Is a museum collection only as good as the architecture that houses it? With the glut of contemporary museum design producing world-class buildings for even the most mundane of collections, that seems to be the consensus of the age. Yet there is no doubt that when a museum collection is distinguished enough, it can benefit from a well-designed container.

The Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, Germany boasts just the sort of outstanding collection in need of a better home. Since 1995, the museum has been housed in an art museum on Theaterplatz that incorporates Clemens Wenzeslaus Coudray’s 19th century classicist Kulissenhaus. As a piece of architecture it is not a bad building, but it is certainly a laughably incongruent style for one of the most influential modernist schools of the 20th century. Fortunately, this mish-mashed arrangement was always intended to be temporary, and this summer, an intriguing museum design was selected as a permanent home through the New Bauhaus Museum Competition.

Despite being the birthplace of the celebrated school, Weimar is not normally thought of as a pilgrimage destination for the Bauhaus. That distinction would invariably go to the school’s second location in Dessau. After all, this is the location of Bauhaus founder and director Walter Gropius’s iconic and seminal school building, from which he, his distinguished faculty, and brilliant students produced their most enduring and recognizable works of architecture, furniture, and industrial design. And as the location of the school’s most prolific period, Dessau boasts one of the largest concentrations of Bauhaus-designed buildings anywhere. The legacy is easy to see.

The Weimar Bauhaus left behind a much smaller, more difficult to see legacy. The school itself was located in the former School of Arts and Crafts, an Art Nouveau building designed by Henry van de Velde in 1904. And the Bauhaus itself was not prolific in producing architecture in its early years. In fact, the Haus am Horn, built by students as part of a 1923 school exhibition, is the only real architectural contribution found in Weimar, and even that is somewhat off the beaten track.

But even with this lack of built evidence there is no denying that the Weimar era, lasting from 1919 to 1925, was an important, formative period for the Bauhaus. This was the Bauhaus where Gropius and a diverse, respected cast of artists, architects, and theorists crafted the beginnings of a revolutionary movement in design; the Bauhaus of Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Theo van Doesburg; the Bauhaus that underwent a crucial shift from the early Expressionist leanings of Johannes Itten towards the more practical rationalism of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. By the time increasing antagonism from Weimar’s Nationalist government prompted a move to the more sympathetic and supportive political environment of Dessau, the Bauhaus boasted a fully formed design philosophy that made possible the landmark work to come. The Bauhaus of Weimar left behind a legacy of international significance.

This legacy is encapsulated in the city’s Bauhaus Museum, the second largest collection of Bauhaus artifacts in the world. The museum boasts a permanent exhibition of more than 300 objects that were produced in the Weimar school, and offers great insight into the early years of the Bauhaus. Original works by founding director Walter Gropius and celebrated faculty such as Johannes Itten, Paul Klee, Gerhard Marcks, and Lyonel Feininger are on display, as well as a wide collection of student work, most notably Marcel Breuer and Alma Siedhoff-Buscher. Exhibited together, these pieces illustrate the diverse, highly creative, ever-evolving nature of the early Bauhaus.

A collection of this caliber deserves a world-class container, a place in which it can produce a significant visual impact upon the built landscape of the city, rather than hiding behind the deceiving facade of a 19th century Classist building. Thus the Bauhaus Museum Competition was organized and implemented to find a more architecturally compatible home.

The Competition

Launched in July of 2011 by the Klassik Stiftung Weimar (Weimar Classics Foundation) and the City of Weimar, the New Bauhaus Museum Competition invited architects to take part in a multi-stage open design challenge. The first round asked participants to locate an appropriate site for the museum within the complex urban fabric of Weimar and propose an evocative conceptual design. The response was incredibly positive, with 536 architects (the large majority European) submitting highly compelling entries.

In November 2011, the jury decided upon twenty-seven teams to advance to the second round, where conceptual designs were to be fully developed into detailed, feasible buildings. In March 2012, an international jury chaired by Professor Jorg Fierich of Hamburg awarded two second-place and two third-place prizes, along with three honorable mentions. They were:

- Shared 2nd Prize (40,000 Euros each): Johann Bierkandt – Landau, Germany

- Shared 2nd Prize (40,000 Euros each): Architekten HKR (Klaus Krauss and Rolf Kursawe) – Cologne, Germany

- Shared 3rd Prize (30,000 Euros each): Prof. Heike Hanada with Benedikt Tonon – Berlin, Germany

- Shared 3rd Prize (30,000 Euros each): Bube/ Daniela Bergmann – Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Honorable Mentions (9,666 Euros each): Karl Hufnagel Architekten, hks Hestermann Rommel Architektenn, menomenopiu architectures/Alessandro Balducci

A final stage required the four prize winners to refine their designs according to the feedback of the jury. A final review in June awarded the final commission to German architects Heike Hanada with Benedict Tonon.

The Winning Entry

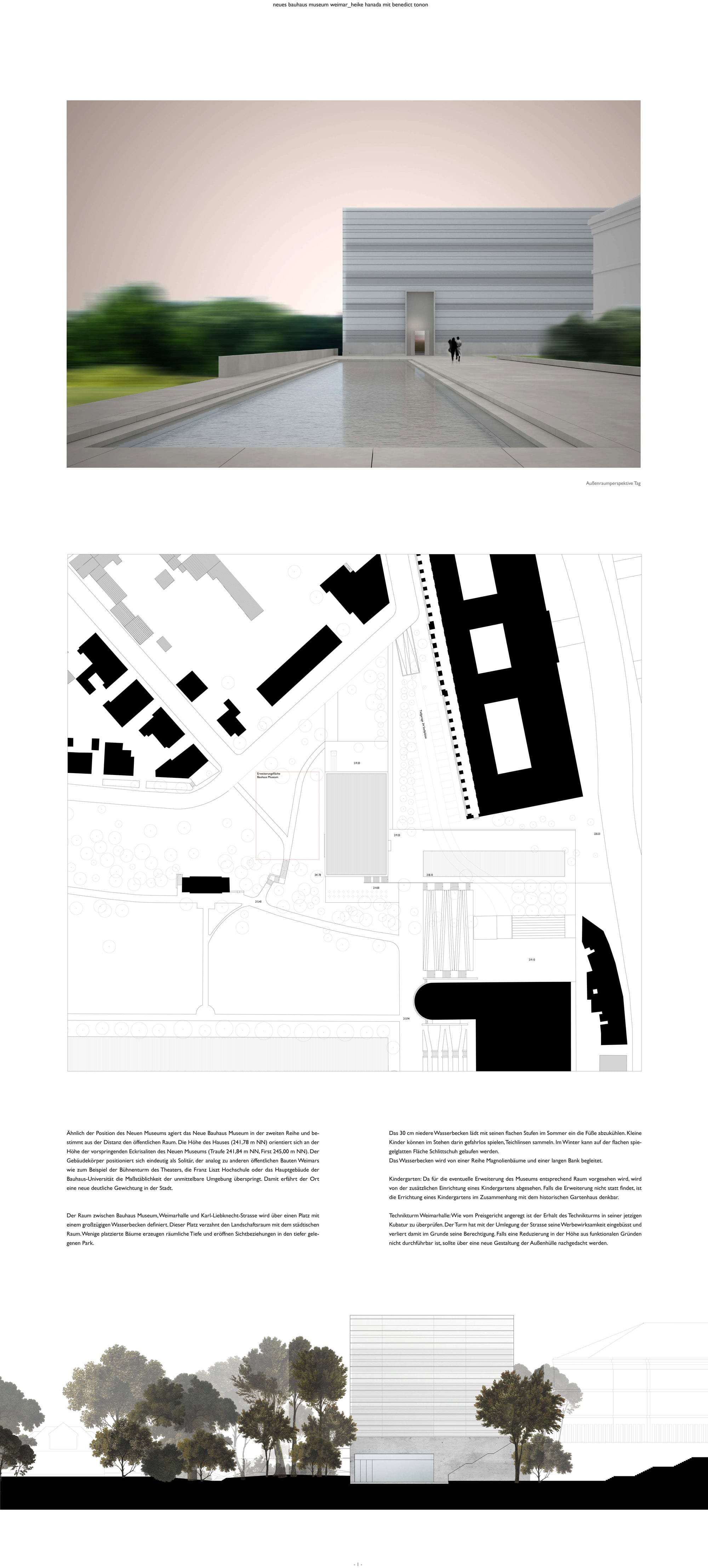

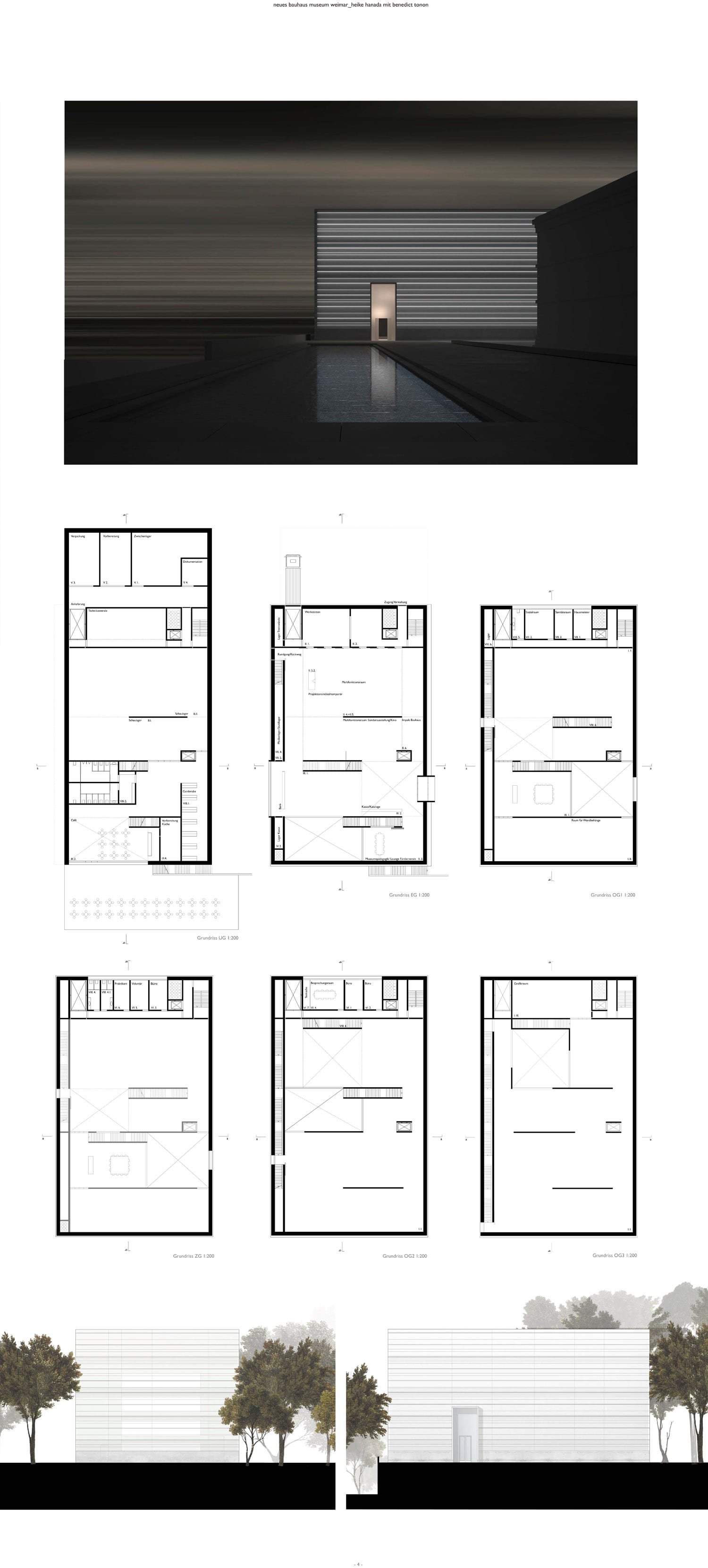

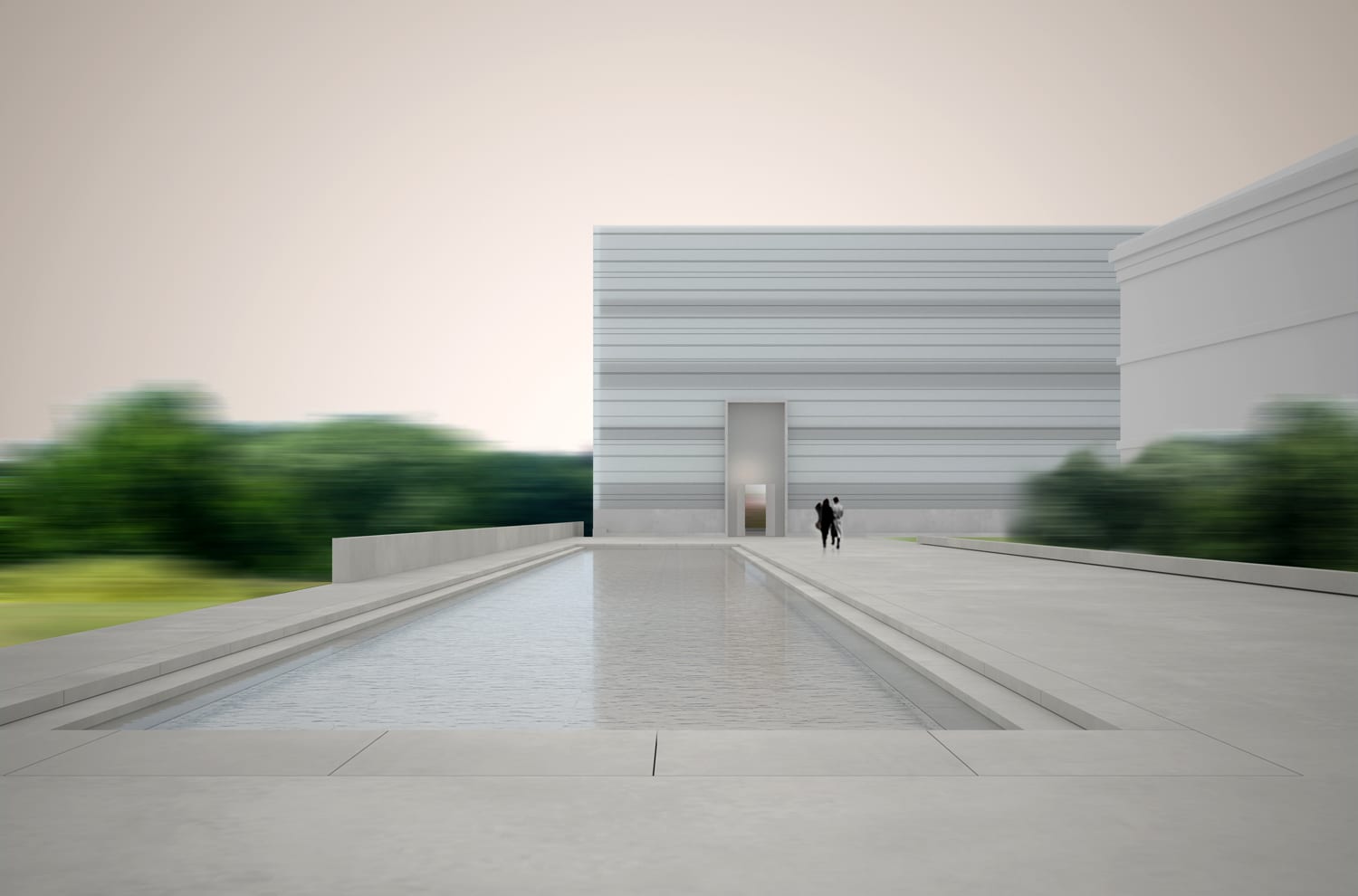

It comes as no surprise that the aesthetic sensibilities of the Bauhaus informed the design schemes of virtually all of the finalists. Clean, rectilinear volumes are prevalent, as is minimalist detailing, rational structure, and a modernist material palate of steel, glass and concrete. The winning design by Hanada is no exception to this trend, but it sets itself ahead of its peers with its sense of refinement. It is a design of strikingly bold simplicity, elegant minimalism, and evocative materiality.

Set on a park slope, the building is positioned as a freestanding “solitary object,” a single, rectangular volume intended as a strong iconic form. Flanking the museum, an oblong reflecting pool on a simple raised plaza is used as a device to “mesh” the built landscape into the surrounding urban context. The pool is shallow, only 30 centimeters deep, allowing children to use it in the summer and for ice-skating in the winter.

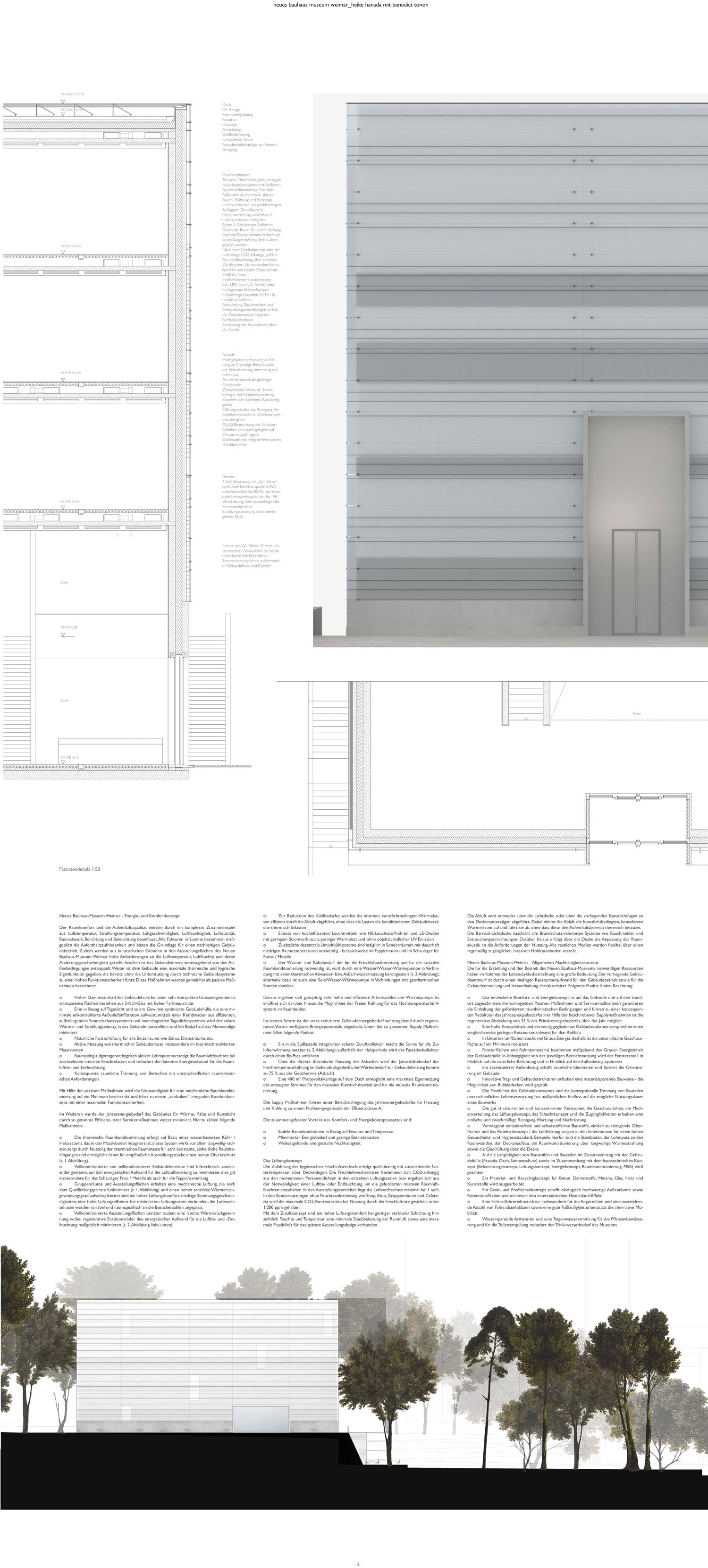

The building represents a “monolithic sculpture in space,” facilitated by a façade with alluring transparent qualities. Over a monolithic shell of cast concrete, opaque satined glass panels affixed with metal brackets freely float over the building surface, punctuated irregularly by a screen of horizontal etched black lines. At night, narrow strips of OLED foil placed behind the glass will illuminate the facade with an ethereal glow. With the exception of an exposed concrete base, this layered glass skin covers the entire museum volume, diffusing the hard lines of the monolithic building volume and creating an intriguing relationship between solid and transparent masses.

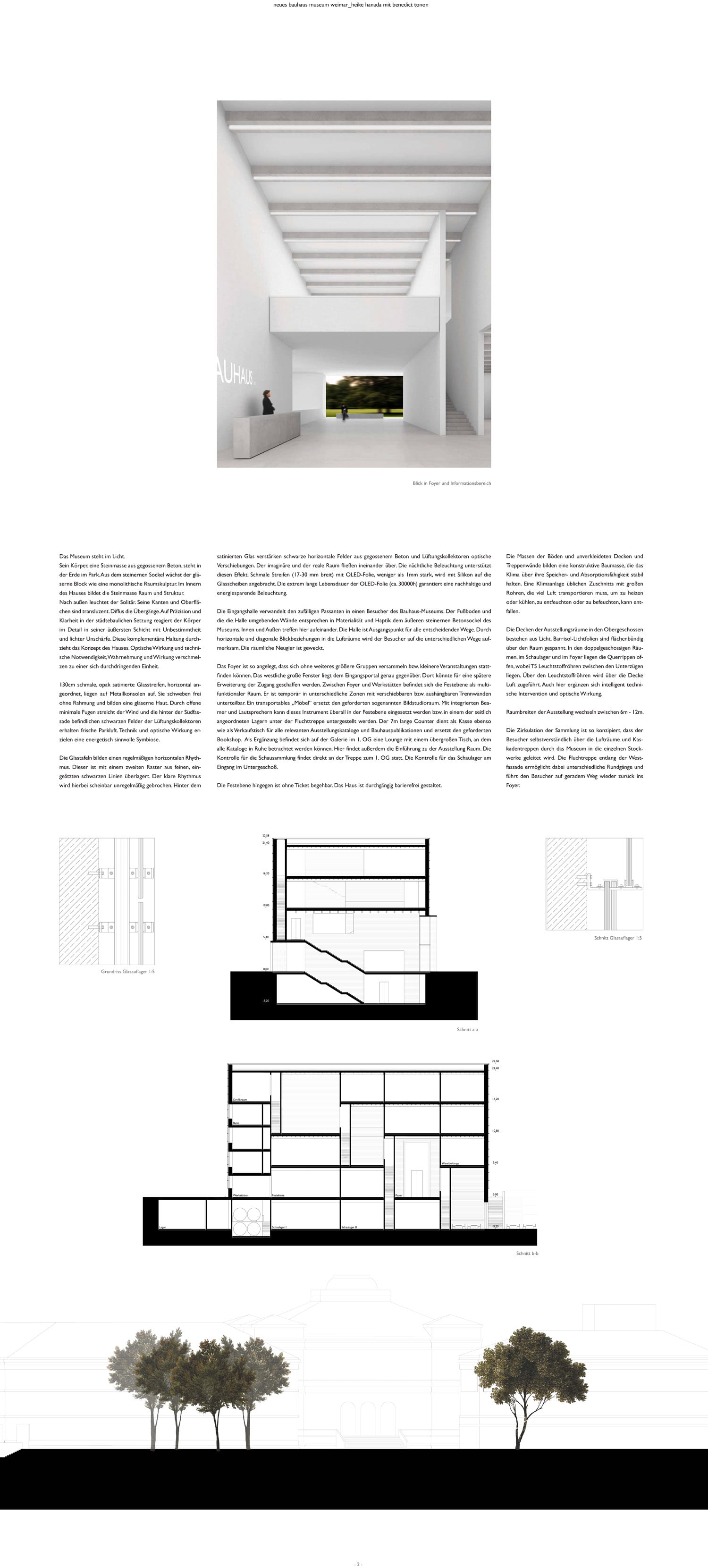

The interior takes a similarly simple approach, its six floors featuring generous open gallery spaces that appealed to the jury for their flexibility. A white, minimally detailed interior allows the objects and exhibits of the Bauhaus collection to take center stage.

Successful minimalist design is hard to pull off, particularly on such a large scale. And such a design is made or broken by its level of detailing. Heike Hanada and Benedict Tonon, architects as well as professors, are both thoughtful designers with an inspired attention to detail and inherent academic rigor, so it is with an admirable but not unfounded faith thar the the jury selected such a strikingly yet deceptively simple design. (Hanada is not new to design competition accolades. In 2007, she won first prize for an expansion of the Stockholm Public Library: see Competitions Volume 17, Number 4. Unfortunately, this project was put on hold in 2009.)

Interestingly, the winning design was initially positioned in third place after the March 15 jury session. At the time, the museum volume was clad only in textured white concrete – a minimalist cube that seemed a bit too simplistic. Jury feedback and an extra few months of refinement allowed for Hanada and Tonon to turn a good project into a great one. The result is a daringly simple design rendered exceptional through its refined expression of tectonics and careful attention to craftsmanship.

With an exciting design selected for the New Bauhaus Museum and a grand opening set for 2015, Weimar is poised to have its important Bauhaus legacy pushed to the forefront of the city. Upon congratulating the winners of the competition, Thuringian Minister of Culture and Foundation Board Chairman Christoph Matschie said it best: “The Bauhaus is now finally being provided with a fitting location at its Weimar cradle. Once again, the Bauhaus will become a symbol of reawakening in the time to come. The building of the museum is providing an important impulse for the entire development of the city of Weimar.”

Finalist: Johann Bierkandt – Landau, Germany

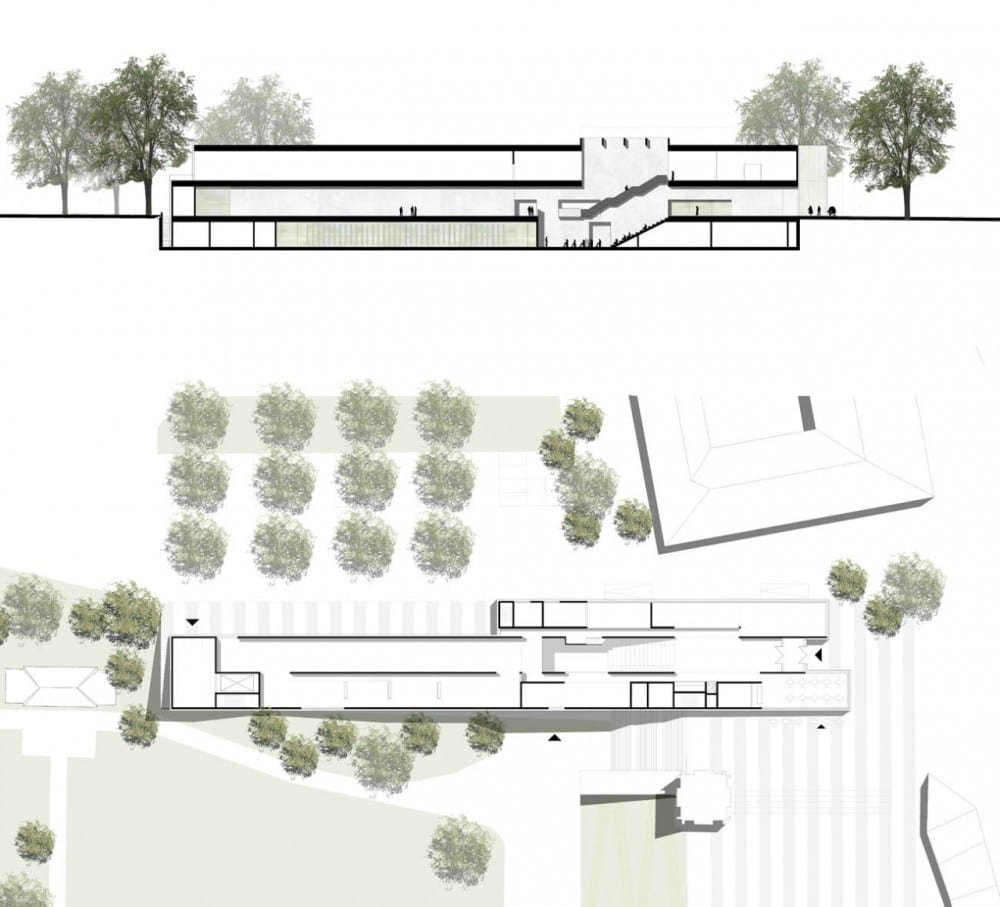

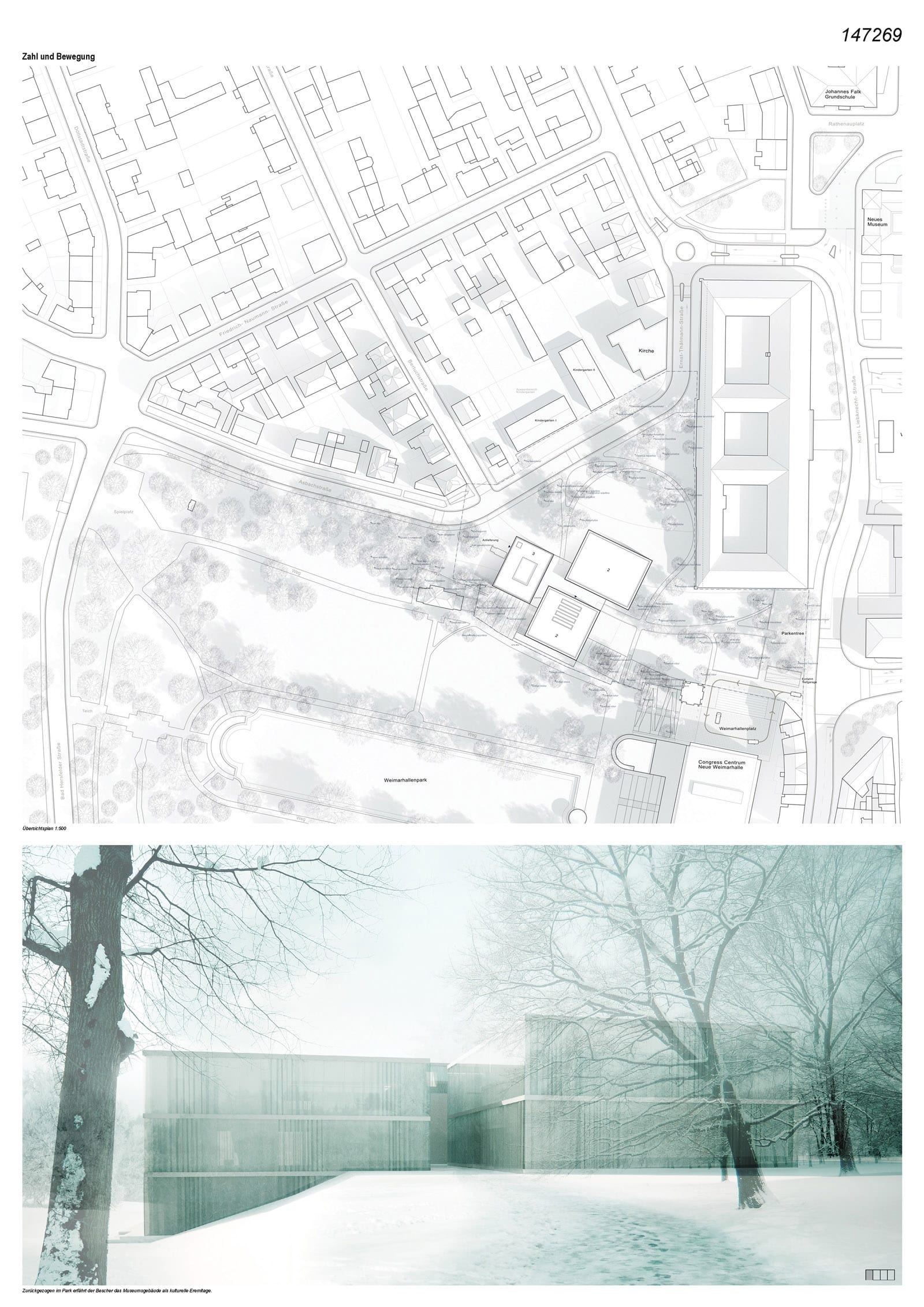

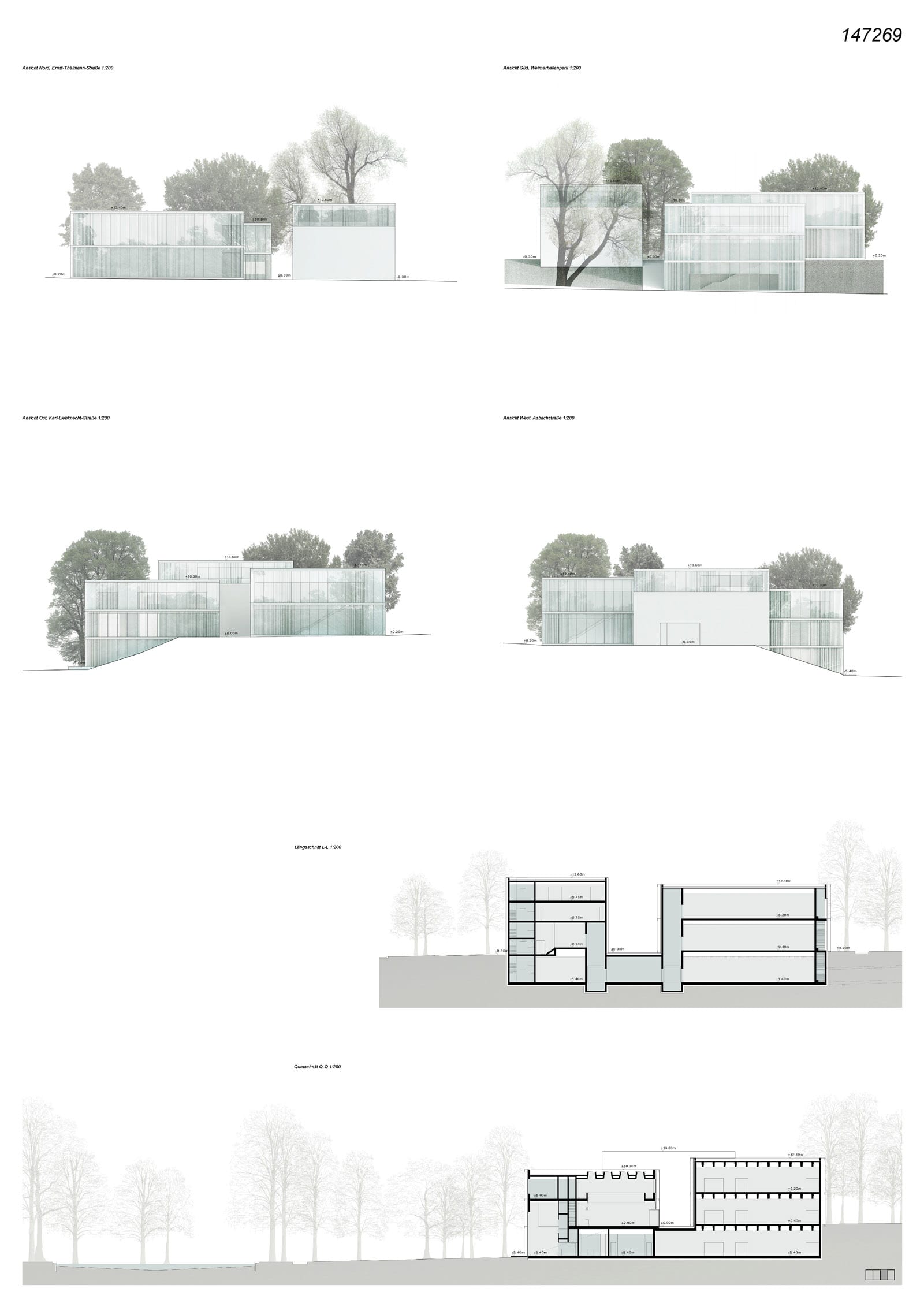

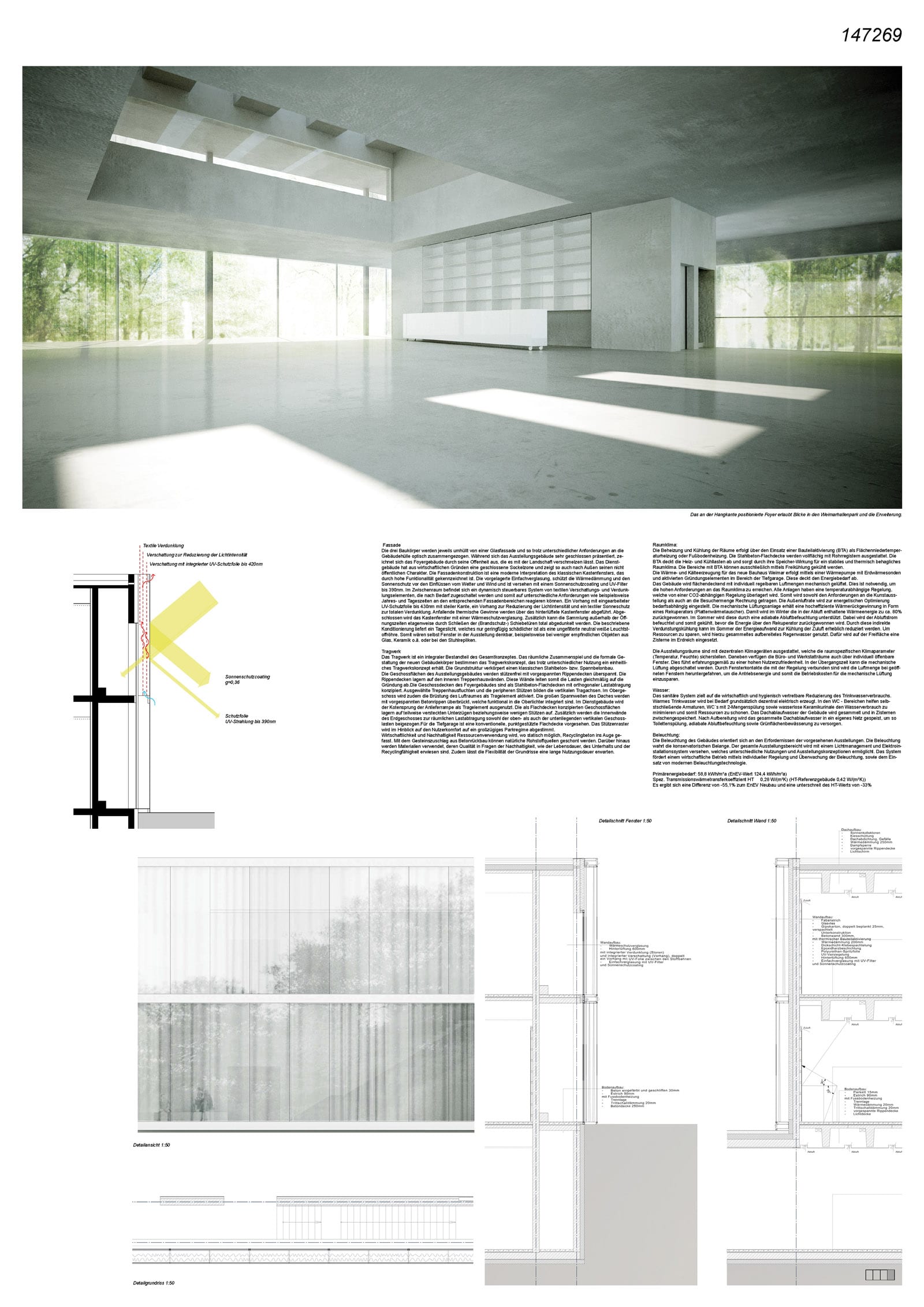

Jury report: “The proposal by Johann Bierkandt (Landau) develops the figuration of a small-scale, urban museum ensemble, distinctly separate from the large-scale Weimarhalle and the Thuringian State and Administrative Office nearby, as well as the adjacent residential buildings. The proposal doesn’t aim to present a compact museum, but rather includes additive structural elements, which play on the differentiated educational concept of the Bauhaus. The jury expresses its admiration for how the proposal integrated the museum with the Weimarhallenpark.”

Finalist: Architekten HKR (Klaus Krauss and Rolf Kursawe) – Cologne, Germany

Jury report: “The proposal by the Architekten HRK (Klaus Krauss and Rolf Kursawe, Cologne) provides excellent access to the park. The distinctive form of the museum makes an even stronger impression in the urban setting and is characterized by the cleverly staggered arrangement of the elongated structures. The proposal is also impressive in terms of its interior design qualities. The central interior space creates a distinctive, independent and attractive flair for the New Bauhaus Museum.”

Finalist: Bube / Daniela Bergmann – Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Jury report: “The museum design proposed by Bube/ Daniela Bergmann (Rotterdam) features a composition of three translucent structures which lie somewhat removed in a newly won park environment. This concept also consciously sets itself apart from the dominating habitus of the large former Gauforum and the neighboring Weimarhalle.”

Honorable Mentions

During the first phase of the competition, the jury awarded three Honorable Mentions to projects that offered “outstanding individual aspects and valuable contributions for the construction of the museum,” but were deemed unfeasible for actual implementation.

Of particular interest is the scheme by Rome/Paris-based MenoMenoPiu Architects. Their museum is conceived as a large open square sheltered by a roof of translucent, overlapping horizontal planes, providing a flexible space allowing for various activities and functions.

Honorable mention MenoMenoPiu Architects – exterior rendering