with Stanley Collyer

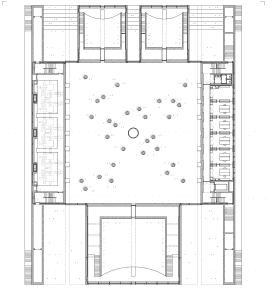

Bundeskanzleramt Berlin Competition (1996); Completion (2000) Photo: courtesy Schultes Frank Architekten

COMPETITIONS: In our last conversation, we talked about the whole issue of Berlin’s identity and what approach one should use in reconstructing the urban fabric between East and West—where the wall used to be.

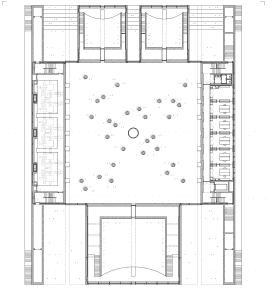

Axel Schultes: Maybe I learned something during a recent lecture I gave in Palermo (Italy). Afterwards, some German specialists in philosophy and German thinking—brilliant people, I must say—came up to me and said, ‘What you said about Berlin and what you are doing there with the Federal Chancellery (Bundeskanzleiamt), for us is what Ernst Bloch and Walter Benjamin talked about, especially when they looked at Italy and the cities in Italy. We noticed immediately in your work that (same) issue of porosity.’ Both used this term: Benjamin wrote a small article on Naples, and Bloch wrote about Italy as a whole.

We always had a tendency to avoid the term, ‘transparency.’ Transparency is usually the use of glass to make buildings less alienating to someone outside. But for us, glass is no material to create spaces; so transparency as we see it is depths of spaces or layering. Porosity is something much more precise—what we strive for. We wanted the same effect in Friedrichstrasse (Interior Mall): it should not be this close-up thing of the Galeries Lafayette (Jean Nouvel) or Ungers, where you only have some holes in it. Porosity for us is like a sponge—to enable a building to fill up with life, to turn a private space into a public one by penetrating it with a public space. The old buildings in Berlin are examples of this, with two, three, sometimes even four interior public spaces.

Berlin Baumschulenweg Crematory (1993)

COMPETITIONS: You are referring to the interior courtyards (Hinterhöfe)?

AS: Yes. Nothing of this sort exists anymore in Berlin. Most buildings (at the street) are flat, sometimes elegant, sometime ugly. The Galeries Lafayette, with all its glass, is as closed (to the outside) as one of Unger’s sandstone buildings. It’s the same issue in the construction of every building. Take, for instance, the Berlin Schloss (the palace in the center of Berlin), which was completely demolished after WWII, and which some people think should be resurrected. This has been on our mind constantly.*

It would be such a contrast to urbanism—needing to punch holes in it to get inside—open to all the people and all walks of life. I can give many examples of this, for me very northern, very restrained, very alien to everything which infuses a culture with life. All the people here like Kohlhof, Ungers, Kleihues, etc.; all have that tendency of closing. Even Libeskind—and maybe he doesn’t think about it or want to have it appear in such a manner—does it with the Jewish Museum where there is no penetration. There is always this hiding, this animosity to the urban fabric. They are not interested in breaking it up.

Bonn Art Museum – Competition (1985) Completion (1992)

Read more…

by Miguel Ruano

Aerial view of Prado (left); site outline (right)

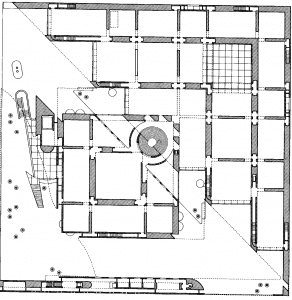

In October 1993, rainwater was seen filtering down through the cracked, poorly maintained roof of the Prado museum’s 18th century building, directly threatening some of the world’s greatest masterpieces, including Velazquez’s “Las Meninas.” Alarm bells went off, both in the building and in the media, and the public learned what until then only a few insiders knew: that one of the best and most famous museums in the world had been in desperate need of repair and expansion for decades. As an emergency solution, seven architects were requested in 1994 by the Ministry of Culture to submit their own ideas for the refurbishment of the museum’s roof. At the same time, the notion of a more ambitious, high-profile international competition to design an extension to the Prado began to take shape.

The competition was to be organized by the Ministry of Culture of Spain, with the technical assistance of the UIA (International Union of Architects) and UNESCO’s endorsement. With government elections coming up, the politicians in charge of the problem needed to demonstrate that the Prado was a high priority.. Thus, the media was immediately informed to ensure complete and regular coverage. From the start, the competition took on the character of a political public relations affair, which in the end, would come back to haunt them.

The Rules

The Prado Competition began in earnest in February 1995, when the Museum’s board of trustees approved the competition rules, which were in turn accepted by the Ministry of Culture of the ruling Socialist Party. In theory, there had been a top-level agreement on the approach to be taken to address the museum’s problems between the Socialist government and the main opposition party, the Conservatives, who by then were already expected to prevail in the next election. The reason for such agreement was obvious—to make sure that the process would not be overturned for political reasons.

Subsequently, it would appear that this agreement had been on a shaky foundation from the very beginning. According to the rules, which were fraught with ambiguities and inconsistencies, the Prado was going to double its size to 40,000 m2 by the year 2000 via its expansion into three adjacent buildings. This brought about the first conflicts, as some of the owners of the buildings in question denied any association with the expansion plans. This included Spain’s Catholic church, which took the Ministry to court. Madrid’s City hall, already under Conservative Party control before the elections, hardly appreciated such a high-profile initiative taken by the lame-duck Socialist government—directed at the very heart of the city. Moreover, at the insistence of the Museum’s Board of Trustees, a clause declaring that the “current architectural image of the main building could not be disturbed” had to be included in the rules (and it was). The original competition schedule had to be delayed two months, and last-minute, but significant, amendments had to be made to the rules, giving everyone a feeling of improvisation. The whole venture started on a note of controversy.

The Entrants

According to the organizer’s estimates, 500 architects from all over the world were expected to register for the competition. Some were individually invited to enter, including Isozaki, Ando, Hollein, Wilford, Salmona, Macary, Pelli and Siza (who immediately declared he would not take part, and then was asked to become a member of the jury, to which he said no as well). Others, like Foster and Calatrava, both well-known to the Spanish general public, had already confirmed their interest, which raised everybody’s expectations after their much publicized showdown at the Reichstag competition in Berlin.

Finalist – Distinction (2)

Alberto Martinez/Beatriz Matos

Madrid, Spain

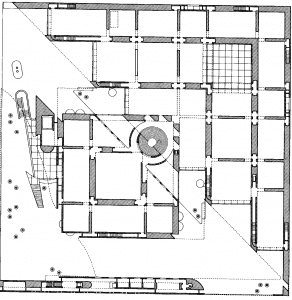

Second Place in First Round (11 votes)

This low-impact proposal creates a new urban space in front of the Prado’s historic building back elevation, which now acquires a new character as an urban facade. Below this platform, a new three-story underground structure houses the entrance hall, auditorium, cafeteria, library and storage areas. A transversal gap across the plaza brings natural light into the underground structure. From this, the building connects with a new adjacent structure, located on the old covent’s grounds, which houses the museum’s services (restoration workshops, offices, etc.) -MR

Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

As architects learned more about the competition’s details, skepticism and even open criticism heightened—from architectural circles as well as in the media. Some internationally famous names such as Ungers or Ando decided not to register, arguing either work overload or disagreement with the competition’s rules. The organizers, however, seemed to be satisfied with the fact that well-known architects like Foster, Moneo, Calatrava, Tusquets, Bohigas, Navarro, Eisenman or Benevolo had decided to enter, thus giving credibility to the initiative.

Interestingly enough, while the organization was obviously very forthcoming in disclosing names of high-profile participants, they would not supply a complete list of entrants, arguing that the competition was anonymous and, as a consequence, only overall registration statistics could be released.

Finalist – Distinction (2)

Jean-Paul Duerig and Philippe Rami

Zürich, Switzerland

Seventh place in stage 1 semi-final round (6 votes) – tied with E. Zoido

This blunt proposal attaches a new gray granite and red brick structure, 300m (1,000 feet) long, to the Prado’s rear facade to house the entrance hall, exhibition halls, auditorium, cafeteria and shops. The nearby convent becomes a four-story building for the library, the restoration workshops, and the museum’s services and offices, while the old building will be used exclusively for exhibitions. The whole museum complex (four existent buildings, plus the proposed structure) are linked by underground connectors. –MR

above

Aerial view of model

left and below

Images from competition boards ©Ministry of Education and Culture

Read more…

Sponsors/organizers: Peabody, Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA)

Location: London Borough of Bexley.

The shortlisted teams (in alphabetical order) are:

Adam Khan Architects, UK Architecture 00 Ltd / Studio Weave, UK Bisset Adams Ltd, UK Keith Williams Architects, UK Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter, Norway

The new library and civic building will lie

Read more…

Sponsors: Barbican, the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama

Process: RfQ, shortlist

The need for a new state-of-the-art venue was the result of a study, drawn up by Arup and Arup Associates among others, which said London lacked a venue with ‘brilliance, immediacy, depth, richness and warmth’ and

Read more…

Sponsor: Università Iuav di Venezia, Italy Type: International, anonymous, one-stage Eligibility: Limited to architects and engineers under the age of 40 Fee: None! Languages: Italian, English Awards: First prize €10.000 Second prize €4.500 Third prize €2.000

Timetable:

20 October 2017 – Registration deadline 3 November 2017 – Submission deadline

Challenge:

The aim of the contest

Read more…

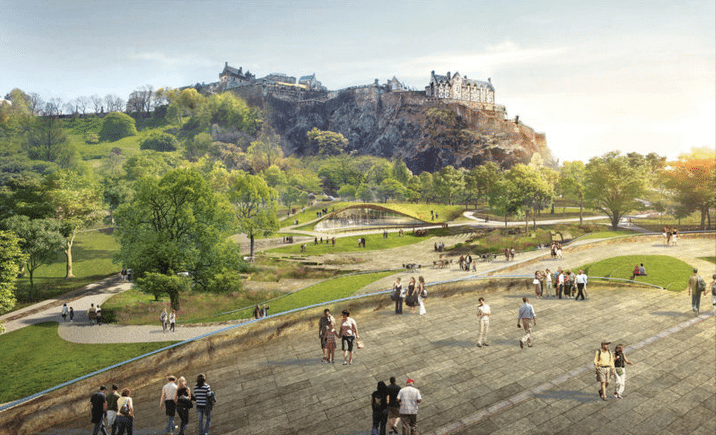

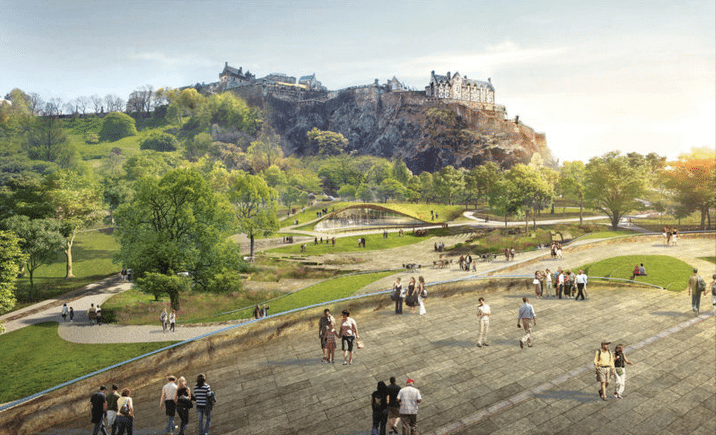

Winning entry by wHY (Image © wHY Architecture)

By winning the Ross Pavilion International competition, Los Angeles-based wHY Architecture’s efforts as a competitor in several recent high-profile invited competitions has finally borne fruit. Among the seven shortlisted finalists from the 125 teams that submitted EOIs from around the world, wHY’s design separated itself from the others by featuring their pavilion as an integral part of the landscape, rather than a pavilion as activities structure representing a central focal point of the site.

Winning entry by wHY (Image © wHY Architecture)

Even while concentrating on the landscape, wHY’s sustainability concept revealed an interesting tactic, using one of its favorite curvilinear ideas as a principal design element. To anyone who remembered the wHY design for the Mumbai City Museum extension, this was combining architecture with landscape in their representation of a “butterfly” motif. By doing so, a garden is transformed into something almost magical, while lower key on an intellectual level. According to the jury, “The team’s concept design as ‘a beautiful and intensely appealing proposal that complemented, but did not compete with, the skyline of the City and the Castle.’ They liked the concept of the activated community space with a democratic spirit, potentially creating a new and welcoming focus for the City’s festivals while appreciating that the team’s design balanced this with a strong approach to the smaller, intimate spaces within the wider Gardens.” Finally, the performance function did not simply turn into a high-profile icon, but became a logical extension of the landscape.

Winning entry by wHY (Images © wHY Architecture)

The shortlisted finalists were:

• wHY, GRAS, Groves-Raines Architects, Arup, Studio Yann Kersalé, O Street, Stuco, Creative Concern, Noel Kingsbury, Atelier Ten and Lawrence Barth (Winner)

• Adjaye Associates with Morgan McDonnell, BuroHappold Engineering, Plan A Consultants, JLL, Turley, Arup, Sandy Brown, Charcoalblue, AOC Archaeology, Studio LR, FMDC, Interserve and Thomas & Adamson

• Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) with JM Architects, WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff, GROSS.MAX., Charcoalblue, Speirs + Major, JLL, Alan Baxter and People Friendly

• Flanagan Lawrence with Gillespies, Expedition Engineering, JLL, Arup and Alan Baxter

• Page \ Park Architects, West 8 Landscape Architects and BuroHappold Engineering with Charcoalblue and Muir Smith Evans

• Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter with GROSS.MAX., AECOM, Charcoalblue, Groves-Raines Architects and Forbes Massie Studio

• William Matthews Associates and Sou Fujimoto Architects with BuroHappold Engineering, GROSS.MAX., Purcell, Scott Hobbs Planning and Filippo Bolognese

Read more…

|

Helsinki Central Library, by ALA Architects (2012-2018)

The world has experienced a limited number of open competitions over the past three decades, but even with diminishing numbers, some stand out among projects in their categories that can’t be ignored for the high quality and degree of creativity they revealed. Included among those are several invited competitions that were extraordinary in their efforts to explore new avenues of institutional and museum design. Some might ask why the Vietnam Memorial is not mentioned here. Only included in our list are competitions that were covered by us, beginning in 1990 with COMPETITIONS magazine to the present day. As for what category a project under construction (Science Island), might belong to or fundraising still in progress (San Jose’s Urban Confluence or the Cold War Memorial competition, Wisconsin), we would classify the former as “built” and wait and see what happens with the latter—keeping our fingers crossed for a positive outcome.

Read More…

Young Architects in Competitions

When Competitions and a New Generation of Ideas Elevate Architectural Quality

by Jean-Pierre Chupin and G. Stanley Collyer

published by Potential Architecture Books, Montreal, Canada 2020

271 illustrations in color and black & white

Available in PDF and eBook formats

ISBN 9781988962047

What do the Vietnam Memorial, the St. Louis Arch, and the Sydney Opera House have in common? These world renowned landmarks were all designed by architects under the age of 40, and in each case they were selected through open competitions. At their best, design competitions can provide a singular opportunity for young and unknown architects to make their mark on the built environment and launch productive, fruitful careers. But what happens when design competitions are engineered to favor the established and experienced practitioners from the very outset?

This comprehensive new book written by Jean-Pierre Chupin (Canadian Competitions Catalogue) and Stanley Collyer (COMPETITIONS) highlights for the crucial role competitions have played in fostering the careers of young architects, and makes an argument against the trend of invited competitions and RFQs. The authors take an in-depth look at past competitions won by young architects and planners, and survey the state of competitions through the world on a region by region basis. The end result is a compelling argument for an inclusive approach to conducting international design competitions.

Download Young Architects in Competitions for free at the following link:

https://crc.umontreal.ca/en/publications-libre-acces/

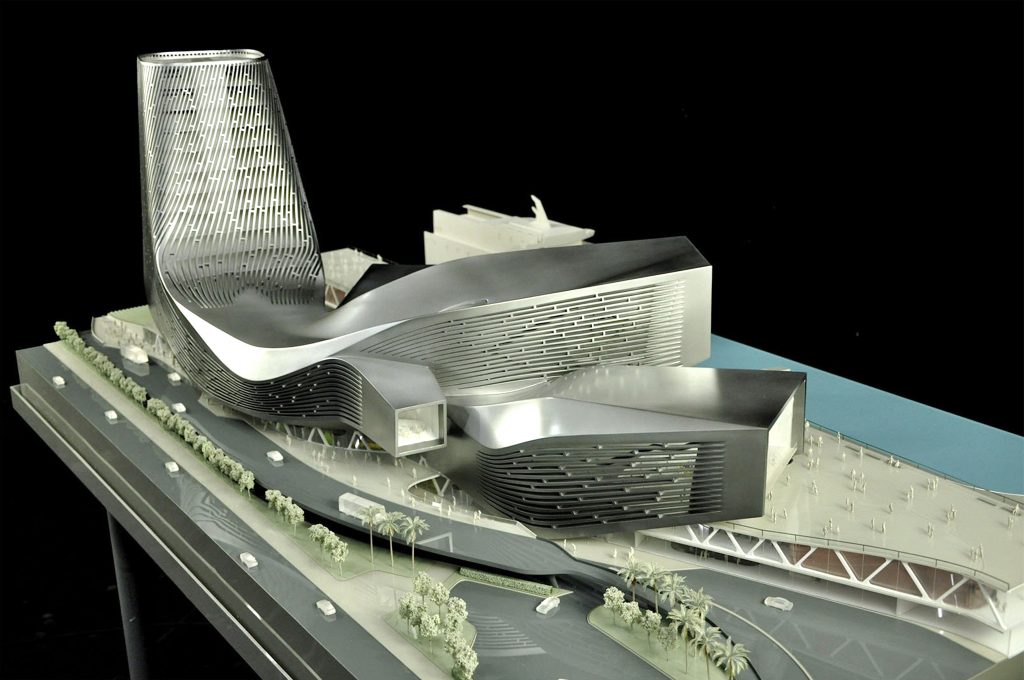

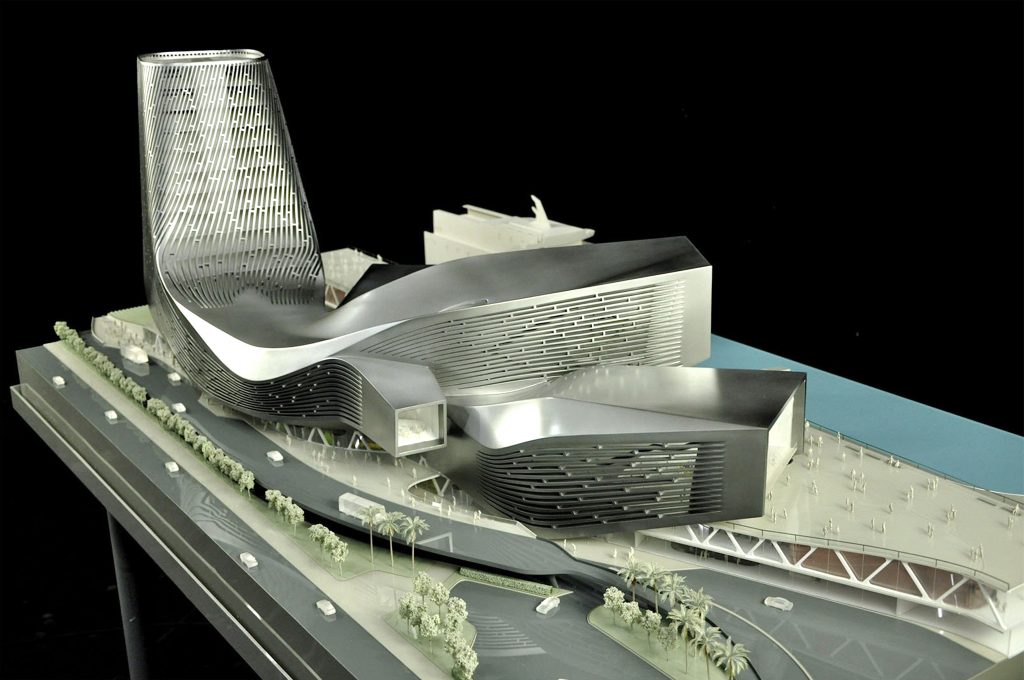

RUR model perspective – ©RUR

New Kaohsiung Port and Cruise Terminal, Taiwan (2011-2020)

Reiser+Umemoto RUR Architecture PC/ Jesse Reiser – U.S.A.

with

Fei & Cheng Associates/Philip T.C. Fei –R.O.C. (Tendener)

This was probably the last international open competition result that was built in Taiwan. A later competition for the Keelung Harbor Service Building Competition, won by Neil Denari of the U.S., the result of a shortlisting procedure, was not built. The fact that the project by RUR was eventually completed—the result of the RUR/Fei & Cheng’s winning entry there—certainly goes back to the collaborative role of those to firms in winning the 2008 Taipei Pop Music Center competition, a collaboration that should not be underestimated in setting the stage for this competition.

Read more…

Winning entry ©Herzog de Meuron

In visiting any museum, one might wonder what important works of art are out of view in storage, possibly not considered high profile enough to see the light of day? In Korea, an answer to this question is in the making.

It can come as no surprise that museums are running out of storage space. This is not just the case with long established “western” museums, but elsewhere throughout the world as well. In Seoul, South Korea, such an issue has been addressed by planning for a new kind of storage facility, the Seouipul Open Storage Museum. The new institution will house artworks and artifacts of three major museums in Seoul: the Seoul Museum of Modern Art, the Seoul Museum of History, and the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

Read more…

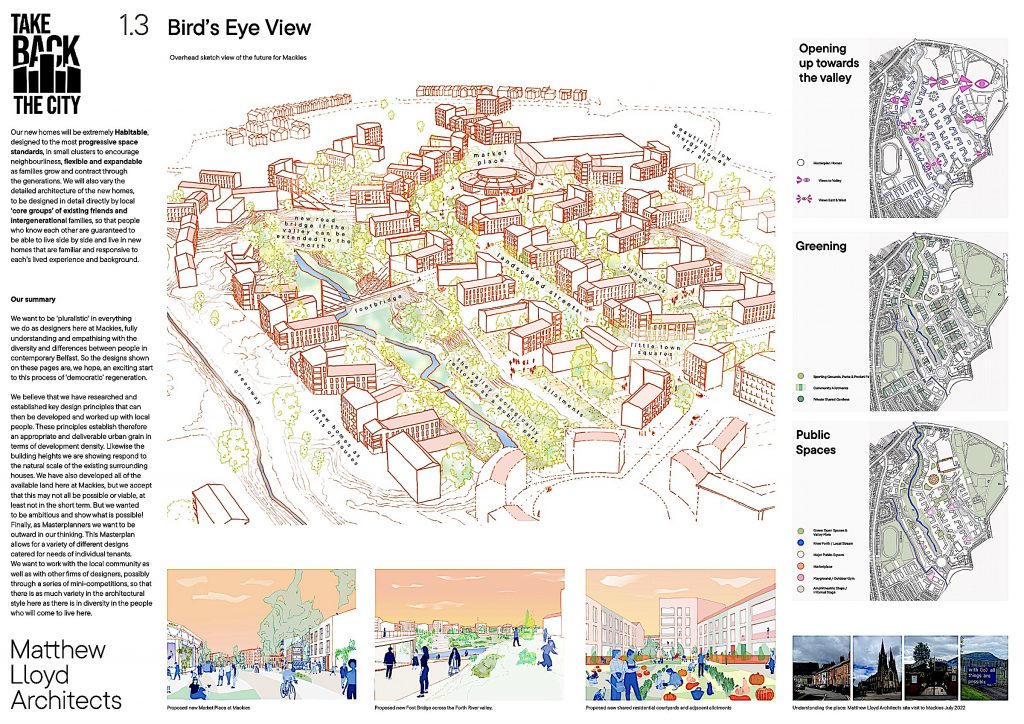

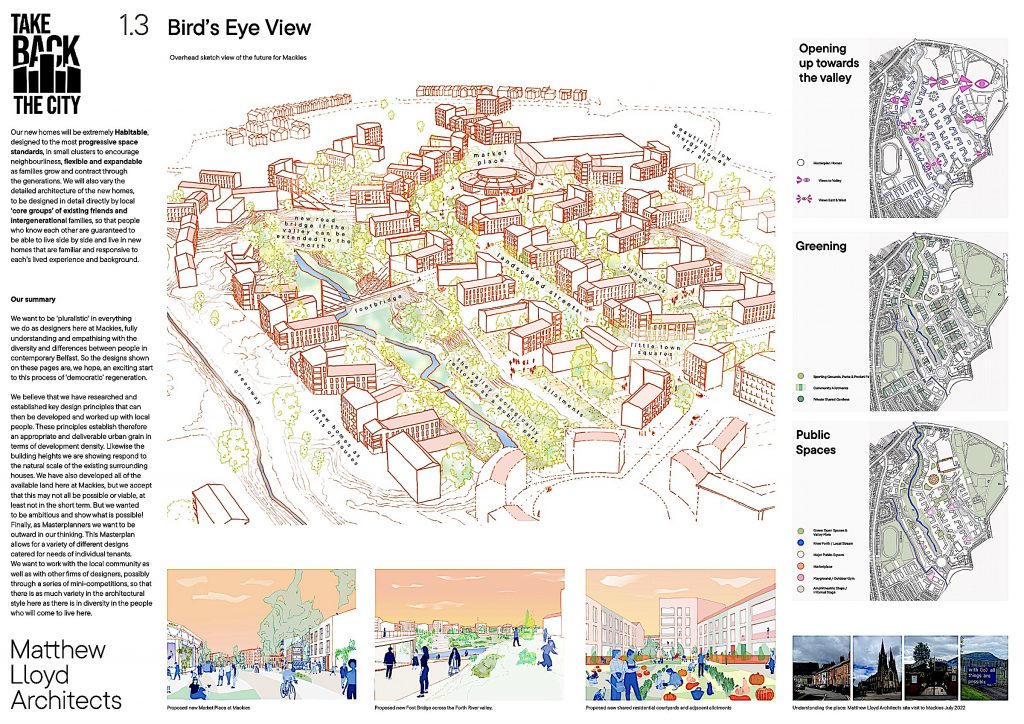

Belfast Looks Toward an Equitable and Sustainable Housing Model

Birdseye view of Mackie site ©Matthew Lloyd Architects

If one were to look for a theme that is common to most affordable housing models, public access has been based primarily on income, or to be more precise, the very lack of it. Here it is no different, with Belfast’s homeless problem posing a major concern. But the competition also hopes to address another of Belfast’s decades-long issues—its religious divide. There is an underlying assumption here that religion will play no part in a selection process. The competition’s local sponsor was “Take Back the City,” its membership consisting mainly of social advocates. In setting priorities for the housing model, the group interviewed potential future dwellers as well as stakeholders to determine the nature of this model. Among those actions taken was the “photo- mapping of available land in Belfast, which could be used to tackle the housing crisis. Since 2020, (the group) hosted seminars that brought together international experts and homeless people with the goal of finding solutions. Surveys and workshops involving local people, housing associations and council duty-bearers have explored the potential of the Mackie’s site.” This research was the basis for the competition launched in 2022.

Read more…

Alster Swimming Pool after restoration (2023)

Linking Two Competitions with Three Modernist Projects

Hardly a week goes by without the news of another architectural icon being threatened with demolition. A modernist swimming pool in Hamburg, Germany belonged in this category, even though the concrete shell roof had been placed under landmark status. When the possibility of being replaced by a high-rise building, it came to the notice of architects at von Gerkan Marg Partners (gmp), who in collaboration with schlaich bergermann partner (sbp), developed a feasibility study that became the basis for the decision to retain and refurbish the building.

Read more…

|