COMPETITIONS: you have been in both open and invited compe-titions—both as a juror and as a participant. Which type do you prefer and why?

RALPH JOHNSON: I think both are viable. For a young architect, open competitions are great, because they are not going to get invited. It’s a way for young architects to break into a bigger scope of work. It’s an oppor-tunity for someone who doesn’t have the experience in that particular building type to get into a new area.

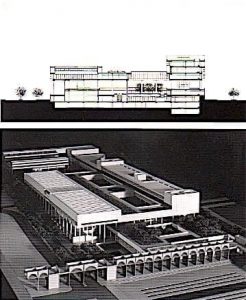

Shanghai Natural History Museum Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

An invited competition usually involves some kind of portfolio or resume of the firm’s work, and you usually get selected on experience in that particular building type. In the latter case, you are probably dealing with fairly extensive presentation requirements and a big outlay of money. It often also involves a couple of stages. If the compensation is adequate, which is usually six figures—$100,000-$200,000—it’s great. Most of the time, it’s inadequate. For the recent (Beirut Conference Center) competition, we did in Lebanon, it was $200,000, and that was enough to cover (our) costs. So there are benefits for both types of competitions.

COMPETITIONS: And as a panelist?

RJ: It’s much more difficult to jury the open ones because it takes longer. I was on the Astronaut Memorial jury, and there were over 600 entries. You normally don’t interview the architect; it’s single-stage. It’s more a process of winnowing out inadequate submissions—which is easy to do—and getting down to the ten percent after the first cut. In the case of an invited competition, you have five to ten submissions from very qualified firms. I think it’s good if you can actually interview firms and have a question and answer period. In an open competition, it’s almost inevitable that you wonder who is actually doing the project, how qualified the architect is. It’s hard to keep that out of your mind.

Shanghai Natural History Museum Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

COMPETITIONS: In other words, the presentation isn’t necessarily an indication of the qualifications of the designer?

RJ: I wasn’t on the jury in the case of the Vietnam Memorial, which was a famous competition. There were very sketchy charcoal drawings (by Maya Lin), which really didn’t indicate anything other than conceptual design capabilities. How could you possibly come to any conclusion of technical competence based on those drawings? You really have to read into it and assume a lot in terms of the person. In that case, of course, it was a great success as a non-complex building type. As a laboratory or something else, it’s a different story.

COMPETITIONS: There are a number of anecdotes concerning jurors speculating about the author behind a competition entry—the one in Paris resulting in the Grand Arch is an example. Richard Rogers, a competition juror, supposedly remarked to another juror, Richard Meier, that the author of what eventually turned out to be the winning design, “might be a nobody.” Meier reminded Rogers that, before Pompidou, he was a “nobody.”

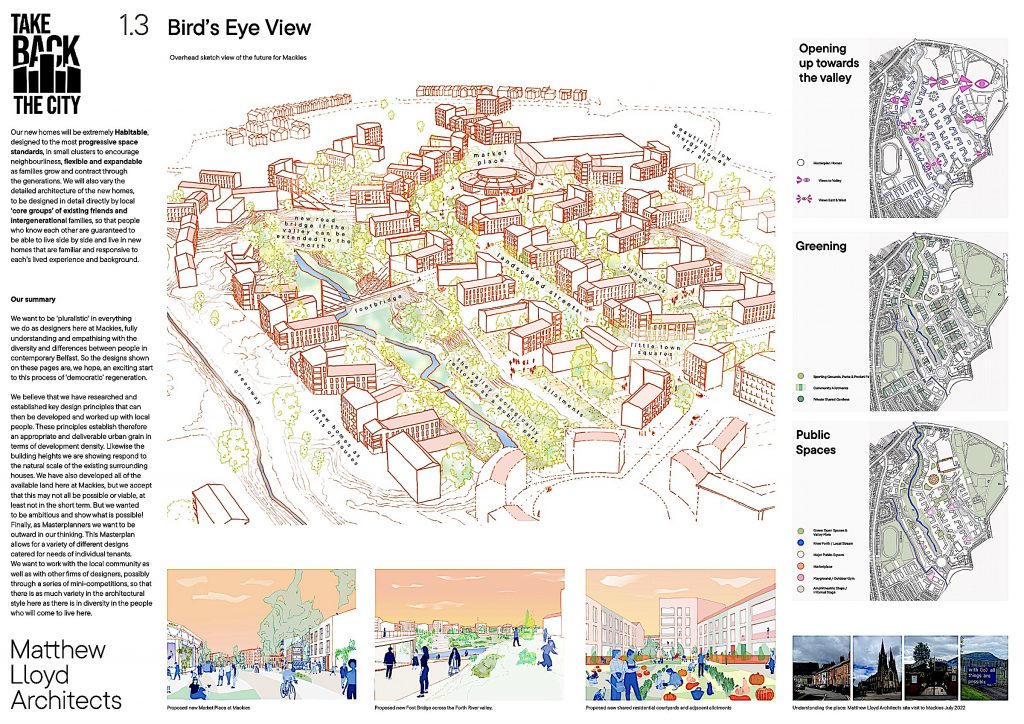

Pavlavi International Library Competition Finalist, Teheran, Iran (1977) Images: courtesy ©Ralph Johnson

RJ: When I did the Pahlavi National Library Competition—a one million SF library, I literally did it almost out of my kitchen. As one of the ten finalists, I was invited to Iran for the awards ceremony. At the time, I was in my late twenties and had done a very extensive presentation. They thought I was probably SOM or someone like that, because of the quality of the presentation. Part of the process was to visit the office of the winning firm, and had that been the case with me, it would have presented them with quite a surprise. This was shortly before I joined Perkins and Will. So that is the other side of the coin.

COMPETITIONS: You have served on numerous panels, one of the most recent being the University of Maryland Performing Arts Center jury. What advice could you give to people serving on juries for the first time?

RJ: Careful preparation for the jury is essential, including understanding the context, which is usually part of the process anyway—viewing the site. Also keeping an open mind about what the potential solution is…in the case of Maryland that was certainly the case. As with Maryland, you end up with a select group of 5-6 architects picked for differences of approach. Sometimes you don’t expect a certain solution from someone and get something different.

Contemporaine, Chicago, Illinois Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

Musée de Louvain la Neuve (Competition winner 2008, unbuilt) Images: courtesy Perkins and Will

COMPETITIONS: You were quite successful in the early competitions where your designs were premiated. The library competition in Iran and the Biscayne Housing competition (Miami) were two such contests. What career effect did those competitions have for you?

RJ: It had a very positive career effect, as I was thirty years old and had just moved back to Chicago. It was an opportunity to get some visibility and show my skills at solving very complex building problems. I had just started at Perkins and Will as a draftsman, and it gave people within the firm confidence that I could handle large building projects. It also got me some visibility within the city. Moreover, it was a good experience to: (A) solve a very complex problem; and (B) see how 500 other architects solve the problem. It gives young architects, even if they don’t win, a real opportunity for career development.

Univresity of Chicago Student Residences competition 2nd round finalist (2013) Image courtesy Perkins and Will

COMPETITIONS: This assumes that the competition sponsor does a catalog for distribution to the participants.

RJ: A lot of the bigger ones do.

COMPETITIONS: Recognition also may have its downside. In this case you become a potential participant in invited competitions, which usually turn out to be quite costly. How do you decide on the right one to enter?

RJ: Most recently, it has been competitions where we could get our costs fully covered—which is a fairly recent decision. We got into some fairly major competitions with very small compensation fees. It’s sort of an unknown quantity in terms of who the jury is. It’s just too big of a gamble. We made the decision that we wouldn’t do any more competitions because we couldn’t afford it. But then we got two offers for major projects where we could cover our costs; so we did them.

Los Angeles Federal Courthouse GSA Competition Winner (2001 – unbuilt) Images: courtesy Perkins and Will

COMPETITIONS: At some point, there was a realization that designing a good school building did not necessarily mean that it would automatically raise the educational level of the users. Isn’t the architect on a slippery slope here, because one should expect the building to enhance the learning experience? Maybe it’s not the building at all, but other factors. Why can’t a factory be a good school?

RJ: I was referring to the windowless, large, rectilinear high schools of the sixties with 3,000-4,000 students, many having internal classrooms. Much of that was purely economics to reduce the amount of initial cost and operating cost; and the impact of that on education was to create sterile environments, hardly conducive to learning. I think the architect can produce a framework for education, but obviously someone has to do the educating of the students within that framework. My personal philosophy is—especially in the case of a high school—is to look at a certain campus model, creating a kind of microcosm of the community, and express that in the architecture. There are so many aspects to education, which are not taught in the classroom, but in the corridors and outer spaces where people interact. That’s just as important as what you learn in the classroom. It’s almost like a small town or small society.

COMPETITIONS: Currently the word “context” is used in a very loose and indiscriminate manner by many architects to describe their work. You use this term also. What does ‘context’ mean for you? Is it something to do with texture, style, volume, grid, or reference to another architect? What does it mean to you?

Perry Community Educational Village, Perry, Ohio (1990-1995) Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

RJ: It’s a wide-ranging term. It could be cultural; it could be immediate physical context; it could be stylistic if you are adding directly on to a building. When you are designing, it could be that the context is a negative context, and that you improve with a change. There is always some context within which a building exists. Maybe context became overused in the Posti-Modern era—it was always assumed that you should be self-effacing and match what is next door, no matter what is occurring there. Context has to be more of a critical kind of a process. Look at the context, and then you have to determine what your attitude toward it is, whether you have to build on the context, or whether it needs to be improved or transformed. So there has to be a more proactive attitude. The problem is that context became a rote kind of approach.

COMPETITIONS: In Chicago one of the most recent stylistic references is the Evanston Public Library, an obvious reference to Frank Lloyd Wright. Orland Park (Civic Center) also suggest you were referring to Wright.

RJ: As far as context in Orland Park, it was how much the context needed to be improved. That building has nothing to do with architecture in the immediate surroundings, which is a commercial environment. It does draw upon the Prairie School of architecture, which is a local tradition of architecture. But I wouldn’t say it is a literal interpretation of the Prairie School; it’s more of a transformation. To put a literal Frank Lloyd Wright building from 1910 there would be almost like Disneyland. Besides a transition to a modernist context, it also had to have the sense of a public building.

COMPETITIONS: My sense was that this building (Orland Park) needs a more dramatic approach from the main road, such as an allee.

Orland Park Community Center, Orland Park, Illinois (1987-89) Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

RJ: That’s exactly what I did, if you look at the master plan we did. We went beyond the scope of the project. One of the problems with that site is that the center of Orland Park—its main street—is LaGrange Avenue, which is a commercial strip. There was this zone, which separated our site from this main street, and the building needed to be plugged back into the main street with some type of axial arrangement. At the time, Orland Park was going through a whole mater plan process for that area, leaving the suggestion of an allee to plug it back into the main street, also with buildings reinforcing it on each side. It still could happen. The power of architecture is the individual building, which can begin to suggest things beyond its immediate site. It’s the building as a transforming device, as a clue for the future.

COMPETITIONS: Your University of Illinois School of Architecture has recently been completed. What would you want students to learn from this building?

RJ: First of all, the building contains the disciplines of architecture, landscape architecture and urban planning, three different disciplines housed in buildings scattered around campus. The main purpose of the building was to provide interdisciplinary activities between these three departments, which didn’t occur before. The building itself as a concept employs principles that are key to those three disciplines. We spent quite a lot of time analyzing the history of the master plan and went back to the Platt plan of the 1920s, when the military axis was suggested. We realized that our site was at the critical intersection of the main north-south and east-west axis proposed by Platt. The building really begins to suggest the definition of those two axes, as part of the project was to literally redesign the quad and actually begin to build the east-west axis, which rally never was built. So the building is a very important urban object on the campus as it begins to define urban patterns and act as a device, which forms as basis for the campus.

It also involves landscape architecture in the sense that the landscape is carved to create this courtyard and penetrates into the atrium, the inner space. As for the architecture itself, the outside is short of an interpretation of Georgian architecture—it’s a very background building—brick with punched windows. The interior courtyard is much more modernist in character, and you begin to see what the structure and mechanical elements of the building express. It’s almost a building in section. You can see how the building is held up and how the mechanical systems service the interior spaces of the building. It’s an educational tool in that sense.

Contemporaine, Chicago, Illinois Photos: courtesy Perkins and Will

COMPETITIONS: Building in Chicago has its own special challenge, especially when one has only to look out the window to view some of the best architecture in the world. Doesn’t it set standards, which anyone might find rather daunting to match?

RJ: I would say that it is an interesting challenge to be aware of the layering, historical layers of the city, going back to the Burnham plan and the other masterplans, and all the layering of the various styles in the city, and not just the obvious ones—not only the Chicago School, but the Second Chicago School, the deco buildings, the classical buildings. When you design in the city of Chicago, you have to really not respond to the cliché of what Chicago architecture is, but the fundamentals of what Chicago is about: honesty in architecture and the relationship between program and basic economic concerns which the early Chicago buildings did so well. Mies’ buildings too are the combination of solutions to pure economic needs of a developer turned into a poetic vision of urban architecture.

COMPETITIONS: What was your most challenging project?

RJ: It probably would have to be the Morton International building (Chicago). The most obvious reason was the technological challenge of building a 37-story highrise over an operating rail line. It was not only the pure construction problems, but getting the grid of an office building to work with the grid of columns (necessitated by) the pattern formed by the tracks and adjust all those structural conditions in the building and then expressing them in the architecture.

There was one area of the building where we couldn’t sink foundations; we had to hang fourteen stories of the building off the roof, which turned that into a major aesthetic asset for the building. Also, that site was really never planned as a building site. It was a leftover site, not a traditional loop infill site, and it was never quite clear how the street wall should look. It required a little of the vision of how this building might fit into what might happen in the future along the river. I think the site will strengthen as the area to the north is filled in.

Morton International Building, Chicago, Illinois (left)

Photo: courtesy ©Perkins+Will

Northwestern Medical Research Center 2014 Competition Winner (right)

Imges: ©Perkins+Will

COMPETITIONS: The Chicago Navy Pier was a great opportunity, probably a lost one judging form the results. What happened there?

RJ: We entered that competition, and there were some interesting proposals, especially Helmut Jahn’s entry. But we never knew who the jury was, or how the decision was arrived at. That is a classic case of how a competition shouldn’t be run.