with Jerzy Rosenberg

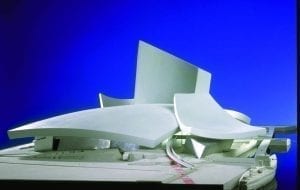

Bremen Philharmonic Hall Competition, Bremen, Germany – First Place (1995)

COMPETITIONS: Among the leading architects in the world, you may be unique in that everything you have built came about exclusively through competitions. Consequently it would be interesting to hear you view on competitions, and in particular whether you think it is still a viable form for young architects’ participation in the making of architecture.

LIBESKIND: It is a great form to work with; I probably would never have had any practice without competitions. But the nature of competitions is changing. In fact, now that the competitions are being globalized, they are becoming less of a form and forum. With globalization and the consequent bureaucracy, comes the opposite effect— a fragmentation and regional control by power brokers. It is now less possible to have an independent choice by competition because there are more networks which are involved.

COMPETITIONS: What is the earliest competition that you recall participating in?

LIBESKIND: I would say that was the IBA, the City Edge Project in 1987.

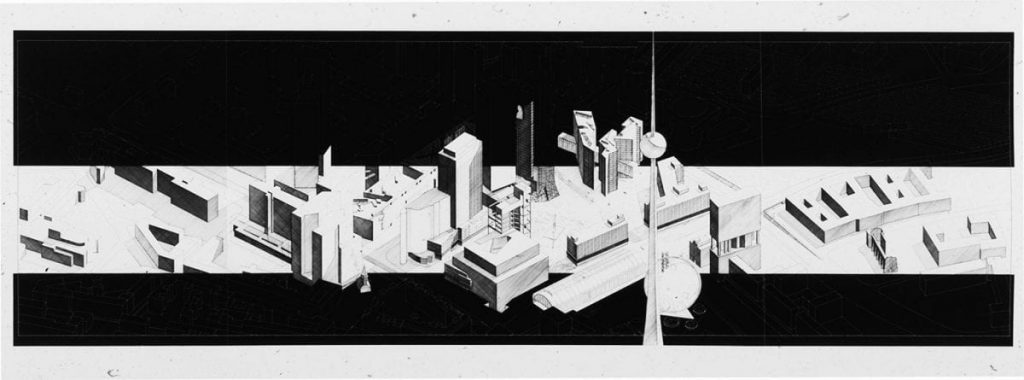

Alexanderplatz Urban Design Competition, Berlin, Germany – Second Place (1993)

COMPETITIONS: That’s one of the competitions that you have won which for one reason or another have not been built. Any regrets?

LIBESKIND: Well, of course, I would have been pleased to be able to design and construct the City Edge idea. However, even though some of the competitions I have won or came in second, have not been built, whether it’s City Edge or Potsdamer Platz or Alexander Platz, I do feel that they have had another influence on the direction on how people perceive the substance of what is to have happened. And they have contributed to the public architectural discourse both in Berlin and outside and in fact are continuing to do so until now. So, not winning a competition does not always mean not winning. Sometimes losing a competition is more important than winning it, in terms of setting a dialogue or a vector of popular understanding of what is at stake.

Actually, I do not regret a single unbuilt competition, because I never enter them in the first place with the sole interest in winning. I enter them in order to explore new areas of architecture and to contribute a new consciousness in terms of program and form.

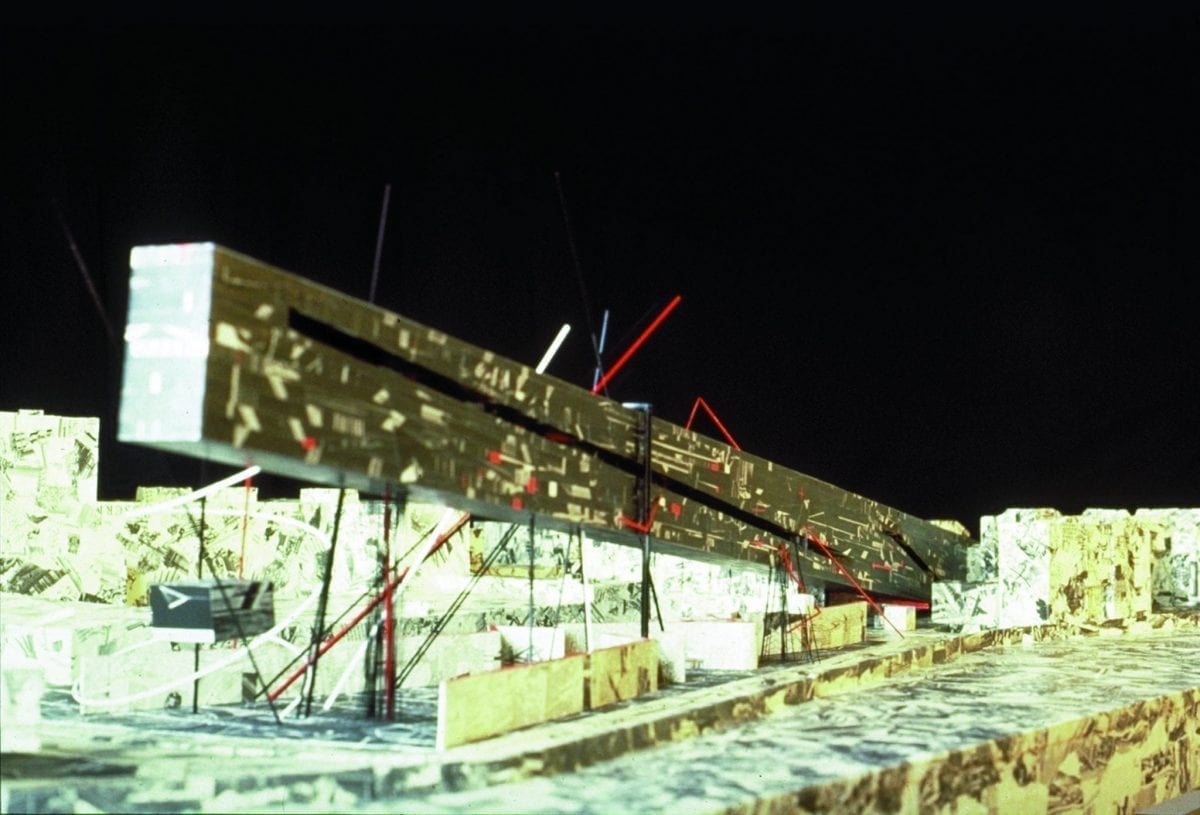

IBA City Edge Competition, Berlin, Germany – First Place (1987)

COMPETITIONS: Is that for example, the case with Sachsenhausen?

LIBESKIND: Yes, Sachsenhausen and the City Edge. The City Edge is a good example. This winning competition entry was not built for political reasons, because of the unification of Berlin. The site suddenly became no longer available, but still, the City Edge project was the first model for a different approach to building, other than closing the block structure in Berlin. That paved the way for different projects, like the Jewish Museum, which also did not close the block and did not reestablish the typology of 19th Century Berlin. Sachsenhausen was totally different—a competition which I lost because I refused to follow the competition brief. I did get an Honorable Mention for reminding the people of the history of that site, but initially after refusing to build housing or a police station on the site of the first Nazi Concentration camp, I was disqualified. Well six years later, and hundreds of trips to Oranienburg to speak to the citizens and administrations, we received the commission to do the planning for the site based on our competition proposal—a real victory of people over political manipulation.

COMPETITIONS: The aspect about the Berlin Museum that you just brought up about the kind of connection and continuation…

LIBESKIND: It’s not the Berlin Museum; it’s the Jewish Museum

COMPETITIONS: It’s the museum with many changing names. The Jewish Museum then. It raises a question of formal continuity, one that was brought up by one of my students. He found, a third year project, I believe, done by you at Cooper Union, a housing project, which he was convinced was the seed, the germ of the Jewish Museum project at least in the formal sense.

LIBESKIND: That reference has been brought to my attention, but I wouldn’t say that was a conscious act on my part. It was not something I was aware of. Well, in retrospect it might be related but not consciously. That is to say that the Jewish Museum is not a formal project.

COMPETITIONS: How then would you describe the Extension of the Berlin Museum with the Jewish Department, which was the original name of the competition?

LIBESKIND: Yes, that was the original name, then it became The Extension to the Berlin Museum with the Jewish Museum; then the Jewish Museum of the City Museums; then the Jewish Museum in the City Museums; and finally the Jewish Museum, Berlin. In one sense it was an urban project. As I indicated previously, it questioned the then prevailing desire for the recovery of the 19th Century Berlin block structure, a desire, by the way, expressed in terms of the most gross and objectionable nationalism. I saw the scheme as a condensation of the positive, cultural forces of the city inscribed into the Museum through the linkage of addresses of well known Germans and Jews torn apart by the actions of Nazi criminals. The spirit in which I designed the Museum is part of me as a person and a Jew, born to survivors of the Holocaust. From the proposal, which was just lines on paper, to the building which is now completed, I was unwaveringly committed to making a museum which would portray in an uncompromising way the tension and struggle of the Jewish presence in Berlin. A presence not only of the Einsteins, the Schoenbergs, the Benjamins or the Liebermans but all those nameless Berliners inextricably bound with the identity of the city.

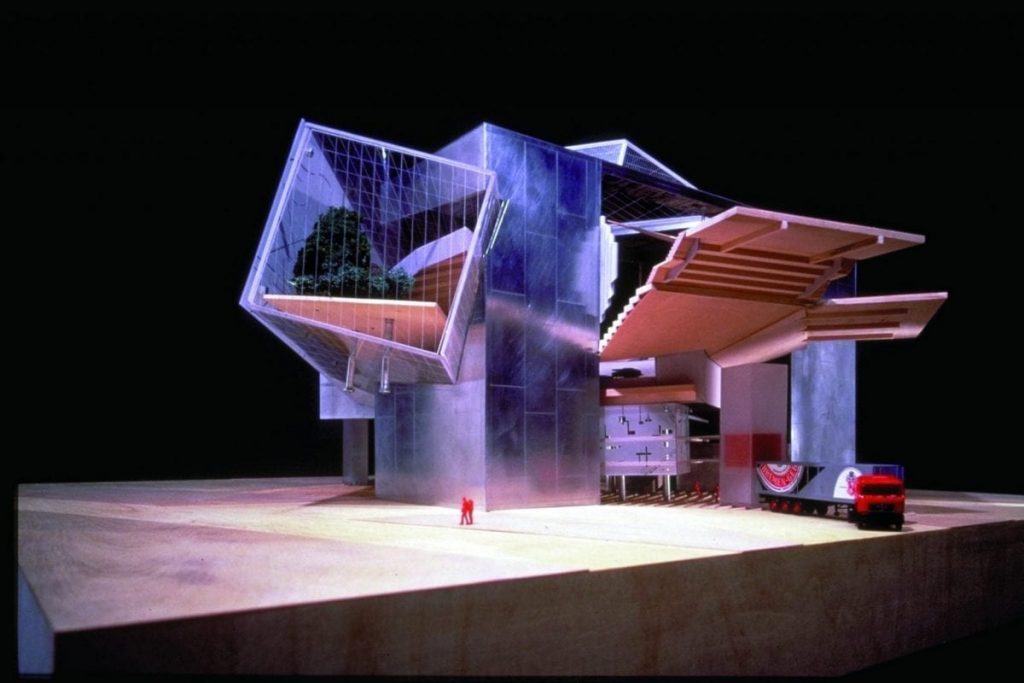

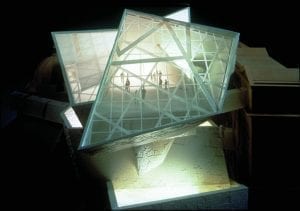

Imperial War Museum North Competition, Manchester, England – First Place (1997)

COMPETITIONS: The Jewish Museum opened last January ten years after you won the competition. How would you describe your experience and the changes that took place during construction?

LIBESKIND: Whatever changes which have taken place in the design over the last 10 years were ones which were part of the organic evolution of the design, rather than changes imposed from the outside. As such, the design has remained without any overt compromises.

COMPETITIONS: Let’s return to the sources of your work: how would you evaluate the relationship of your education, particularly the specific and unique education that the Cooper Union afforded in the 60’s. Do you see any continuity any resonance in your work?

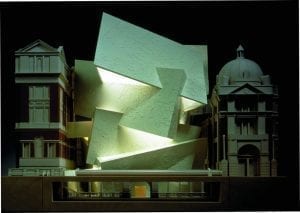

Victoria & Albert Museum Competition, First Place (1996)

LIBESKIND: Well, Cooper in the 60’s was a school which constituted a form of resistance to ongoing ideas, a kind of a revolutionary base. People like Gwathmey, or Eisenman or Meier or Hejduk or whoever was teaching there at that time, were not at that point successful practitioners, but kind of contra the scene, in resistance to the common sense of what was going on in the world of practice. So that on the educational level it was not about forms or style or anything of that sort, rather it was about a notion that architecture is not some sort of a service to clients but an idea which goes beyond what is “the right response.”

COMPETITIONS: And a parallel question would be how does your teaching experience find its way onto your work?

LIBESKIND: Well, sure, teaching is an opportunity to break away from the mold established by the profession, therefore any project that has any merit, challenges professional truisms with responses to real issues and it is not something that is just a rote individual response. So teaching and learning are absolutely primary in the sense that each project that one undertakes is a beginning.

COMPETITIONS: In much of your work, I recognize the presence, the echoes, sometimes literally, sometimes poetically, of the drawings that you have done before you started building. Often these drawings: the Chamber Works and the Micromegas, have been described as “not architecture” – I have always thought otherwise and was wondering, from the present vantage point, how do you view that particular period of work.

LIBESKIND: To have called them “not architecture” is to have offered an absurd label. In fact what is architecture but drawing? And, if you take Palladio’s drawings and compare them to his buildings you discover in the latter a traditional practice, while the drawings develop a discourse which is actually oblivious to particular problems and is independent of the specific commission. So I would say my drawings: Micromegas, Chamber Works function in my work in the same way as Palladio’s or other architects basic constructs work for their practical projects.

Jewish Museum Competition (First Prize 1989; completion 1998)

Images courtesy ©Daniel Libeskind; upper right, ©Stanley Collyer

COMPETITIONS: I have one more question on the Jewish Museum; it’s a material question could you explain the cladding.

LIBESKIND: Well, one way to put it is that I did not have the resources of my good friend Frank Gehry to use titanium. I did not have that kind of budget, so I used a very vernacular material, zinc, which will age, oxidize and actualize in six or seven years, and in ten years will acquire a patina reminiscent of the Baroque and vernacular roof-scape and window scape of the traditional Berlin. Perhaps this blue-gray zinc will become a background of the city, which will become in itself a background for the very dramatic cuts of the windows. This material, I believe, is harmonic with the weather conditions of the city and its light – quite different from the red, yellow and blue buildings that have sprung up as result of abstract experiments. Zinc is a material that has originally been inspired by Schinkel’s advice that a good architect working in Berlin should use as much zinc as possible in Berlin and I have certainly used more of it than anyone else!!

COMPETITIONS: Recently you won two competitions in England. Considering the nature of your work, that seems a radical departure for the tradition obsessed Brits. What are those projects? Why do you think you have won? And how is the work progressing?

LIBESKIND: The two projects being built are The Extension to the Victoria & Albert Museum—”The Spiral” and the Imperial War Museum, north in Trafford, Manchester. Why and how did I win? Good question. Perhaps I won because I was not prejudiced by the so-called ‘common sense’ wisdom regarding what can be built. Somehow both projects struck a resonance with the histories of these places as institutions and provoked a wide public debate about the function of architecture in the 21st century. I have realized that the idea that traditions are static are false since traditions themselves are in the process of transformation. What is clear is that even, or especially in competitions, one has to have what I would term a ‘learned ignorance,’ a willingness to deal with the future and not become mired in the past.

Both projects are progressing at different rates. The IWM is on an incredibly fast track and beginning construction in December with the opening scheduled for the Commonwealth Games in 2001. The V&A, having received planning permission at the end of last year is to be realized by 2004.

COMPETITIONS: You have participated in two competitions for synagogues in Germany, one in Duisburg and one in Dresden. This seems to be a particularly difficult subject in a very problematic condition. How did you confront this?

LIBESKIND: In fact building synagogues in Germany is not difficult at all. What I had to deal with, however, was the very conservative nature of the congregations here. All the congregations are either Conservative, Orthodox or ultra-Orthodox which meant that the Synagogue had to be planned around the separation of men and women.

I just don’t believe in that and so I immediately got into trouble with the non-architectural parts of the jury. Hence my second place win in Duisburg and my loss in Dresden. Perhaps one day I shall get a commission from a more open minded congregation!!

COMPETITIONS: Memorials of various kinds have been a frequent subject of competitions both in Europe and the US. What is your view on memorials?

LIBESKIND: Memorials are certainly extremely problematic. As Robert Musil pointed out already in the 1920’s, building a Memorial is the best way of forgetting. This has not changed. Among the recent Memorial competitions in Germany I have seen banal and simplistic ideas which neither deal with the issue to be memorialized nor create a new consciousness. It takes an exceptional scheme to transcend the reality that the only persons who visit memorials are those who do not need to…

COMPETITIONS: Your past competition projects dealt, mainly, with cultural objects. Places of work seldom come up for competitions. You did win a competition—the Tenth Muse—for a government center/office complex in Wiesbaden Germany. How did this competition differ from others and how did you resolve your architectural concerns?

LIBESKIND: No projects are non-cultural. Everyday workplaces and dwellings do indeed have a cultural significance and demand a response no different from so-called cultural icons.

.