

• Vedran Mimica – Croatian architect; current director of the Berlage Institute

• Peter Swinnen – Partner and architect at 51N4E, Brussels

• Prof. Enzo Siviero – engineer; Professor at University IUAV, Venice

• Artan Shkreli – architect, Tirana, Albania

• Shyqyri Rreli – Muslim community representative

On 1 May 2011, the panel announced Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) as the winner.

Read more…

by Stanley Collyer

Photo: © Timothy Hursley (all other photos by author)

When you think of iconic libraries in the United States, Louis Kahn’s Kiimball Library in Fort Worth, Texas is one of the first that comes to mind. But space in the old existing Museum of Modern Art as well as in the Kahn building was limited; so in 1996 a competition was organized to select an architect, based on a winning design. The competition, which was documented in our quarterly (COMPETITIONS, Vol. 8,#1), was supplemented by an insightful article by the former Dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Texas at Arlington, George Wright. He mentioned that the competition took place at the same time that the competition was occurring for MOMA in New York, but that this did not deter architects from the first echelon from submitting their qualifications for a shortlist.

From that group, Tadao Ando from Japan won out over Richard Gluckman (New York), Arata Isozaki (Tokyo), Ricardo Legorreta (Mexico City), and David Schwartz (Dallas).

The brief stipulated that the new museum should “neither mimic the Kimball nor dispute its primacy.” As a very modern giant box with protruding galleries breaking up the façade by facing out into the lagoon, Ando’s design did neither. But its very spacious entrance and lobby area was an immediate sign that it was a different kind of museum. Consisting for the most part of large volumes, it was ideally designed to accommodate 21st Century art installations and art works.

Visiting such an important facility more than a decade after its opening was an opportunity to examine how the museum has stood the test of time. From my perspective, it is certainly one of the best museums dedicated solely to modern art that I have visited—a view affirmed by others accompanying me on this visit, most of whom were not architects but frequent museum visitors.

Aside from the many attributes of the main building, the landscaping, containing a large lagoon surrounding the structure, was also masterfully conceived. As a shallow element at the edge of the building, one could see an artwork by Jenny Holzer, illuminated words in red, carrying a message out of the building into the shallows. Also of special note, exemplifying the spatial attributes of the building, was Martin Puryear’s Ladder for Booker T. Washington (left), an obvious crowd favorite.

This building, exquisite in its finished concrete interior and spatial planning, with a flexibility to accommodate all kinds of modern art, is an example not only of good architecture in the broader sense, but also turning the landscape into an art form.

Martin Puryear – Ladder for Booker T. Washington

View to museum entrance

Main lobby

Lagoon perspective

Read more…

Image © SMAR Architecture Studio

Until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1989, the occupied Baltic countries were known for their hi-tech contributions to the Soviet economy. As a carryover from that period, the Baltic nations still emphasize technology as a major factor in their economies. Thus, the establishment of a new Science museum by Lithuania in the nation’s capital of Kaunas is hardly surprising. To highlight the importance of this project, the government turned to a design competition, providing the museum with international exposure and attracting the attention of the global architectural community.

The stated purpose of the new project was clear from the competition brief:

‘Science Island’s mission is to popularize science through hands-on enquiry and exposition and celebrate recent achievements in science and global technologies. The Centre, within the celebrated university city of Kaunas, one of UNESCO’s global creative cities, will focus particularly on environmental themes and ecosystems, demonstrating sustainability and future energy technologies in the design of its own building. The circa 13,000 sqm site for the development is ideally positioned in close proximity to Kaunas’ historic Centras district, and most of Lithuania’s nearly three million residents live under an hour’s drive away.’

Read more…

A Former Soviet Airstrip in the Service of Estonian Cultural History

In 2005 the Estonian government decided to stage an international competition as a means of selecting a design for a new National Estonian Museum. Since there was already a Museum of Estonian History in Tallinn, the capital, one might assume

Read more…

View of completed project Photo: ©Takuji Shimmura Winning team: Lina Ghotmeh, Dan Dorell, Tsuyoshi Tane

Architecture in the service of the state can be a powerful tool. It lets a faceless bureaucracy present itself as a real thing. It can make ideals and memories into concrete facts. And it is usually big. A recent competition for a new National Museum in the small country of Estonia shows the potential and pitfalls of such a national architecture. While it can define the state, what does that mean when the state as a concept is a difficult idea these days? Now that true power lies not only with multinationals, but also with trans-national organizations like the European Union, of which Estonia has been a member since 2004, what is the state? Moreover, what history does a country that was only independent between 1925 and 1941, and then again since 1991, really have as such? What future can it imagine for itself? What is there left for architecture to represent?

The answer, if we can believe the results of the recent Estonian National Museum Competition, whose winner was announced this spring, is that architecture can use place above all else for meaning. This means not just utilizing the site in terms of its geography and geology, but also looking at, preserving and focusing on the full range of uses to which that site has been put, as well as the larger implications –both physically and conceptually—that a site might have. Everything human beings have done with a place, everything they have built there, and every association they have with a site as part of a much larger whole is the basic material the architect can use to design a construction that will bring out all of this history and all of these latent associations. The winning design in this competition, “Memory Field,” submitted by a multinational group of architects Dan Dorell and Lina Ghotmeh from Paris, and Tsuyoshi Tane from London, certainly accomplished this expression of place with a clear and simple proposal.

The site for the Estonian National Museum is not, as one might expect, in Estonia’s charming capital, Tallinn, but in the second largest city, Tartu. Located a few hours to the East of the seaside capital, almost on the border with Russia, Tartu is an industrial and trading node at the edge of the vast planes of pine forests and tundra that stretch from here to Siberia. It was on the outskirts of Tartu, in an 18th century manor house, that local agitators for defining a national identity by preserving local culture conceived the museum before there was even a country. In 1909 they began collecting “Finno-Ugric” (as the local population is called) artifacts and displaying them to show citizens that there were traditions of which they should be proud. Clothing, implements and especially lacework all showed the culture of a rapidly disappearing peasant population. Later, films documenting those peoples also joined the collections.

During the Second World War, the Museum moved to downtown Tartu, and it wasn’t until recently that the decision was made to reoccupy the former site. In the meantime, a large Russian airbase, now abandoned, took over much of the area, and its disused landing strip points directly at the site’s core, while the ruins of the military complex dwarf the remains of the former manor estate. A small lake provides a bucolic counterpoint to this rather bleak collection of artifacts. “This is the frozen edge of Europe,” says Winy Maas, who was part of the competition jury; “it is where you have a collection of incredible textiles dating back to the 14th century, but it will be housed on a site where wolves roam. You are really between worlds, and we thought the most important thing was to define that condition.”

Read more…

This is not what we fought for!

by Wilfried Wang*

Winning design: ©Herzog & de Meuron

Wilfried Wang’s commentary on the competition results for the extension of Mies’s Museum of the 20th Century (M20) was published in the German journal, Bauwelt (40.2016). The author is the founder of the Berlin architectural practice Hoidn Wang Partner with Barbara Hoidn and has been the O’Neil Ford Centennial Professor in Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin since 2002. The text, translated by the Editor, is a slightly modified version (by the author) that appeared in Bauwelt.

Both in architectural and urbanistic terms, the jury’s misguided selection of the Herzog de Meuron entry as the winner of the M20 competition is another missed opportunity for Berlin.

By extending the form of this introverted structure to cover the entire competition site, little or no value is added to the immediate environs. To the contrary, that and the immense surfaces of the facades, right up to the edge of the pedestrian walkways, only serve to diminish the importance of the surrounding buildings. All the trees to the south of the site will disappear, and 90% of the outer walls of the building, regardless of the suggested use of porous brick detailing, are completely closed off. Only the eastern entrance of the Herzog de Meuron plan faces the main entrance of Scharoun’s State Library; the other two main entrances lack any such connection with the urban context. Thus, the Cultural Forum gains nothing in urban quality, but rather the sense of desolation will increase.

The corridors stacked over one another, labeled “Boulevards” by the architects, are connected in the quadrants by smaller corridors and stairs. The metaphor, “Boulevard,” is as misleading as was Le Corbusier’s “rue intérieur.” Boulevards are accessible 24 hours a day as open public spaces. In the evenings these corridors will be closed to the public.

Rectangular exhibit areas are placed on three levels—not easily accessible to the visitor as a result of the labyrinth-like circulation plan. What is so innovative about this? The Goetz Pavilion was innovative.

Viewed from an artistic- and architecture-historic point of view, the selection of this design was an egregious mistake. First of all, a gable roof design is not appropriate for this Cultural Forum, and, secondly, it does not express the modern spirit; actually it is quite the opposite. Originally, the Cultural Forum was not only West Berlin’s gesture to the East, but also an attempt to replace the Nazi north-south axis with a modern alternative.

The lack of sensitivity, unnecessary haste followed by yearlong inaction and a desire for label-architecture have strangely culminated in a provincial selection. The shortlisted designs from the initial open competition were more modern, sensitive, and led one to assume that a different solution would be in store.

If this design were actually to be built, this unfortunate selection process would result in a catastrophe. This reminds me of the competition for the City of Culture for Santiago de Compostela. In that instance I was the sole juror to vote against the Eisenman scheme. Then my arguments fell on deaf ears. I was not a juror in the M20 competition. For this reason, I’m thankful that I can air my concerns about this result; however, I believe that my concerns will once again suffer the same fate. -WW

*The following should be pointed out: For his Master’s degree in 1981, the author researched six cultural centers—amongst others, London’s South Bank Centre, Paris’ Centre Beaubourg and Berlin’s Kulturforum. In 1992 the author published a monograph on the work of HdM. The author was a member of the jury for the limited competition for the extension of the Basel Kunstmuseum, which was unanimously awarded to Gigon & Guyer; HdM was one of the five invited architects. In 2013 the author published a monograph on Scharoun’s Philharmonie, therein his essay on “The Lightness of Democracy.” As part of his activities in the Architecture Section of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, the author was co-organizer of a number of public discussions on the development of the Kulturforum, in which politicians and representatives of the Prussian Cultural Foundation (the users of M20) participated. In 2014 and 2015 the author set the design of M20 as a test for advanced design studios. Finally, the competition entry for the first phase of the M20 selection process by the author’s office was eliminated in the first round: www.hoidnwang.de/04projekte_53_de.html.

View of site from Mies van der Rohe’s Museum of the 20th Century to Hans Sharoun’s Berlin Philharmonic

Photo: Stanley Collyer

The above photo of the M20 site makes abundantly clear the difficult challenges facing the architects who tried to produce an acceptable solution for the extension of the Mies museum. One might normally assume that a grand plaza would have been an appropriate answer. However, an extension of the M20 came into the conversation when a major art collector offered the collection to the museum in its enirety—necessitating more exhibit space.So the solution to this expansion had to lie in a design competition.

First of all, the very presence of two easily recognized architectural icons facing each other across the site would normally be enough to intimidate anyone. So the initial question in the back of everyone’s mind would have been: should this addition simply constitute a link between the two buildings; or should it be something more?

Organized in two stages, the first, anonymous stage was open internationally and resulted in eight finalist entries advancing to a second stage (http://competitions.org/2016/02/berlins-20th-century-art-museum-competition/?preview_id=18468&preview_nonce=20af7e537d&_thumbnail_id=-1&preview=true). From the 480 competition entries, one would have assumed that at least one entry would have been convincing enough to gain favor not only from the jury, but also the community. The addition of this second stage was to accommodate short-listed name firms, so there could be no complaints that high-profile, established architects were not part of the mix. Based on the final rankings from the second stage, none of the premiated designs really solved this challenge satisfactorily. Most tried to recognize the importance of a sightline between the two icons by going at least partially underground.

Site diagram

The two firms that took this most to heart were both from Japan—SANAA and, no surprise, Sou Fujimoto, with the latter covering the entire partially submerged structure with vegetation. The second-place winner from Denmark found favor from the main client with what looked to be very commercially looking solution, what one might imagine as an outdoor shopping center. The most extreme anti-urbanistic example honored by the jury with a merit award was OMA’s pyramid-like scheme, completely blocking any relationship between Mies and Sharoun by inserting their own icon in between the two.

When Herzog & de Meuron’s design was declared the winner, it had to come as somewhat of a surprise. Structurally no more than a shed in appearance, it seemed to be completely out of character with all of its neighbors—almost thumbing its nose at them. The abundant use of brick, its blank facade facing the street, and the claim by the authors that the corridor cut through the middle as a “boulevard” would serve as a symbolic link between the Museum and Philharmonie, was hardly convincing. This is especially true when one realizes that it would be closed off evenings to all comers. As an urbanistic solution and example of architectural expression, the winner unfortunately fell flat on its face. -Ed

Read more…

|

Helsinki Central Library, by ALA Architects (2012-2018)

The world has experienced a limited number of open competitions over the past three decades, but even with diminishing numbers, some stand out among projects in their categories that can’t be ignored for the high quality and degree of creativity they revealed. Included among those are several invited competitions that were extraordinary in their efforts to explore new avenues of institutional and museum design. Some might ask why the Vietnam Memorial is not mentioned here. Only included in our list are competitions that were covered by us, beginning in 1990 with COMPETITIONS magazine to the present day. As for what category a project under construction (Science Island), might belong to or fundraising still in progress (San Jose’s Urban Confluence or the Cold War Memorial competition, Wisconsin), we would classify the former as “built” and wait and see what happens with the latter—keeping our fingers crossed for a positive outcome.

Read More…

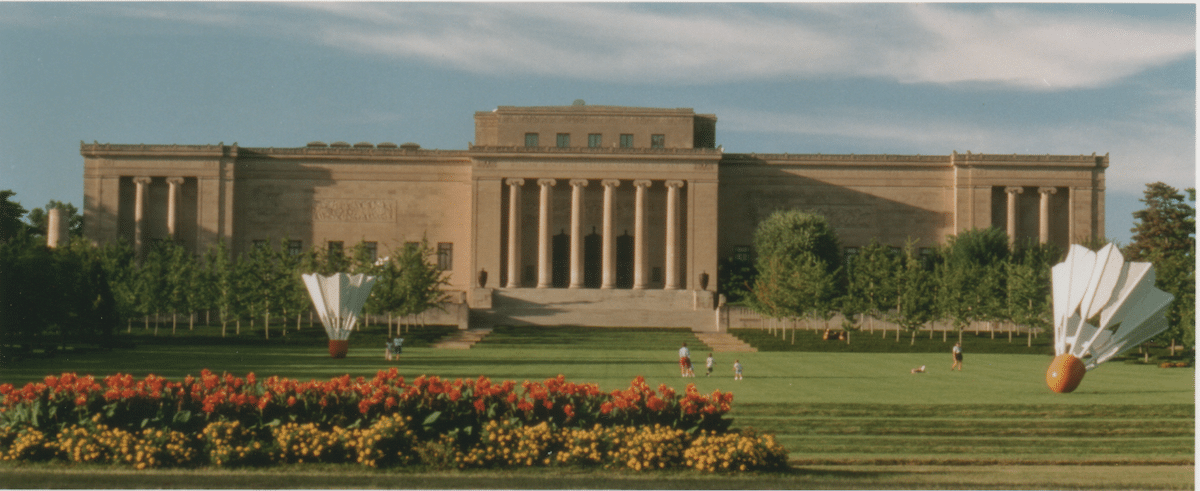

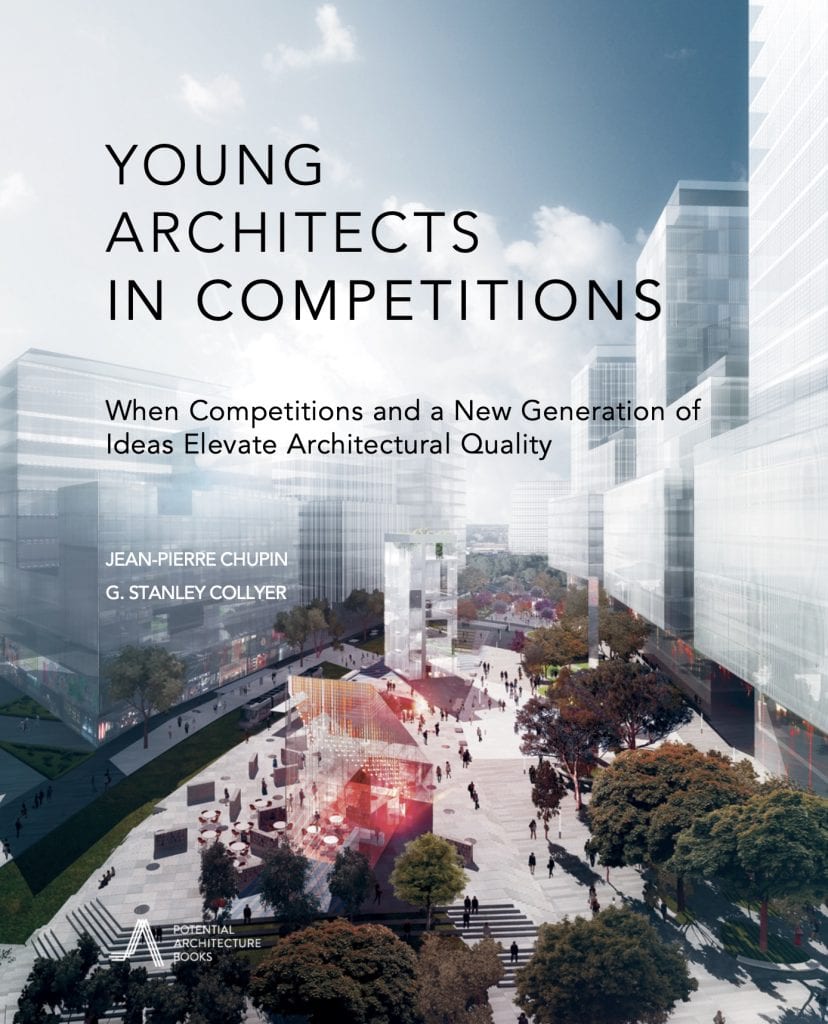

Young Architects in Competitions

When Competitions and a New Generation of Ideas Elevate Architectural Quality

by Jean-Pierre Chupin and G. Stanley Collyer

published by Potential Architecture Books, Montreal, Canada 2020

271 illustrations in color and black & white

Available in PDF and eBook formats

ISBN 9781988962047

What do the Vietnam Memorial, the St. Louis Arch, and the Sydney Opera House have in common? These world renowned landmarks were all designed by architects under the age of 40, and in each case they were selected through open competitions. At their best, design competitions can provide a singular opportunity for young and unknown architects to make their mark on the built environment and launch productive, fruitful careers. But what happens when design competitions are engineered to favor the established and experienced practitioners from the very outset?

This comprehensive new book written by Jean-Pierre Chupin (Canadian Competitions Catalogue) and Stanley Collyer (COMPETITIONS) highlights for the crucial role competitions have played in fostering the careers of young architects, and makes an argument against the trend of invited competitions and RFQs. The authors take an in-depth look at past competitions won by young architects and planners, and survey the state of competitions through the world on a region by region basis. The end result is a compelling argument for an inclusive approach to conducting international design competitions.

Download Young Architects in Competitions for free at the following link:

https://crc.umontreal.ca/en/publications-libre-acces/

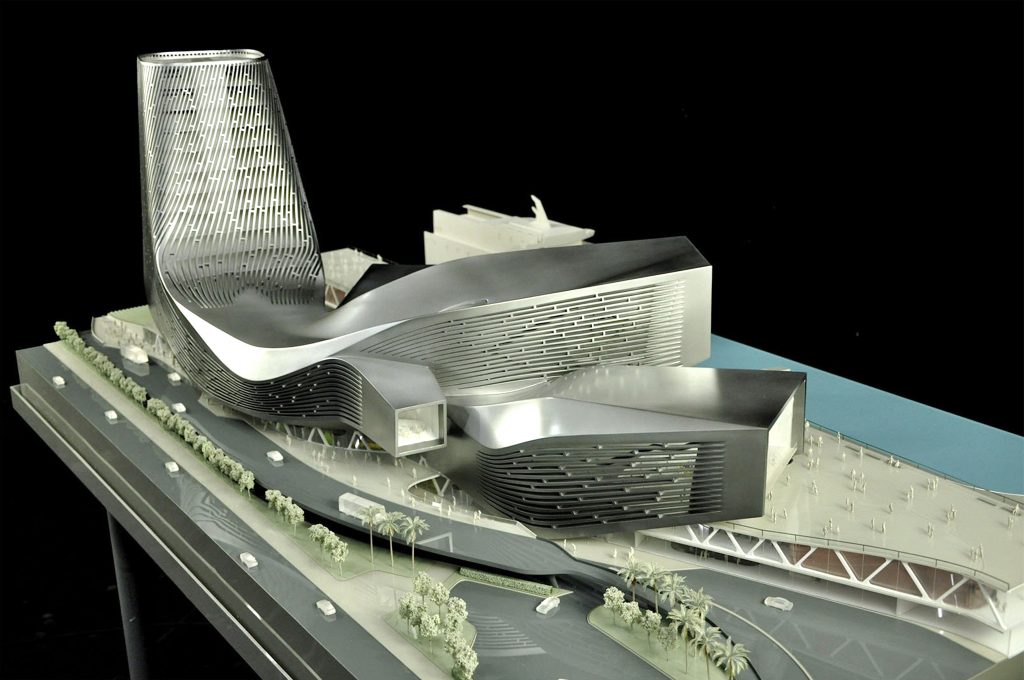

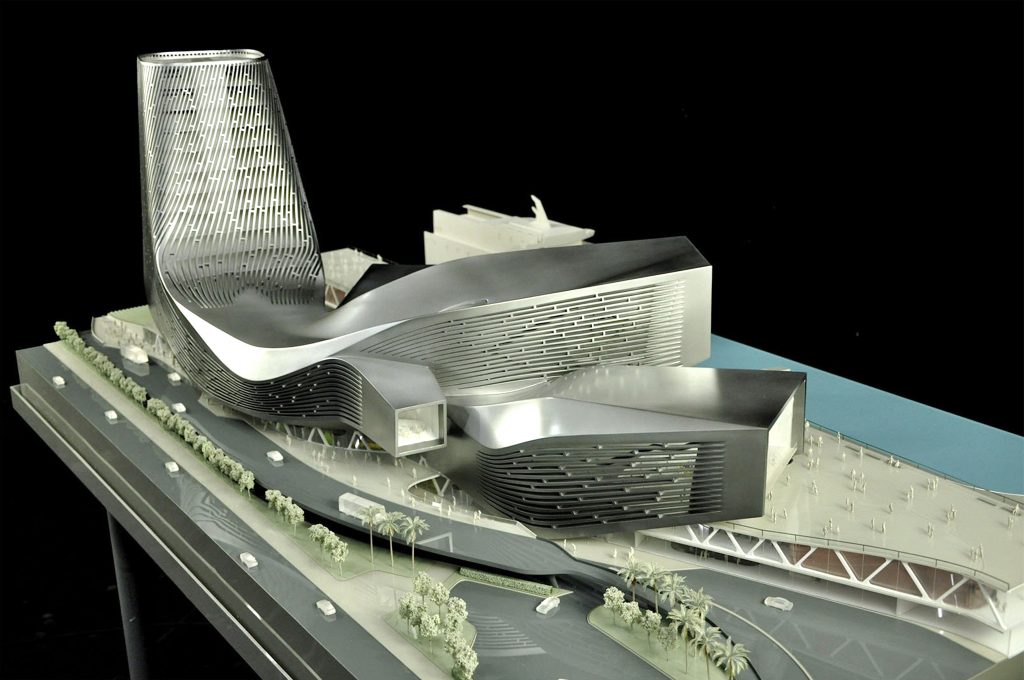

RUR model perspective – ©RUR

New Kaohsiung Port and Cruise Terminal, Taiwan (2011-2020)

Reiser+Umemoto RUR Architecture PC/ Jesse Reiser – U.S.A.

with

Fei & Cheng Associates/Philip T.C. Fei –R.O.C. (Tendener)

This was probably the last international open competition result that was built in Taiwan. A later competition for the Keelung Harbor Service Building Competition, won by Neil Denari of the U.S., the result of a shortlisting procedure, was not built. The fact that the project by RUR was eventually completed—the result of the RUR/Fei & Cheng’s winning entry there—certainly goes back to the collaborative role of those to firms in winning the 2008 Taipei Pop Music Center competition, a collaboration that should not be underestimated in setting the stage for this competition.

Read more…

Winning entry ©Herzog de Meuron

In visiting any museum, one might wonder what important works of art are out of view in storage, possibly not considered high profile enough to see the light of day? In Korea, an answer to this question is in the making.

It can come as no surprise that museums are running out of storage space. This is not just the case with long established “western” museums, but elsewhere throughout the world as well. In Seoul, South Korea, such an issue has been addressed by planning for a new kind of storage facility, the Seouipul Open Storage Museum. The new institution will house artworks and artifacts of three major museums in Seoul: the Seoul Museum of Modern Art, the Seoul Museum of History, and the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

Read more…

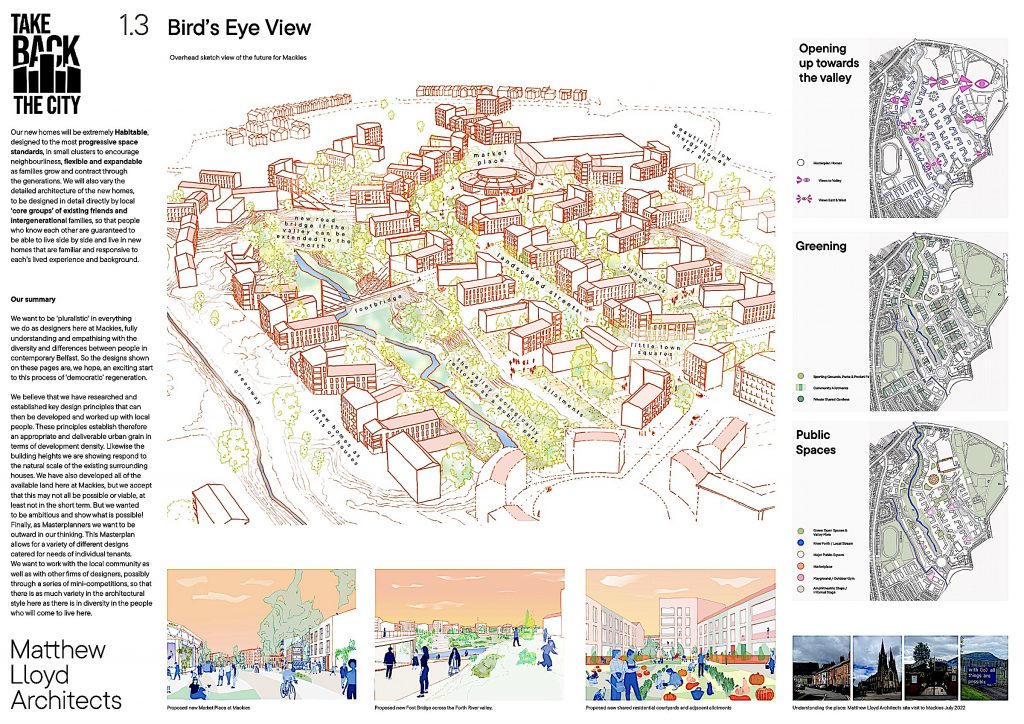

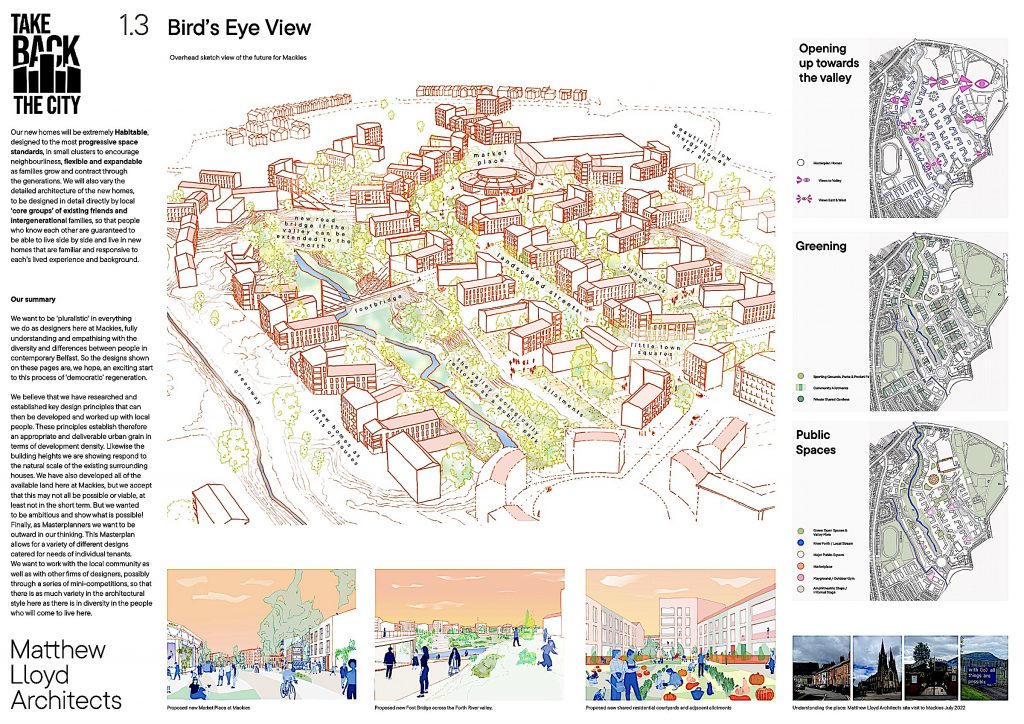

Belfast Looks Toward an Equitable and Sustainable Housing Model

Birdseye view of Mackie site ©Matthew Lloyd Architects

If one were to look for a theme that is common to most affordable housing models, public access has been based primarily on income, or to be more precise, the very lack of it. Here it is no different, with Belfast’s homeless problem posing a major concern. But the competition also hopes to address another of Belfast’s decades-long issues—its religious divide. There is an underlying assumption here that religion will play no part in a selection process. The competition’s local sponsor was “Take Back the City,” its membership consisting mainly of social advocates. In setting priorities for the housing model, the group interviewed potential future dwellers as well as stakeholders to determine the nature of this model. Among those actions taken was the “photo- mapping of available land in Belfast, which could be used to tackle the housing crisis. Since 2020, (the group) hosted seminars that brought together international experts and homeless people with the goal of finding solutions. Surveys and workshops involving local people, housing associations and council duty-bearers have explored the potential of the Mackie’s site.” This research was the basis for the competition launched in 2022.

Read more…

Alster Swimming Pool after restoration (2023)

Linking Two Competitions with Three Modernist Projects

Hardly a week goes by without the news of another architectural icon being threatened with demolition. A modernist swimming pool in Hamburg, Germany belonged in this category, even though the concrete shell roof had been placed under landmark status. When the possibility of being replaced by a high-rise building, it came to the notice of architects at von Gerkan Marg Partners (gmp), who in collaboration with schlaich bergermann partner (sbp), developed a feasibility study that became the basis for the decision to retain and refurbish the building.

Read more…

|