1st Place entry by M.A.M.O.T.H

For years, the earth has long been the basic construction material for houses in rural Ghana. Although 98% of the houses in the Abetenim area of Ashanti province—typical of warm, humid climate conditions—are made of earth, stereotypes about this building type persist because of eroding which takes place from poor construction and water damage. This has resulted in a stigma associated with mud architecture and the local perception that mud architecture is only for the poor. Instead of earth, metal and cement block have become the material of choice—at a considerable expense. In light of this problem, the Nka Foundation, a non-profit organization dealing with art and design in Africa, staged the Mud House Design Competition—to encourage designers, architects and builders to use their creativity to come up with innovative designs for modest, affordable homes that can be built locally. The focus of the design was to aim at creating a single family and semi-urban house type that would be a place to live, a place to rest, store modest belongings, and feel safe. What was the preferred construction method for the winning entries? It could be cob construction, rammed earth, mud brick, cast earth (poured earth) by formwork, or any other earth construction techniques that can be easily learned by local labor. Roofing design could be of vault, fired mud roof, or corrugated zinc sheets, which is the conventional roofing materials, because zinc roofing withstands the heavy rainfall better. As a prototype, the intended solution should be a durable mud house that promotes open source design for the continuity of building with earth for a more sustainable future. The house was to include a kitchen, living area, bedrooms and a toilet. The maximum cost of the house was to be $6,000, for which each entry was required to present a detailed budget. The Process

After a Preselection Jury of experts examined all of the entries, it was charged with shortlisting 20 for adjudication by a Grand Jury. The members of the latter were:

ÂÂÂÂÂÂ

• Belinda van Buiten, Utrecht, The Netherlands

• Marcio Albuquerque Buson, University of Brasilia

• Mariana Correia, Escola Superior Gallaecia, Portugal

• Toby Cumberbatch, The Cooper Union, New York

• Ahmad Hamid, Ahmad Hamid Architects, Egypt

• Rowland Keable, UNESCO Chair on Earthen Architecture

• Bruno Marques, Oporto Lusiada University, Portugal

• John Quale, Professor, University of New Mexico, USA

• Roland Rael, University of California, Berkeley

• Humberto Varum, University of Porto, Portugal

According to John Quale, he agreed to participate as a juror because he found the topic to be quite interesting. The selection process by the Grand Jury did not, however, take place face-to-face, but electronically. A web interface during the final stages of the process did occur, resulting in the final ranking of the entries. Prof. Quale found this to be an adequate method to adjudicate the designs, as this was obviously a competition with a limited budget, obviating the cost of impaneling the jury on-site. Judging criteria involved the functionality, aesthetics and technical factors to the degree to the degree that the design responded to the design program. The Winning Designs Of the short-listed projects (20), there were three winners. Jurors awarded prizes for first, second and third place consisting of a commemorative plague and cash prizes to the winning designs as follows: 1st prize—$1,500 or construction of the design in Ghana, plus a short trip to Ghana for the opening ceremony once construction is completed (in case the winner is not located in Ghana and to a maximum of 1 person); 2nd prize—Construction or $1,000 and 3rd prize—construction or $500.

Read more…

Interview with Stanley Collyer

FIU School of Architecture, Miami, FL, 1999-2003 (© Peter Mauss)

Read more…

by Dan Madryga

The finalists (from left to right): Perkins+Will, Adrian Smith+Gordon Gill, Goettsch Partners

Northwestern University is getting a major architectural facelift. Over the past few years, the university has staged several invited design competitions for large-scale building projects on its Chicago and Evanston campuses. A new 152,000 square foot building for the Bienen School of Music and Communication, designed by Goettsch Partners, is currently under construction and slated to open later this year. Meanwhile the 410,000 square foot Kellogg School of Business—for which Toronto firm KPMB beat out Kohn Pedersen Fox, Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill, and Pelli, Clark & Pelli for the commission—is expected to be ready for occupancy in 2016. As large as these projects are, Northwestern’s most recent invited competition dwarves them both in scale, budget, and ambition: a brand new Medical Research Center for the Feinberg School of Medicine.

Bienen School of Music © Goettsch Partners

ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

Kellogg School of Business © KPMB

The new Medical Research Center is a huge undertaking for Northwestern. Once complete it will introduce 1.2 million square feet of state-of-the-art lab space, with which the University expects to attract an additional $150 million a year for medical research, as well as create 2,000 new full-time jobs. Needless to say, the project is at the forefront of the university’s projected master plan.

Of course the architectural evolution of any urban campus necessitates some selective purging of the existing building stock. For the Medical Research Center’s central location on the Chicago campus, this has unfortunately meant the loss of Bertrand Goldberg’s 1975 Prentice Women’s Hospital. This move created no small amount of controversy amongst preservationists and fans of Goldberg’s distinctive, sculptural concrete cloverleaf form. Goldberg was a Chicago architect—a protégé of Mies van der Rohe—who also designed the instantly recognizable twin corncob towers of Marina City. Originally hailed for its innovative engineering and striking form, the Prentice took an innovative approach to organizing medical wards in clusters, thus lending to its distinct form. General reactions have always been mixed: for some it was an iconic work of Brutalism, for others it was simply an eyesore. Either way the hospital was clearly dated by the 21st century standards of functionality, and Northwestern’s development future did not include the Prentice.

Proponents of the Prentice pulled out all the stops to try and save the endangered hospital. Preservationist groups sought to protect it with a Landmark status designation that was ultimately denied. Chicago’s Studio Gang offered up a striking design idea that would save and incorporate the Prentice into the new research center. The efforts even extended to an ideas competition. In 2012, the Chicago Architectural Club organized “Future Prentice” as the timely theme of the annual Chicago Prize Competition. Entrants were challenged to find creative solutions for repurposing the old hospital building, in hopes that thought-provoking design could spark a useful public dialogue about solutions that went beyond full-on preservation or wholesale demolition. In addition to the 71 entries received, the Chicago Architectural Club commissioned designs from ten up-and-coming local architecture firms. Together these 81 ideas were displayed at the Chicago Architecture Foundation’s “Reconsidering an Icon” exhibit in late 2012 and early 2013.

The Future Prentice entries ranged from compelling yet largely grounded adaptive reuse ideas (the first prize entry by Cyril Marsollier and Wallo Villacorta imagines the Prentice’s distinctive concrete shell as a museum presented amongst the boxy volumes of a new research lab facility), to wildly left-field theoretical concepts (the second prize entry by Noel Turgeon and Natalya Egon, where various architectural additions are vertically stacked upon the Prentice to form a “timeline of trends in architecture”). In the end, the competition might have created an interesting dialogue but not with the people who really needed convincing. Given the longstanding plans to demolish the vacant hospital, Northwestern made it clear that all ideas for saving the Prentice would not be seriously reviewed by the University. Like the attempts to enact landmark status, the Future Prentice ideas competition was too little, too late.

Not long after the ideas competition came and went, Northwestern officially released their request for qualifications for the new Medical Research Center, with proposals due in April 2013. The RFQ was sent to 23 architecture firms, six of which were local Chicago firms, and most of which had previous experience in large research and medical projects.

Northwestern’s program called for a research center that would be implemented in two phases. Phase 1 will consist of a 600,000 square foot, 12-story mid-rise complex to fit the former site of the Prentice, with a groundbreaking slated for early 2015 and completion forecasted for 2018 or 2019. It will also serve as a base for the second phase, capping Phase 1 with a multistory tower featuring even more lab space and offices. It should be noted that there is currently no timetable or funding in place for the Phase 2 tower. Thus it is of particular importance that the design for Phase 1 does not end up looking like a vacant pedestal, should Northwestern’s long-term development goals not pan out.

The design criteria included: an iconic design that respected the campus context and would be a major asset to Northwestern, the Streeterville neighborhood, and the Greater Chicago community; a building that best met all the functional needs of the Medical School; a building that could be easily implemented in two phases; a design that respected and enhanced the neighborhood connections at ground level (particularly with the labs of the adjacent Lurie Medical Research Center); and a design that provided extensive green space. The University also expected at minimum a LEED silver ranking.

Similar to Northwestern’s most recent invited competitions, the RFQ procedure was a hybrid between a pure design competition and an interview. Or rather a series of interviews, as the shortlisted teams underwent a series of meetings during the design phase with the client group. The university prefers that the names of this evaluation committee remain anonymous, although Northwestern spokesperson Alan Cubbage has disclosed that the group included members of the University Board of Trustees as well as key administrators of the Feinberg School of Medicine. Two outside architects also sat in as advisors.

During these design meetings, the committee offered comments and critiques to each shortlisted team. Northwestern has chosen to keep the specifics of these meetings confidential, but we do know through reliable sources that the each team felt that the evaluation comments were well founded, and that no single competitor was singled out for criticism.

By November of 2013, the three shortlisted teams final designs were ready for a final verdict. In a gesture of transparency, Northwestern officially unveiled the resulting shortlist designs in an exhibit at the Lurie Medical Research Center. The university welcomed and recorded comments from faculty, staff, students, and other visitors to this public display. The three projects on display were by Perkins+ Will, Adrian Smith+Gordon Gill, and Goettsch Partners. It is good to see that all three firms have local Chicago offices; it seems fitting to replace a building by the indelibly Chicagoan architect Goldberg with a new generation of successors.

A casual observer of the shortlisted designs could be forgiven for finding them all remarkably similar. In fact, no one design stands out as wildly out of the box, an obvious winner. Instead we see three elegant, highly competent, if rather predictable options. Part of this stems from the nature of the building program—the rigid constraints of medical and research facilities often have a way of confining creativity. There’s also the persistent issue of making glazed skyscrapers energy efficient. Each entry uses high-performance building skins, which give them similar façade materiality and depth, not to mention employment of textbook sun shading techniques (cue the obligatory vertical fritted glass fins on the east and west facades). Just as the chunky Brutalism of the Prentice had become emblematic of 1970s modern architecture, the sleek, crystalline forms of the shortlist are very much of our own time. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it would have been interesting to see at least one unconventional curve ball, even if it had no chance of winning the commission. *

Read more…

|

Helsinki Central Library, by ALA Architects (2012-2018)

The world has experienced a limited number of open competitions over the past three decades, but even with diminishing numbers, some stand out among projects in their categories that can’t be ignored for the high quality and degree of creativity they revealed. Included among those are several invited competitions that were extraordinary in their efforts to explore new avenues of institutional and museum design. Some might ask why the Vietnam Memorial is not mentioned here. Only included in our list are competitions that were covered by us, beginning in 1990 with COMPETITIONS magazine to the present day. As for what category a project under construction (Science Island), might belong to or fundraising still in progress (San Jose’s Urban Confluence or the Cold War Memorial competition, Wisconsin), we would classify the former as “built” and wait and see what happens with the latter—keeping our fingers crossed for a positive outcome.

Read More…

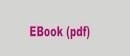

Young Architects in Competitions

When Competitions and a New Generation of Ideas Elevate Architectural Quality

by Jean-Pierre Chupin and G. Stanley Collyer

published by Potential Architecture Books, Montreal, Canada 2020

271 illustrations in color and black & white

Available in PDF and eBook formats

ISBN 9781988962047

What do the Vietnam Memorial, the St. Louis Arch, and the Sydney Opera House have in common? These world renowned landmarks were all designed by architects under the age of 40, and in each case they were selected through open competitions. At their best, design competitions can provide a singular opportunity for young and unknown architects to make their mark on the built environment and launch productive, fruitful careers. But what happens when design competitions are engineered to favor the established and experienced practitioners from the very outset?

This comprehensive new book written by Jean-Pierre Chupin (Canadian Competitions Catalogue) and Stanley Collyer (COMPETITIONS) highlights for the crucial role competitions have played in fostering the careers of young architects, and makes an argument against the trend of invited competitions and RFQs. The authors take an in-depth look at past competitions won by young architects and planners, and survey the state of competitions through the world on a region by region basis. The end result is a compelling argument for an inclusive approach to conducting international design competitions.

Download Young Architects in Competitions for free at the following link:

https://crc.umontreal.ca/en/publications-libre-acces/

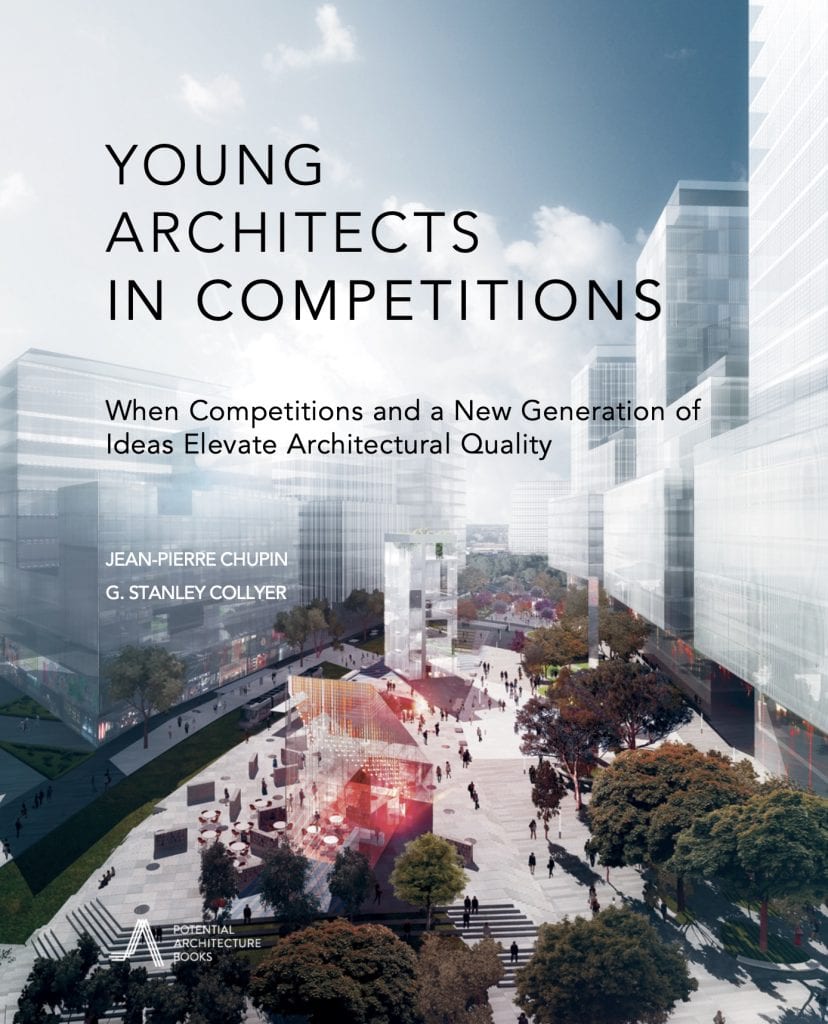

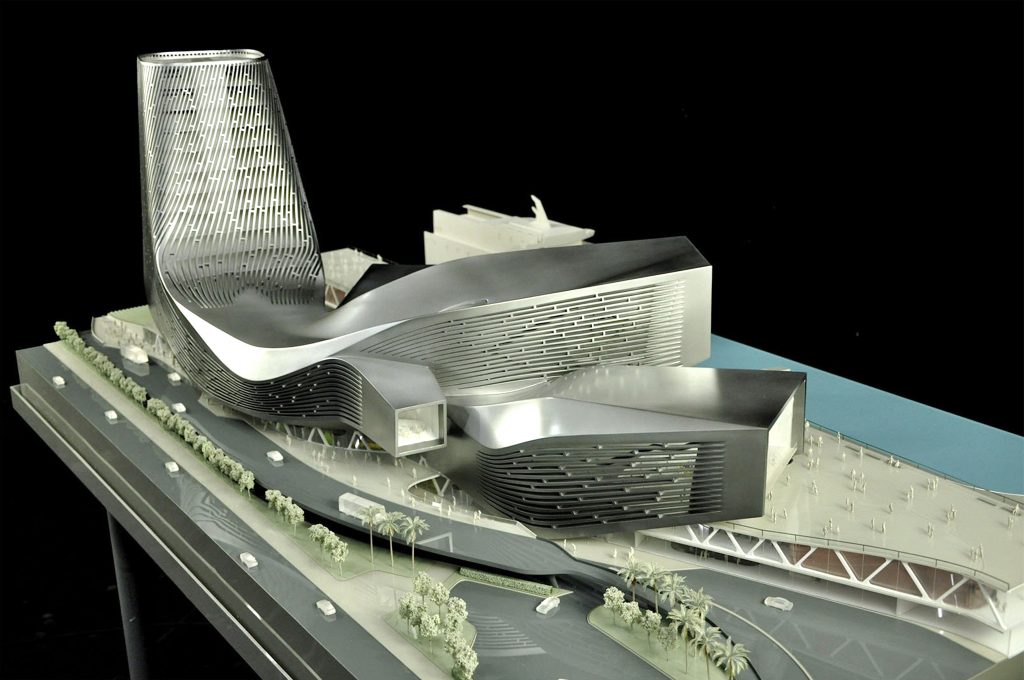

RUR model perspective – ©RUR

New Kaohsiung Port and Cruise Terminal, Taiwan (2011-2020)

Reiser+Umemoto RUR Architecture PC/ Jesse Reiser – U.S.A.

with

Fei & Cheng Associates/Philip T.C. Fei –R.O.C. (Tendener)

This was probably the last international open competition result that was built in Taiwan. A later competition for the Keelung Harbor Service Building Competition, won by Neil Denari of the U.S., the result of a shortlisting procedure, was not built. The fact that the project by RUR was eventually completed—the result of the RUR/Fei & Cheng’s winning entry there—certainly goes back to the collaborative role of those to firms in winning the 2008 Taipei Pop Music Center competition, a collaboration that should not be underestimated in setting the stage for this competition.

Read more…

Winning entry ©Herzog de Meuron

In visiting any museum, one might wonder what important works of art are out of view in storage, possibly not considered high profile enough to see the light of day? In Korea, an answer to this question is in the making.

It can come as no surprise that museums are running out of storage space. This is not just the case with long established “western” museums, but elsewhere throughout the world as well. In Seoul, South Korea, such an issue has been addressed by planning for a new kind of storage facility, the Seouipul Open Storage Museum. The new institution will house artworks and artifacts of three major museums in Seoul: the Seoul Museum of Modern Art, the Seoul Museum of History, and the Seoul Museum of Craft Art.

Read more…

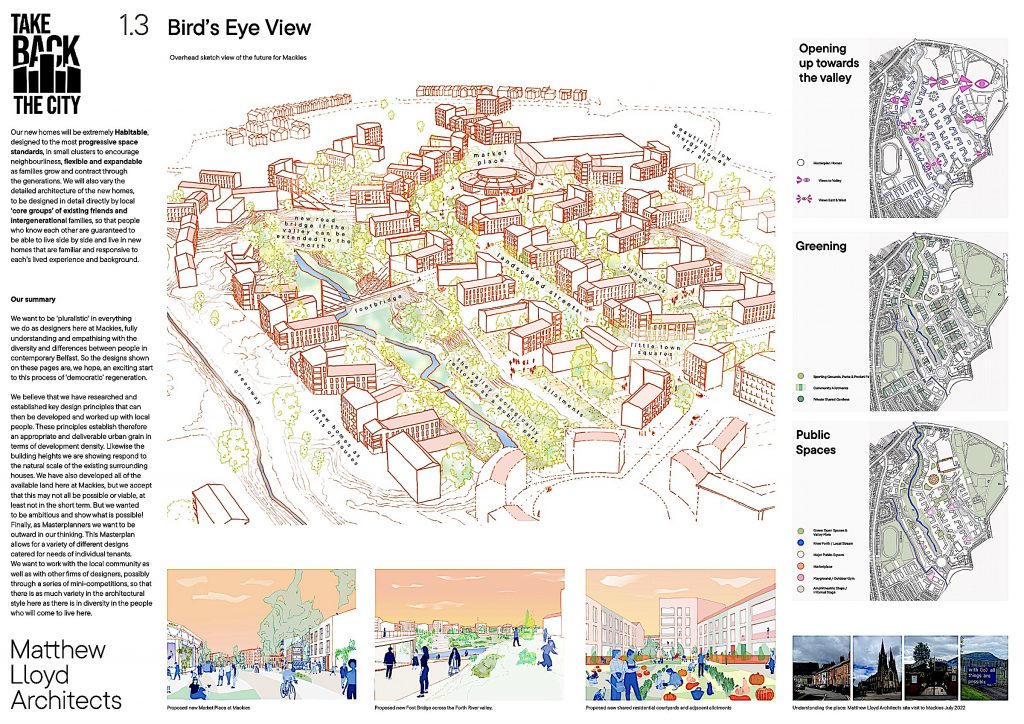

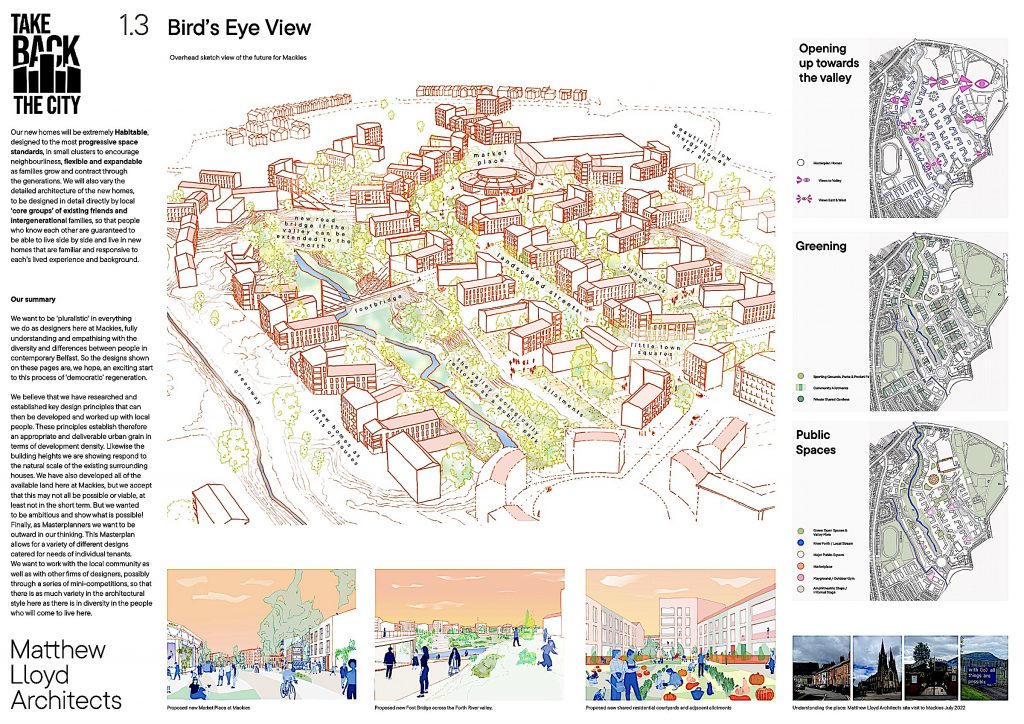

Belfast Looks Toward an Equitable and Sustainable Housing Model

Birdseye view of Mackie site ©Matthew Lloyd Architects

If one were to look for a theme that is common to most affordable housing models, public access has been based primarily on income, or to be more precise, the very lack of it. Here it is no different, with Belfast’s homeless problem posing a major concern. But the competition also hopes to address another of Belfast’s decades-long issues—its religious divide. There is an underlying assumption here that religion will play no part in a selection process. The competition’s local sponsor was “Take Back the City,” its membership consisting mainly of social advocates. In setting priorities for the housing model, the group interviewed potential future dwellers as well as stakeholders to determine the nature of this model. Among those actions taken was the “photo- mapping of available land in Belfast, which could be used to tackle the housing crisis. Since 2020, (the group) hosted seminars that brought together international experts and homeless people with the goal of finding solutions. Surveys and workshops involving local people, housing associations and council duty-bearers have explored the potential of the Mackie’s site.” This research was the basis for the competition launched in 2022.

Read more…

Alster Swimming Pool after restoration (2023)

Linking Two Competitions with Three Modernist Projects

Hardly a week goes by without the news of another architectural icon being threatened with demolition. A modernist swimming pool in Hamburg, Germany belonged in this category, even though the concrete shell roof had been placed under landmark status. When the possibility of being replaced by a high-rise building, it came to the notice of architects at von Gerkan Marg Partners (gmp), who in collaboration with schlaich bergermann partner (sbp), developed a feasibility study that became the basis for the decision to retain and refurbish the building.

Read more…

|