A Final Building Block for the Taichung Cultural Center

Night view of tower ©Elizabeth de Portzamparc

Everyone is well aware of the measures one encounters when entering almost any tower, residential or office, in this era of high security. We are not just talking about protecting the occupants of a residential

Read more…

with Stanley Collyer

Bundeskanzleramt Berlin Competition (1996); Completion (2000) Photo: courtesy Schultes Frank Architekten

COMPETITIONS: In our last conversation, we talked about the whole issue of Berlin’s identity and what approach one should use in reconstructing the urban fabric between East and West—where the wall used to be.

Axel Schultes: Maybe I learned something during a recent lecture I gave in Palermo (Italy). Afterwards, some German specialists in philosophy and German thinking—brilliant people, I must say—came up to me and said, ‘What you said about Berlin and what you are doing there with the Federal Chancellery (Bundeskanzleiamt), for us is what Ernst Bloch and Walter Benjamin talked about, especially when they looked at Italy and the cities in Italy. We noticed immediately in your work that (same) issue of porosity.’ Both used this term: Benjamin wrote a small article on Naples, and Bloch wrote about Italy as a whole.

We always had a tendency to avoid the term, ‘transparency.’ Transparency is usually the use of glass to make buildings less alienating to someone outside. But for us, glass is no material to create spaces; so transparency as we see it is depths of spaces or layering. Porosity is something much more precise—what we strive for. We wanted the same effect in Friedrichstrasse (Interior Mall): it should not be this close-up thing of the Galeries Lafayette (Jean Nouvel) or Ungers, where you only have some holes in it. Porosity for us is like a sponge—to enable a building to fill up with life, to turn a private space into a public one by penetrating it with a public space. The old buildings in Berlin are examples of this, with two, three, sometimes even four interior public spaces.

Berlin Baumschulenweg Crematory (1993)

COMPETITIONS: You are referring to the interior courtyards (Hinterhöfe)?

AS: Yes. Nothing of this sort exists anymore in Berlin. Most buildings (at the street) are flat, sometimes elegant, sometime ugly. The Galeries Lafayette, with all its glass, is as closed (to the outside) as one of Unger’s sandstone buildings. It’s the same issue in the construction of every building. Take, for instance, the Berlin Schloss (the palace in the center of Berlin), which was completely demolished after WWII, and which some people think should be resurrected. This has been on our mind constantly.*

It would be such a contrast to urbanism—needing to punch holes in it to get inside—open to all the people and all walks of life. I can give many examples of this, for me very northern, very restrained, very alien to everything which infuses a culture with life. All the people here like Kohlhof, Ungers, Kleihues, etc.; all have that tendency of closing. Even Libeskind—and maybe he doesn’t think about it or want to have it appear in such a manner—does it with the Jewish Museum where there is no penetration. There is always this hiding, this animosity to the urban fabric. They are not interested in breaking it up.

Bonn Art Museum – Competition (1985) Completion (1992)

Read more…

by Dan Madryga

Winning entry by Bjarke Ingels Group

Tirana, Albania might be the last place that many would associate with cutting edge architecture. The capital of a poor country still struggling to sweep away the lingering vestiges of the communist era, it is understandable that architecture and design have not always been a top priority. Yet in the face of the city’s struggles, Tirana is striving to reclaim and reshape its image and identity, and international design competitions are playing no small role in this movement. And while Tirana has yet to be associated with contemporary architecture, the implementation of these design competitions has introduced a handful of renowned architecture firms to the city with high hopes of bolstering the international image of Albania. In 2008, MVRDV won commission for a community master plan on Tirana Lake that will herald forward thinking, ecologically minded urban development. Earlier this year, Coop Himmelb(l)au won a competition for the new Albanian Parliament Building with a design intended to symbolize the transparency and openness of democracy. Most recently, Tirana can now add BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) of Denmark to these ranks as the winner of the New Mosque and Museum of Tirana & Religious Harmony Competition, an ambitious project aimed to further rekindle a tattered Albanian cultural identity.

The recent efforts to renew and improve the physical image of Tirana can be attributed in large part to the city’s three-term mayor, Edi Rama. With his background as an artist, Rama has launched a number of initiatives over his decade in office, intent on improving the aesthetic image of Tirana. The design competition for the mosque and cultural complex can be viewed as the latest component of his “Return to Identity” project, which has gone to great lengths to remove the many unsightly and illegally constructed buildings that plague the city and help provide a clean slate for more progressive architecture and urban design.

The Mosque and Museum competition focuses on reclaiming a key religious and cultural identity that was long suppressed by communism. While Albania claims three chief religions—a Muslim majority alongside significant Orthodox Christian and Catholic communities—a strict communist regime ruthlessly banned religion. For over four decades, Albanians were under the thumb of an atheist regime where religious practitioners could face humiliation, imprisonment, and even torture and execution. The anti-religious campaign reached its zenith in the 1960s, when most Mosques and churches were demolished, and a select few with architectural significance were converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, and youth centers.

The revival of religious institutions began with the 1990 collapse of the communist regime. Yet decades of suppression took their toll, with the vestiges of Albania’s religious heritage essentially reduced to rubble. While the two Christian religions have since regained centers of worship, after twenty-one years of restored religious freedom, Tirana still lacks a mosque suitable for serving the sizable Muslim population. Only one mosque still stands in the central city—the historic Et’hem Bey Mosque—certainly a potent symbol of Tirana’s Islamic heritage, but particularly inadequate in size to accommodate the large numbers who would want to worship there on special occasions.

Hence emphasis in the brief concerning the size of the building: a grand mosque that can adequately serve 1000 prayers on normal days, 5000 on Fridays, and up to 10,000 during holy feasts. Supporting this mosque, the program also specifies the design of a Center of Islamic Culture that will house teaching, learning, and research facilities including a library, multipurpose hall, and seminar classrooms.

Another component of the competition program, the Museum of Tirana and Religious Harmony, moves beyond the realm of the Muslim community in an explicit gesture to bring together citizens from all faiths and backgrounds. Aside from presenting the general history of Tirana, the museum will focus on the city’s religious heritage, highlighting both the turbulent moment of suppression under communism as well as the religious harmony that has since been reinstated. Educating the public about Islamic culture and promoting religious tolerance at a time when relations between religious communities are strained throughout the world is certainly a noble objective.

Underlining the importance of this project is its prominent site on Scanderbeg Square, the administrative and cultural center of Tirana where major government buildings share an expansive public space with museums and theaters. The square itself was the subject of a 2003 design competition that will eventually reclaim the urban center—at present a rather chaotic vehicular hub—as a pedestrian zone with a more human scale. Situated on triangular site adjacent to the Opera and Hotel Tirana, the Mosque and Cultural Center will be a highly visible component of Tirana’s urban landscape.

left: BIG site plan; right: rendering of Scanderbeg Square to appear after redesign (image by seARCH Architects)

The two-stage, international competition was organized by the City of Tirana and the Albanian Muslim community and advised by Nevat Sayin and Artan Hysa.

Over one hundred teams—the vast majority European—submitted qualifications for the first stage. In early March, the short-listing committee selected five teams to receive an honorarium of 45,000 Euros each to develop designs:

• Bjarke Ingels Group – Copenhagen, Denmark

• seARCH – Amsterdam, Holland

• Zaha Hadid Architects – London, UK

• Andreas Perea Ortega with NEXO – Madrid, Spain

• Architecture Studio – Paris, France

The designs were judged by a diverse European panel:

• Edi Rama – Mayor of Tirana, Albania

• Paul Boehm – architect, Cologne, Germany

• Vedran Mimica – Croatian architect; current director of the Berlage Institute

• Peter Swinnen – Partner and architect at 51N4E, Brussels

• Prof. Enzo Siviero – engineer; Professor at University IUAV, Venice

• Artan Shkreli – architect, Tirana, Albania

• Shyqyri Rreli – Muslim community representative

On 1 May 2011, the panel announced Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) as the winner.

Read more…

©Markus Bonauer/Michael Bölling, Berlin with capattistaubach Landschaftsarchitekten

©Markus Schietsch Architekten GmbH mit Lorenz Engster Landschaftsarchitektur & Städtebau GmbH

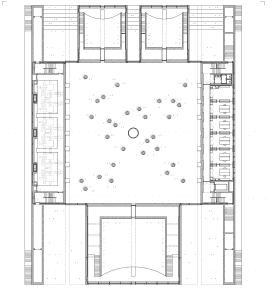

After two rounds of judging, beginning with 187 entries from around the world, the jury reduced the number of competitors to 28 in the first round, then finally settled on two first-place finalists in the second stage, one of which will be commissioned to design the Center. (One may assume that the limited number of entries in such an important competition was limited by the fact that the competition language was held in German.) The building itself is not the only project element, as a tunnel linking the Visitors Center in the Tiergarten to the Reichstag also is an essential part of the plan. The total cost of the project to the government is to be limited to 150€M.

Winners (2)

• Markus Bonauer/Michael Bölling, Berlin with capattistaubach Landschaftsarchitekten

• Markus Schietsch, Zürich with Lorenz Eugster Landschaftsarchitektur & Städtebau GmbH

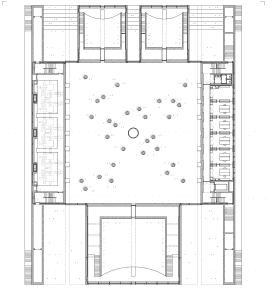

Site plan ©Markus Bonauer/Michael Bölling, Berlin with capattistaubach Landschaftsarchitekten

Site Plan ©Markus Schietsch Architekten GmbH mit Lorenz Engster Landschaftsarchitektur & Städtebau GmbH

Honorable Mentions (5)

• BGAA + FRPO Burgos & Garrido Arquitectos Asociados + FRPO Rodriguez & Oriol Arquitectos, Madrid (Spain) with VWA + UBERLAND, Vevey (Switzerland)

• bob-architektur BDA, Köln with FSWLA GmbH, Düsseldorf

• Henn GmbH, Berlin with Ingenieurgesellschaft BBP Bauconsulting mbH, Berlin

• Allmann Sattler Wappner Architekten GmbH, Munich with Schüller Landschaftsarchitekten, Munich

• ARGE KIM NALLEWEG Architekten und César Trujillo Moya, Berlin with TDB Landschaftsarchitektur Thomanek Duquesnoy Boemans Partnerschaft, Berlin

Read more…

Rosa Luxemburg Memorial by Mies van der Rohe

Background

Given the history of Rosa Luxemburg as a founder of the Spartacus Bund, a precursor to the German Communist Party, it would seem peculiar to many outside of Germany that a foundation bearing her name would be one of the largest in Germany. Rosa Luxemburg, although born in Poland, became famous during World War I in Berlin as an anti-war activist. She was murdered during the Communist uprising against the German government in 1919. In 1926, Mies van der Rohe was commissioned to design a monument commemorating her and Karl Liebknecht, co-founders of the Spartacus Bund (above). The monument was later demolished by the Nazis in 1935 and never rebuilt. One promising attempt to rebuild the memorial was abandoned when Mies withdrew his support for it—no doubt a product of the Cold War at the time—and Mies’s experiences with the McCarthy hearings at the Un- American Activities Committee.

Read more…

|

Helsinki Central Library, by ALA Architects (2012-2018)

The world has experienced a limited number of open competitions over the past three decades, but even with diminishing numbers, some stand out among projects in their categories that can’t be ignored for the high quality and degree of creativity they revealed. Included among those are several invited competitions that were extraordinary in their efforts to explore new avenues of institutional and museum design. Some might ask why the Vietnam Memorial is not mentioned here. Only included in our list are competitions that were covered by us, beginning in 1990 with COMPETITIONS magazine to the present day. As for what category a project under construction (Science Island), might belong to or fundraising still in progress (San Jose’s Urban Confluence or the Cold War Memorial competition, Wisconsin), we would classify the former as “built” and wait and see what happens with the latter—keeping our fingers crossed for a positive outcome.

Read More…

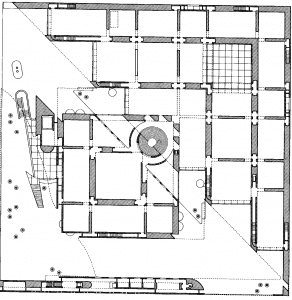

Young Architects in Competitions

When Competitions and a New Generation of Ideas Elevate Architectural Quality

by Jean-Pierre Chupin and G. Stanley Collyer

published by Potential Architecture Books, Montreal, Canada 2020

271 illustrations in color and black & white

Available in PDF and eBook formats

ISBN 9781988962047

What do the Vietnam Memorial, the St. Louis Arch, and the Sydney Opera House have in common? These world renowned landmarks were all designed by architects under the age of 40, and in each case they were selected through open competitions. At their best, design competitions can provide a singular opportunity for young and unknown architects to make their mark on the built environment and launch productive, fruitful careers. But what happens when design competitions are engineered to favor the established and experienced practitioners from the very outset?

This comprehensive new book written by Jean-Pierre Chupin (Canadian Competitions Catalogue) and Stanley Collyer (COMPETITIONS) highlights for the crucial role competitions have played in fostering the careers of young architects, and makes an argument against the trend of invited competitions and RFQs. The authors take an in-depth look at past competitions won by young architects and planners, and survey the state of competitions through the world on a region by region basis. The end result is a compelling argument for an inclusive approach to conducting international design competitions.

Download Young Architects in Competitions for free at the following link:

https://crc.umontreal.ca/en/publications-libre-acces/

RUR model perspective – ©RUR

New Kaohsiung Port and Cruise Terminal, Taiwan (2011-2020)

Reiser+Umemoto RUR Architecture PC/ Jesse Reiser – U.S.A.

with

Fei & Cheng Associates/Philip T.C. Fei –R.O.C. (Tendener)

This was probably the last international open competition result that was built in Taiwan. A later competition for the Keelung Harbor Service Building Competition, won by Neil Denari of the U.S., the result of a shortlisting procedure, was not built. The fact that the project by RUR was eventually completed—the result of the RUR/Fei & Cheng’s winning entry there—certainly goes back to the collaborative role of those to firms in winning the 2008 Taipei Pop Music Center competition, a collaboration that should not be underestimated in setting the stage for this competition.

Read more…

Winning entry ©Herzog de Meuron

In visiting any museum, one might wonder what important works of art are out of view in storage, possibly not considered high profile enough to see the light of day? In Korea, an answer to this question is in the making.

It can come as no surprise that museums are running out of storage space. This is not just the case with long established “western” museums, but elsewhere throughout the world as well. In Seoul, South Korea, such an issue has been addressed by planning for a new kind of storage facility, the Seouipul Open Storage Museum. The new institution will house artworks and artifacts of three major museums in Seoul: the Seoul Museum of Modern Art, the Seoul Museum of History, and the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

Read more…

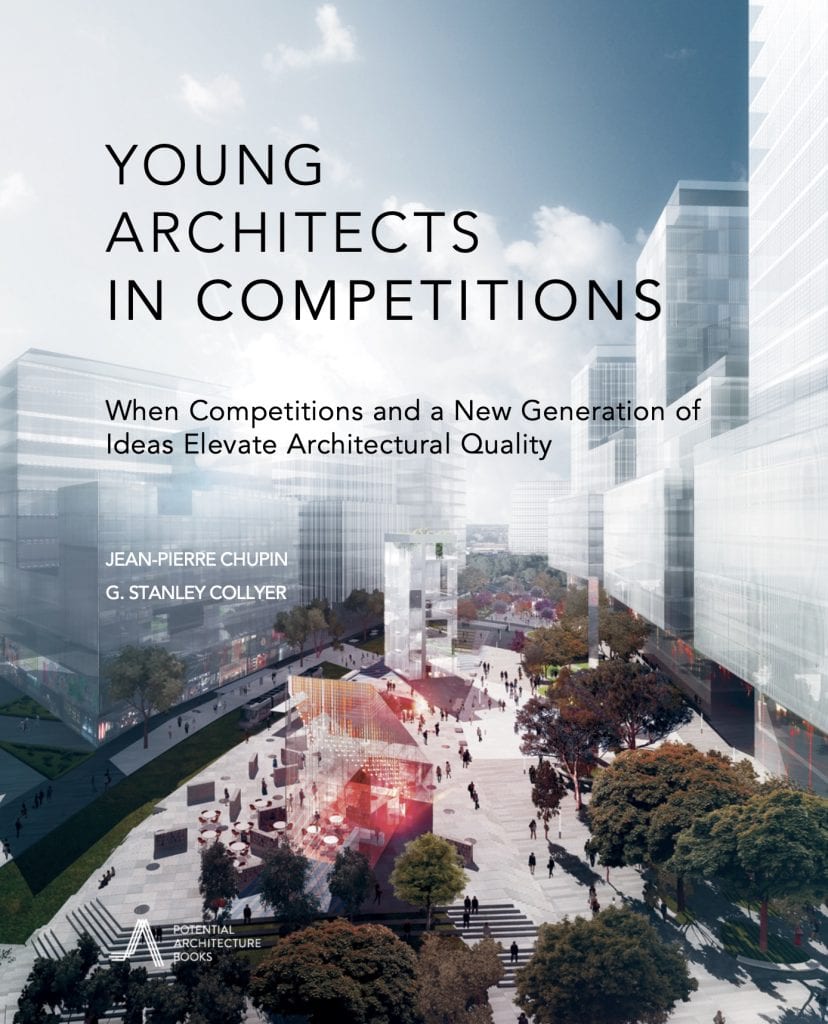

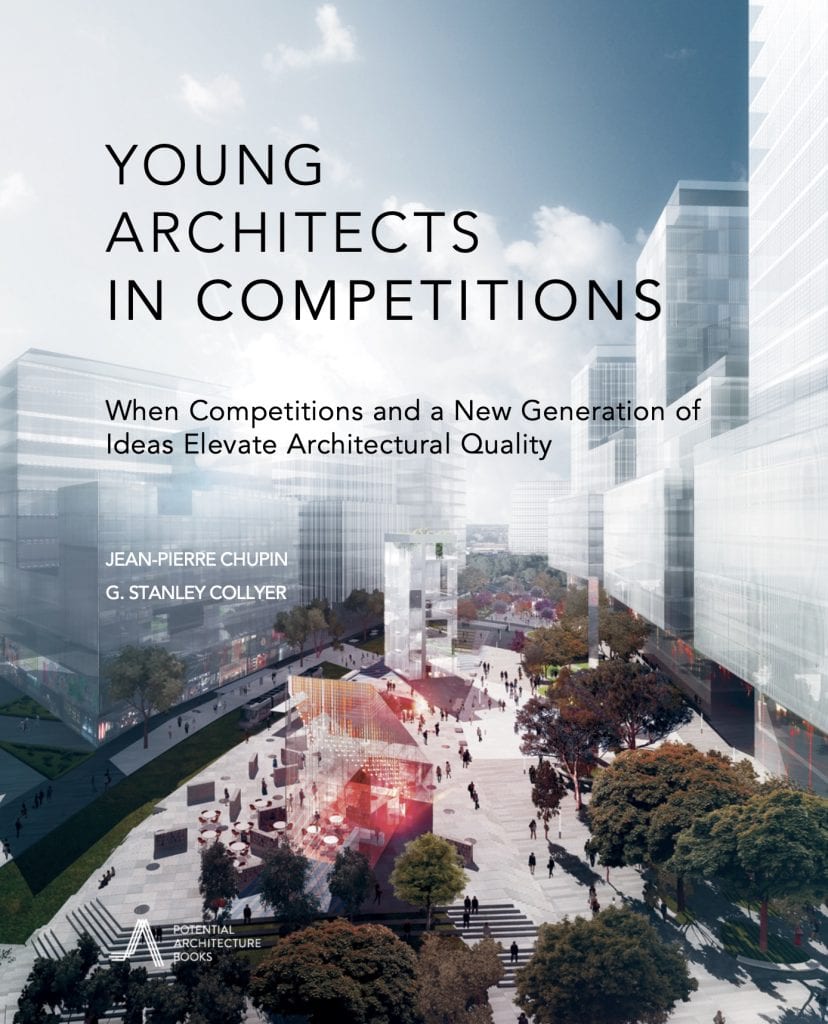

Belfast Looks Toward an Equitable and Sustainable Housing Model

Birdseye view of Mackie site ©Matthew Lloyd Architects

If one were to look for a theme that is common to most affordable housing models, public access has been based primarily on income, or to be more precise, the very lack of it. Here it is no different, with Belfast’s homeless problem posing a major concern. But the competition also hopes to address another of Belfast’s decades-long issues—its religious divide. There is an underlying assumption here that religion will play no part in a selection process. The competition’s local sponsor was “Take Back the City,” its membership consisting mainly of social advocates. In setting priorities for the housing model, the group interviewed potential future dwellers as well as stakeholders to determine the nature of this model. Among those actions taken was the “photo- mapping of available land in Belfast, which could be used to tackle the housing crisis. Since 2020, (the group) hosted seminars that brought together international experts and homeless people with the goal of finding solutions. Surveys and workshops involving local people, housing associations and council duty-bearers have explored the potential of the Mackie’s site.” This research was the basis for the competition launched in 2022.

Read more…

Alster Swimming Pool after restoration (2023)

Linking Two Competitions with Three Modernist Projects

Hardly a week goes by without the news of another architectural icon being threatened with demolition. A modernist swimming pool in Hamburg, Germany belonged in this category, even though the concrete shell roof had been placed under landmark status. When the possibility of being replaced by a high-rise building, it came to the notice of architects at von Gerkan Marg Partners (gmp), who in collaboration with schlaich bergermann partner (sbp), developed a feasibility study that became the basis for the decision to retain and refurbish the building.

Read more…

|