Book Review By Paul D. Spreiregen

Photos: Paul Spreiregen

On any given day visitors to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington may number in the hundreds, sometimes the thousands. Immediately upon its dedication in November 1982 it became and has remained one of the most visited sites in our nation’s capitol. Extending tranquilly across a tree bordered meadow near the Lincoln Memorial, its power as a work of tribute stands among the great memorials of any time or place. It is an American icon. Visitors to the memorial may know that a college student designed it in a nation-wide design competition and that the selected design was the subject of great controversy. Little else about its creation is known or need be known by a typical visitor. The memorial speaks for itself, honoring the nearly 58,000 Vietnam veterans who died in the war and by implication the millions of others who served. As a work of public art it honors memory and service admirably. For those who wish to probe further, to understand how the memorial came to be, as well as its historical and artistic significance, there is more than ample literature. The totality of books, articles and papers numbers in the many hundreds. Most of these deal with a particular aspect of the memorial, and have been written by journalists, scholars and critics. In addition, there are several recollections written by participants in the memorial’s creation.* A comprehensive account was first published in 1985, “To Heal a Nation,” written by Jan C Scruggs, a wounded Vietnam combat veteran and the founder of the memorial project, along with author Joel L Swerdlow. It is an easily read and moving account, describing the effort from its inception in March 1979.

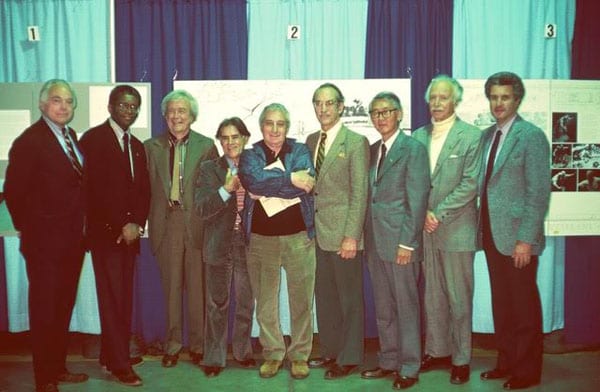

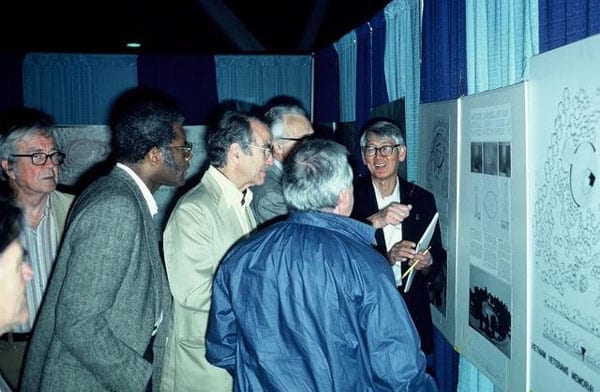

A second and more detailed account has now been published, also authored by one of the key participants in the memorial project, Robert W Doubek, an intelligence officer in Vietnam, who worked on the project alongside Scruggs and the late John H Wheeler III from the start. His account, the subject of this review, is a companion piece to that of Scruggs and Swerdlow. Any reader interested in the story of the memorial will quickly find his or her way to both books—as well as numerous articles on the Internet. The Scruggs-Swerdlow book is an inspiring tale about an ordinary guy realizing an extraordinary vision in the face of formidable odds. Doubek’s book is a cautionary tale —very cautionary. But before examining it, a brief chronology of the memorial’s creation is helpful. The full story can be portrayed through five basic and two adjunct phases: Phase 1, Genesis March 1979 to July 1 1980, a period of about 14 months. The project began with the inspired idea of Jan Scruggs to create a memorial to the nearly 58,000 American dead and by inference the millions who served in the Vietnam War. This phase includes the creation of a sponsoring group, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF), the beginning of fund raising, the Congressional authorization for a memorial on the Mall, and signing the authorizing legislation into law by then President Jimmy Carter. Doubek, Wheeler and a number of other highly dedicated Vietnam Veterans participated in this effort, as did many volunteers. Phase 2, Memorial Design July 28 1980 to May 1 1981, a period of 9 months. This phase began with the planning of a nation-wide design competition open to all American citizens age 18 or over. To assure its viability the entire competition process was closely coordinated with four federal agencies that oversee memorial designs in the capitol. The competition was the largest held up to that time, attracting 1,432 design submissions. The winning design was selected by eight distinguished and highly respected design professionals. That design, the work of Yale undergraduate, Maya Lin, was widely acclaimed when initially presented to the public. Phase 3, Preliminary Design Approval May 27 1981 to August 6 1981, a period of 9 weeks. In little more than two months, preliminary design approval was obtained from the four approval agencies—the Joint Committee on Landmarks, the National Park Service, the Commission of Fine Arts, and the National Capitol Planning Commission. These rapid approvals, even though preliminary, were absolutely vital to the continuation of the work towards realization, not the least for fund raising. Phase 4, Design Development, Controversy, and Final Design Approval August 1981 to March 11 1982, a period of about 7 months. A design-build team was created. It was comprised of a Washington architectural firm (the Cooper-Lecky Partnership) with Lin as consultant, and an accomplished construction firm (the Gilbane Building Company). The design was further developed and further approved. Construction documents were also prepared and completed during this phase. In the fall of 1982, however, an intense and well-organized opposition campaign to block the memorial design began. This opposition received wide press coverage and threatened to destroy the entire undertaking. A compromise was reached in which the VVMF agreed to add a figurative statue and flagpole. The Secretary of the Interior then issued a permit to start construction. ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ Phase 5, Construction and Dedication March 16 1982 to November 13 1982, a period of about 8 months. Construction began immediately upon authorization. Particularly challenging was the arrangement and inscription of 58,000 names on granite panels imported from India. Construction concluded just prior to a dedication ceremony on November 13 1982. The ceremony was attended by thousands of Vietnam veterans, their families, and families of the deceased. It included an emotional parade of veterans and a recitation of the names of the nearly 58,000 dead at the National Cathedral. November 13 1982 thus marks the realization of the memorial, slightly more than two and a half years from the start of the competition, an interval unprecedented for such an undertaking. Immediately upon its dedication, it became a national icon. But the work was not over. A statue group and flagpole, agreed to in the compromise, were yet to be added, but not without further difficulty. Phase 6, the Statue and Flagpole March 1982 to November 11 1984, a period of over 2-1/2 years. In accord with the compromise agreement sculptor Frederick E Hart was commissioned to create the three-soldier figure group that stands at the western or Lincoln Memorial approach to the memorial. A flagpole was erected nearby. All the while opposition to the memorial continued, ever threatening but gradually waning. Phase 7, A Memorial Statue Group to Nurses Killed in the Vietnam War 1983 to Nov 11 1993, a period of about 10 years. Diane Carson Evans, a nurse who had served in Vietnam, formed the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Project, a entirely separate organization, to honor the memory of eight nurses killed in Vietnam and again, by inference, some 265,000 women who had served. The memorial consisted of a statue of two nurses tending a wounded soldier. It was created by sculptor Glenda Goodacre and dedicated on Nov 11 1993. Its location is to the east of the Vietnam Memorial. Phase 8, An Underground Interpretive Center 2003 to 2015, a period of about 12 years Finally, an underground visitor center on an adjacent site, an idea initiated by Jan Scruggs back in 2003, was approved and is now under construction. As an educational facility, it is there for those who were not yet born during the Vietnam conflict.

Aerial view of post-competition presentation model

Save for the Women Nurse’s memorial and the interpretive center, the Scruggs-Swerdlow book tells the story in 175 pages, with an additional 239 in which the names of the 58,000 are listed alphabetically. They also included a very useful listing of the names of everyone who participated without mention of rank or station. Doubek tells the story in just over 300 pages, including a very helpful index, but without citations or references for the numerous events described. Many more illustrations as well as a time line or chronology would also have improved the book. Further, the Scruggs-Swerdlow book, with all its components, is centered on Vietnam veterans and the effort to honor their service, separating that from the rightness or wrongness of the war. (The VVMF constantly emphasized that the memorial was not to be a political statement in any way.) In contrast, Doubek’s book centers on his own role, the project as he experienced it. What, then, has he added? The simple answer is much greater detail, all of it varying in degrees of interest.

Like Scruggs-Swerdlow he wrote about the origin of the idea, its evolution from idea to authorizing legislation, fund raising, the competition, the approval agencies, construction, public relations, celebrity supporters, the various dedication ceremonies, the compromise agreement to add a statue, even his private struggles. He wrote about the many people involved, his recollections of what they did and what they said. He provides numerous details not found in other sources. One example is the background of an accusation by the memorial’s opponents that one of the jurors had communist affiliations. The most surprising revelation in Doubek’s narrative is the frequent mention of animosities within the VVMF organization itself, sometimes severe. Anyone who has ever been part of any organization has of course witnessed interpersonal difficulties, but the ones he describes would wreck a good many of them. Few are the participants who, in his account, come away unscarred or unblemished. The “enemy” was both within and without. Unfortunately, the book is not without gratuitous and at times demeaning characterizations, needlessly disparaging several of the people who contributed significantly. This is not to say that the story is without heroes. Doubek acknowledges the vital support of then Senators Charles “Mac” Mathias Jr. of Maryland and John W Warner of Virginia, who guided the effort through its most perilous times. They were not alone.

Maya Lin and her role are also described. In the public mind she is a deserving hero, a lone youth standing up to the oppressive bureaucracies of male controlled Washington. Doubek’s book, as well as other sources, mention the story of her design in part—its origins in a design studio at Yale and the important role of her instructor, Andrus Burr, her fellow students, and two visiting architectural critics. All helped shape her concept, originally an architectural pun mocking the “domino theory.” Lin’s behavior in her early days in Washington is a further matter, also described in the book. She was understandably zealous to maintain the integrity of her design, as was everyone else involved. But unfamiliar with the procedures for gaining both public support and design agency approvals, all of which intensified in the days following the competition’s conclusion, she became mistrustful of the VVMF. This lead her to complain about what she regarded as her mistreatment to others around town, including the American Institute of Architects. Her actions seriously threatened to undermine a still fragile enterprise by discrediting the VVMF. What, then, does all this detail amount to? A history, or in this case as much a memoir, can and should be more than a recollection of events. It can be an interpretation of those events, a broader understanding of them, what they demonstrated at the time and how they might guide in the future. The book would have benefited considerably by going beyond a recitation of numerous incidents by seeing in them larger and instructive lessons.

There are two that might well have been included. Both are related to the design competition and are mentioned here for readers interested in competitions, designers and potential competition sponsors. First is the role of the earlier mentioned design approval agencies—the Joint Committee on Landmarks, the National Park Service, the Commission of Fine Arts, and the National Capitol Planning Commission. These agencies can be formidable obstacles confronting proposals for memorials and many other types of public projects. Frustrating and cumbersome as these agencies may appear, and indeed as they may sometimes be, the opposite is the case. These agencies hold the power to proceed with or deny public projects in Washington. Their approvals, earned incrementally—from preliminary design to final design—have the force of law. In protecting the public realm they also protect the integrity of the designs they oversee. Without that system there would be chaos. Without that system the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Lin’s design, would not exist— with or without the two added statue groups. While this is implicit in the text it is important enough to have warranted far clearer exposition. Second, more complex and more significant, is the role of the design competition. Conducted rigorously and in accord with long proven practices, it included a fully professional jury and produced a design that was quite simple, easy to explain, harmonious with its site, unobtrusive, easy to build and easy to maintain. In short it was a design that was relatively easy to approve. The competition process, Phase 2, took about nine months, the ensuing approval process and the formation of a design-build team, Phase 3, a little more than two additional months. As the design process was relatively straightforward, granite processing and name inscriptions notwithstanding, construction documents could be completed in about six months. While this was proceeding, and starting in October 1981, severe and threatening opposition mounted. As mentioned, negotiations in the following months resulted in an agreement committing the VVMF to add a sculpture and flagpole, the design to be developed. This compromise gained final approval to begin construction. Most important, this six or so month period, sufficient to prepare the needed construction documents and obtain construction approval also meant that the period of intense opposition efforts was limited. This in turn was key to avoiding one of the most effective methods of stopping any project, prolonged death by delay. Had the competition been poorly run; had it not had a fully professional jury; had the design been something more conventional or more complex; had the design not merited quick preliminary approval; had the design-build team been unable to complete the construction documents in a brief time; in short, had not the entire design procurement, approval and development process been so brief, the memorial may never have come to fruition. That’s the larger lesson of the competition. It was at the heart of the entire enterprise, all the other component efforts notwithstanding. One has only to compare this history with that of any of memorial effort before or since to appreciate its significance, remembering that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was a far more precarious undertaking. It was an extremely sensitive and divisive subject—the war, the veterans, and finally the memorial design. Had such broader perspectives supplemented the many particulars of Doubek’s “inside story,” the book would stand as more than what is essentially a personal memoir. Granted that the particulars of all memorials are unique, the lessons of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial project, seen in fuller context, could inform such equally deserving memorial undertakings as the future may present.

*Books or papers written by those who participated in the creation of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in the order of their publication: ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

“Letter to the Secretary of the Interior James Watt” Grady Clay Dec 1 1981 Available on-line. ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

“Process for Selecting Design for National Vietnam Veterans Memorial” Jan C Sruggs Dec 14 1981 Available on-line “Vietnam’s Aftermath: Sniping at the Memorial” Grady Clay Landscape Architecture magazine March 1982 Pgs 54-56 ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ To Heal a Nation – The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Jan C Scruggs and Joel L Swerdlow 1985, (and subsequent anniversary editions) Harper and Row 414 pages, illustrated, including a 239-page appendix of the names of the nearly 58,000 dead

Making the Memorial

Maya Lin Nov 2, 2000 The New York Review of Books ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

“Interview with Grady Clay” Jan 25 2003 Interview by James Ward Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Boundaries Maya Lin 2006 Simon and Shuster 224 pages, illustrated ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

“The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Design Competition, Washington DC, 1980-81” Paul D Spreiregen Dec 2007 DC Center magazine Pgs 47-50, illustrated Available on-line ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

“The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Design Competition, Washington DC, 1980-81” Paul D Spreiregen 2010 An academic symposium paper published in “The Architectural Competition, Research Inquiries and Experiences”, Ronn, Kazemian, Andersson, editors AXL Books, Stockholm Pages 578-600, illustrated Available on-line ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

Designing for Remembrance: An Architectural Memoir William P Lecky 2012 LDS Publishing 171 pages, illustrated

A 25th anniversary publication, sponsored by the Vietnam veterans Memorial Fund though not written by one of the participants, is: ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ

The Wall: 25 Years of Healing and Educating Kim Murphy 2007 M.T. Publishing Company 208 pages, illustrated

Paul Spreiregen is a Washington based architect. He was the professional adviser for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Design competition, serving from July 1980 through August 1981, when the design concept obtained preliminary federal agency approval. ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ