by Stanley Collyer

Once the destination of large passenger liners and freighters, ports such as Manhattan and San Francisco are now more likely to be the site of entirely different activities. Cities have discovered that waterfronts lend themselves to all kinds of recreational activities: instead of large ships, we may now find tennis courts, museums and restaurants located on those once abandoned piers. The conversion of waterfronts to other uses is hardly limited to North America. In the run-up to the 1984 Barcelona Olympic Games, Oriel Bohigas was asked to devise a plan, which included the redesign of the Barcelona waterfront. It turned out to be an attractive destination for locals and tourists alike and may have represented a subliminal moment in the minds of the Spanish architects who recently won the recent Kaohsiung Maritime Cultural & Popular Music Center International Competition in Taiwan. Recognizing the potential of this post-industrial site, the Kaohsiung authorities chose to stage a competition as a vehicle to facilitate the transformation process — with the stated intention of injecting new energy into an outdated waterfront location.

The competition site, a half-circle 11.89 hectares stretch of waterfront frontage in the port district of Kaohsiung, includes an ambitious programmatic wish list: a large exhibit & performance area, some small exhibit & performance areas, an outdoor exhibit & performance area, a pop music exhibit area, a maritime cultural exhibit center, a ferry terminal & passenger service center, a pop music industry center (incubation center), a music art & maritime technology commercial area, scenic landmark, and administration area. Including a required floor area of 71,000m2, the total budget for this project is projected at US$137M.

As has often been the case with Taiwanese competitions, this one was also run in two stages, with the first stage being open/anonymous. However, during this first stage, the competition adviser was confronted with an unanticipated change in the process: the client added five of its own jurors to the panel just five days before the submission deadline. The adviser felt this was an unfair imposition on the competitors, who had entered, based on the assumption that the jury panel had been well-established without any significant changes. He then prevailed on the client to suspend the competition until the issue could be resolved. Finally, the issue was laid to rest, as the client agreed to stick with the original choice of ten jurors.

In the meantime, to accommodate the concerns of the competitors, they were given two options by the adviser—to stick with their original submitted entry without having it returned or, to have their entry returned with the possibility of fine-tuning it and then resubmit it. Needless to say, most competitors stuck with the first option.

With the later re-start of the competition and the conclusion of the first stage, five finalists were advanced to the second stage (including local collaborating firms). They were:

and Charles C. Yen, Architect – Taiwan

The 10-member jury which adjudicated the submissions was international in character, with five from Taiwan and five high-profile international architects from abroad. The latter were:

The competition coordinator was architect Barry Cheng

The Winning Design

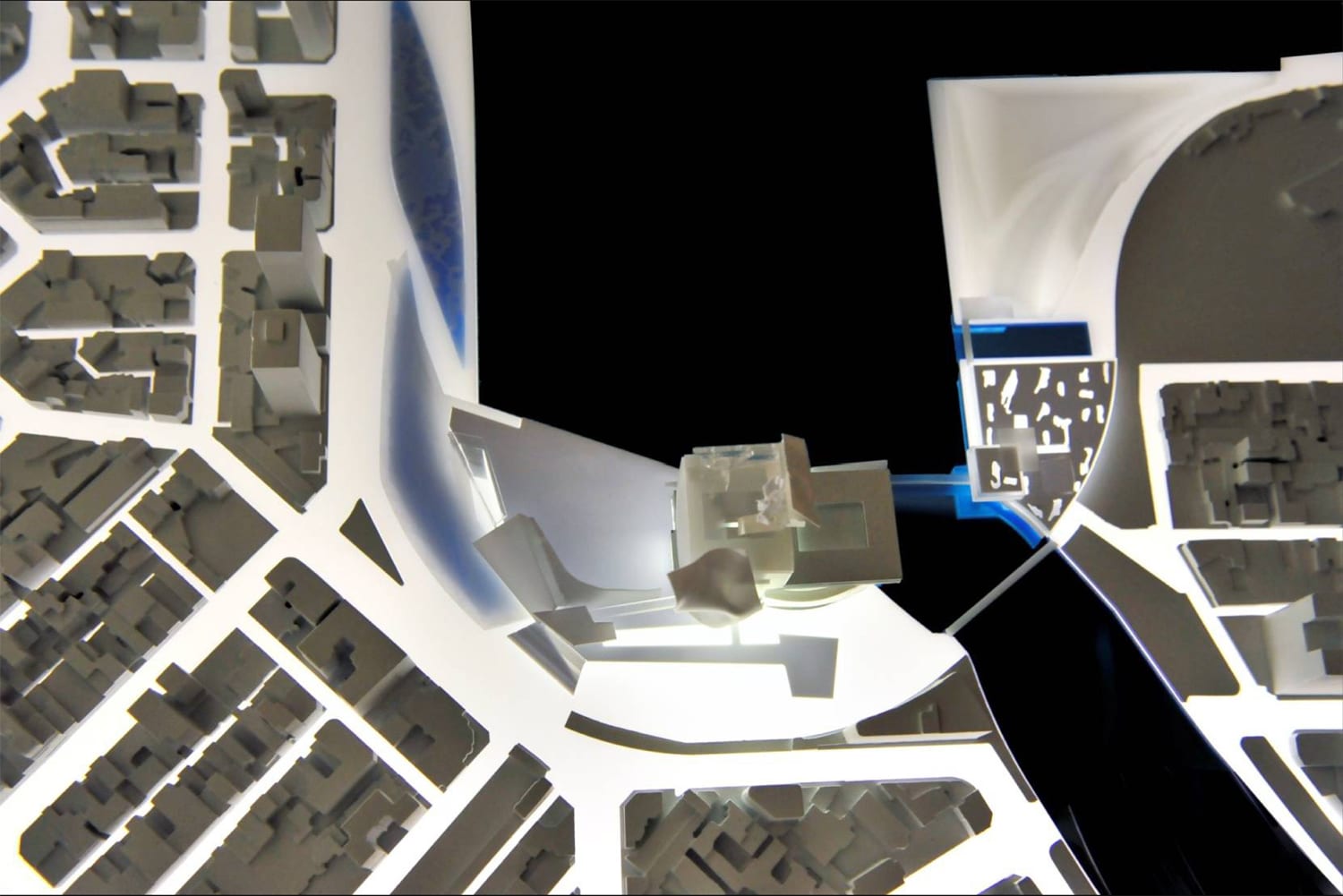

Rather than concentrating most of the programs within a limited area on the site, the entry by the Spanish team, led by Manuel Monteserín, suggested spreading the different program elements to venues surrounding the lagoon, in a sense embracing it. Their scheme indicated three main zones of programmatic concentration:

Zone 1 includes the outdoor performance area (12,000 capacity), the large performance hall (5,000 capacity) and the Pop Music Exhibit Area, a continuous gesture that is anchored by the placement of two towers. Here the open outdoor performance area can also serve as a public park when large audiences are not present for performances.

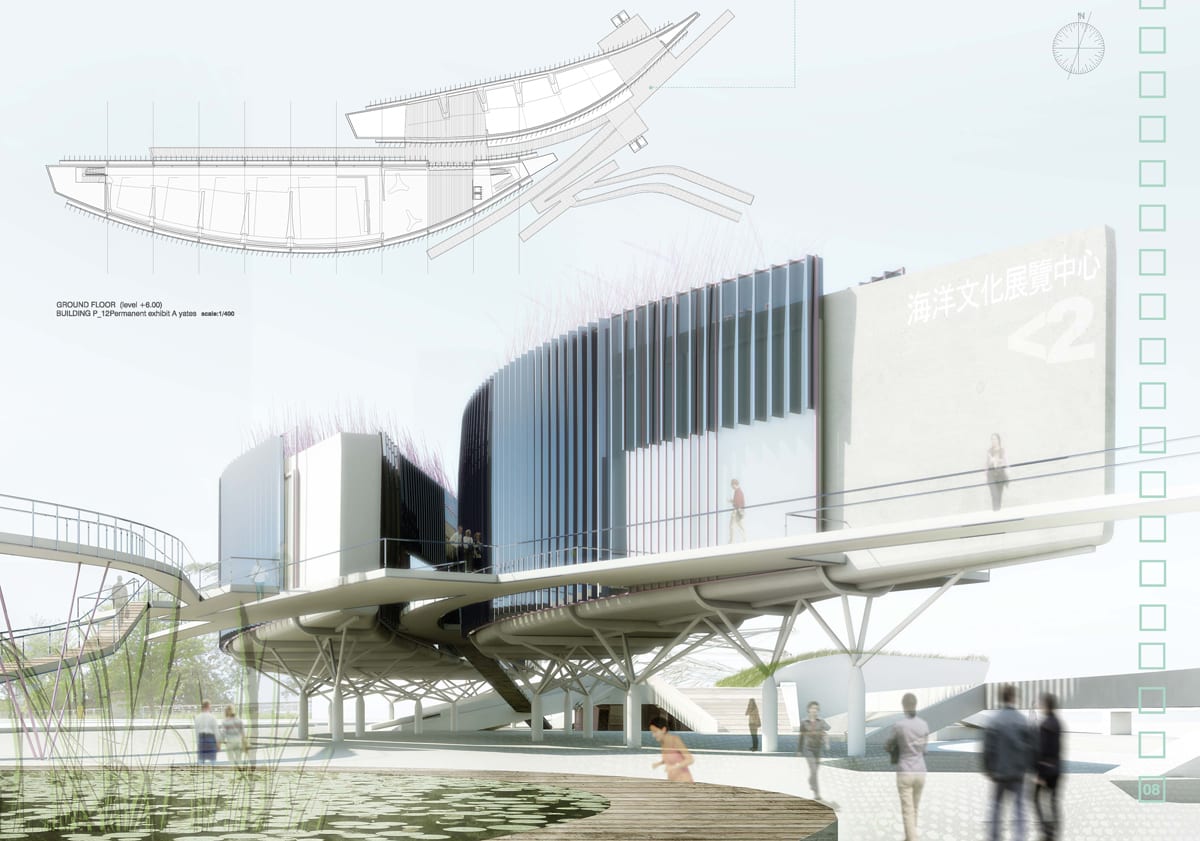

Zone 2 is home to a “night market,” a gathering place below the Marine Culture exhibit, a structure six meters with a walkway six meters high connecting the different pavilions. Part of this market area is under a canopy system with plantings, emphasizing its ecological character. The addition of a “night market” as gathering place was not in the program, but is undoubtedly one of those ideas which the jury took very seriously and may have tipped the scales in their favor.

Zone 3 was very linear in character, connecting two important poles of attraction, the new station for ferries to the south and the new night market in the north. This narrower stretch along the bay is home to galleries and eight small performance halls. There is a higher maritime walk and cycle lanes. This is a zone not only for relaxation, but contemplation, as it is on a more modest scale and at some distance from the nodes drawing larger crowds.

This entry was a rather daring, but a well conceived approach to the program. It was spread out in a very logical, creative manner, providing each venue with what appeared to be an optimal location based on its functions. Moreover, the architecture itself makes a strong cultural statement, but its expression and transparency is well synchronized with the landscape, all the time keeping in mind that transition from land to water.

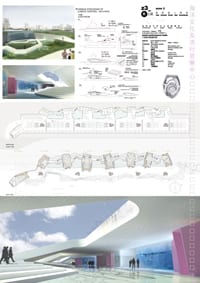

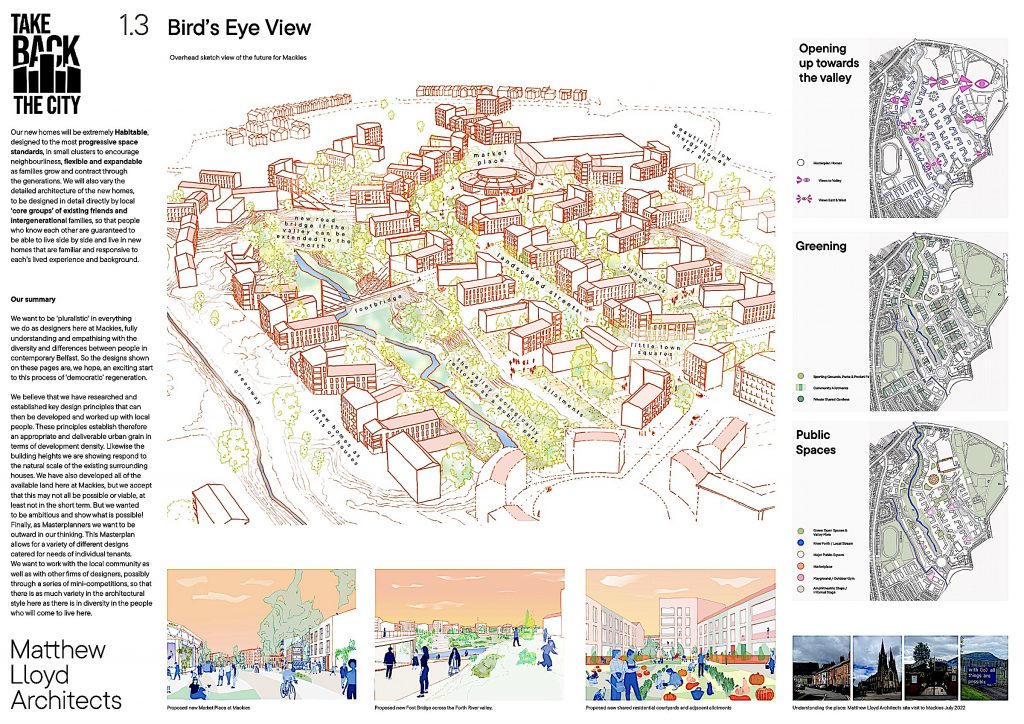

Second Place

Akihisa Hirata’s “Foam Form” design emphasized the organic, ecological nature of the plan. Scattered around the edge of the bay similar to the winning design, the main difference here is the prioritizing of the venues. Instead of galleries and smaller performance venues along the eastern shore, here the “Industrial Area” and landscape take over. The Pop Music Exhibition area is located to the north, near the Small Auditorium. The most interesting architectural creation has to be the Landscape Bridge as a connecting link across the river. Not just a connecting link, it also can be seen as an element one might encounter in a theme park. If the intent of the author of the design is to blur the connection between city and nature, this might represent a successful strategy. Though adventuresome in another way, it falls short of the powerful language common to the winning design.

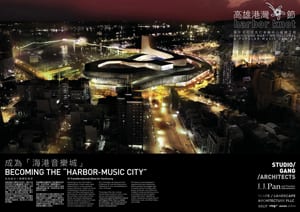

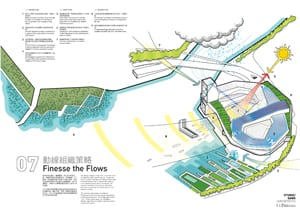

Third Place

The entry by Studio Gang Architects differs in that it places most of the action within a more limited area at the top of the site. In crafting their proposal, Studio Gang listed several guidelines which were highlighted as guiding principles of their design:

01 Tie into the Urban Network

02 Reclaim the Edge

03 Make Architecture an Adventure

04 Shape Spectacular Voids

05 Amplify the Harbor’s Kinetics

06 Tower Power

07 Finesse the Flows

08 Improve H2O

09 Shade = Urbanism

10 Made in Taiwan

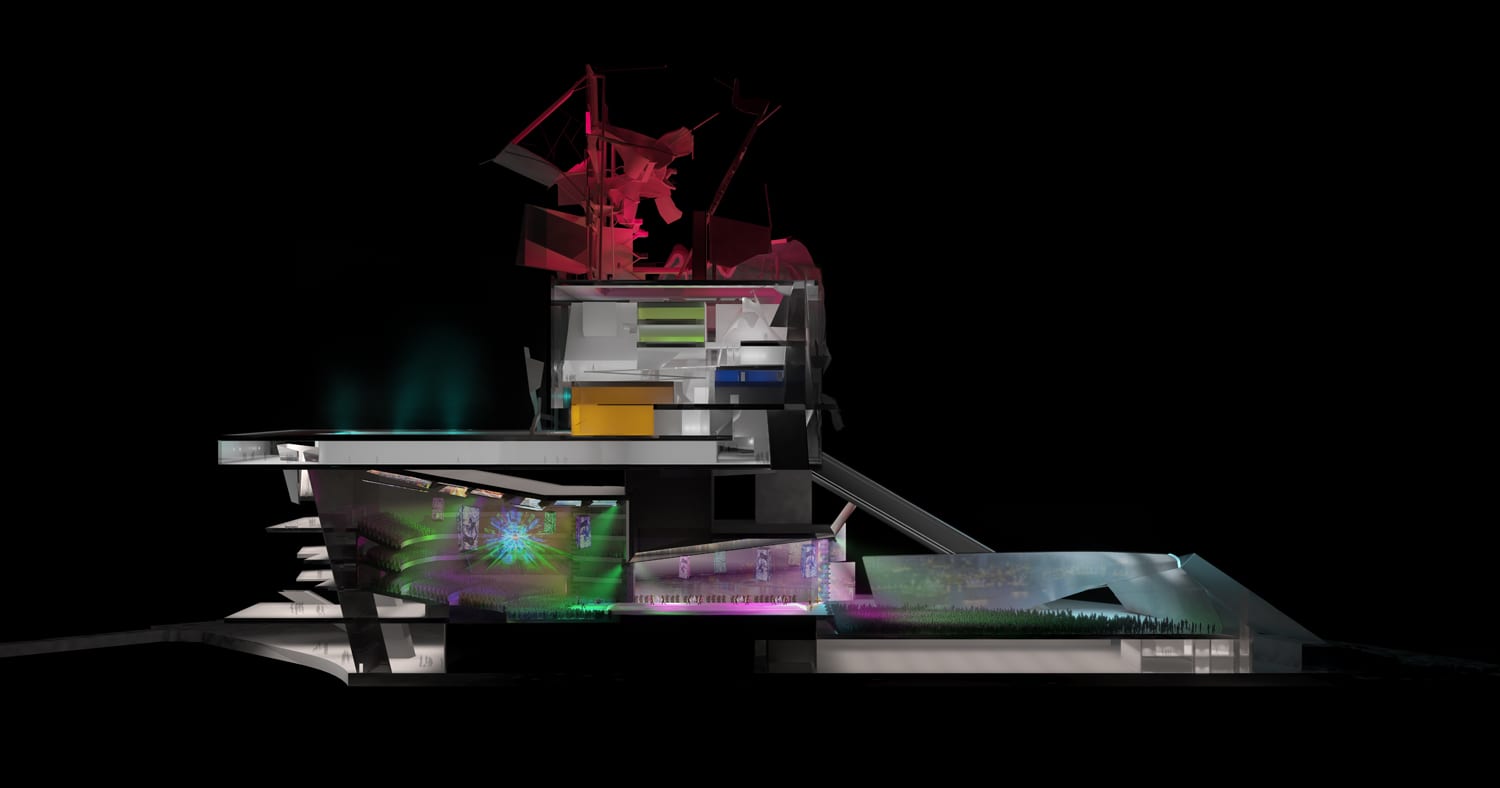

By locating much of the program — and the energy — at the northernmost point on the site, the machine-like image projected is as much about tourism as it is a connection to the water’s edge. This represents an urban experience which is totally different from the two preceding designs. It is much more ‘in your face’ and not as relaxed as it predecessors. Apart from the configuration of the main structure, it tends to be a more conventional approach to the program. Yes, there are several outdoor venues to be enjoyed; but does this main structure represent a seamless transition from industrial urban to harbor? This design reminds one of the top contending designs which Studio Gang submitted for the Taiwan Pop Music Center competition. There, this type of approach seemed more appropriate. But it certainly was interesting to see how such an approach would fit in here.

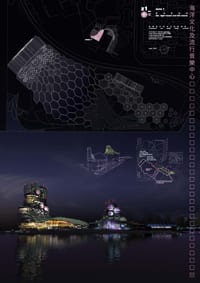

Honorable Mention I

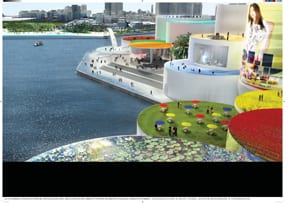

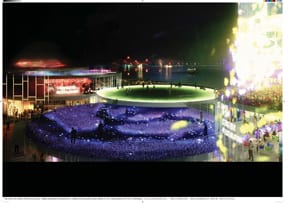

The Yves Bachmann with Toshihiro Kubota entry is a high density program at the northern area of the site. Containing cylindrical structures with rooftop platform areas for viewing and performing, this approach settled on two major areas of activity, “the encounter of Kaohsiung Maritime Cultural and the Popular Music Center.” The designers added abundant color as a visual moment, adding energy to the Pop Music theme. Still, the high density idea would seem to depend on a high volume of traffic.

Honorable Mention II

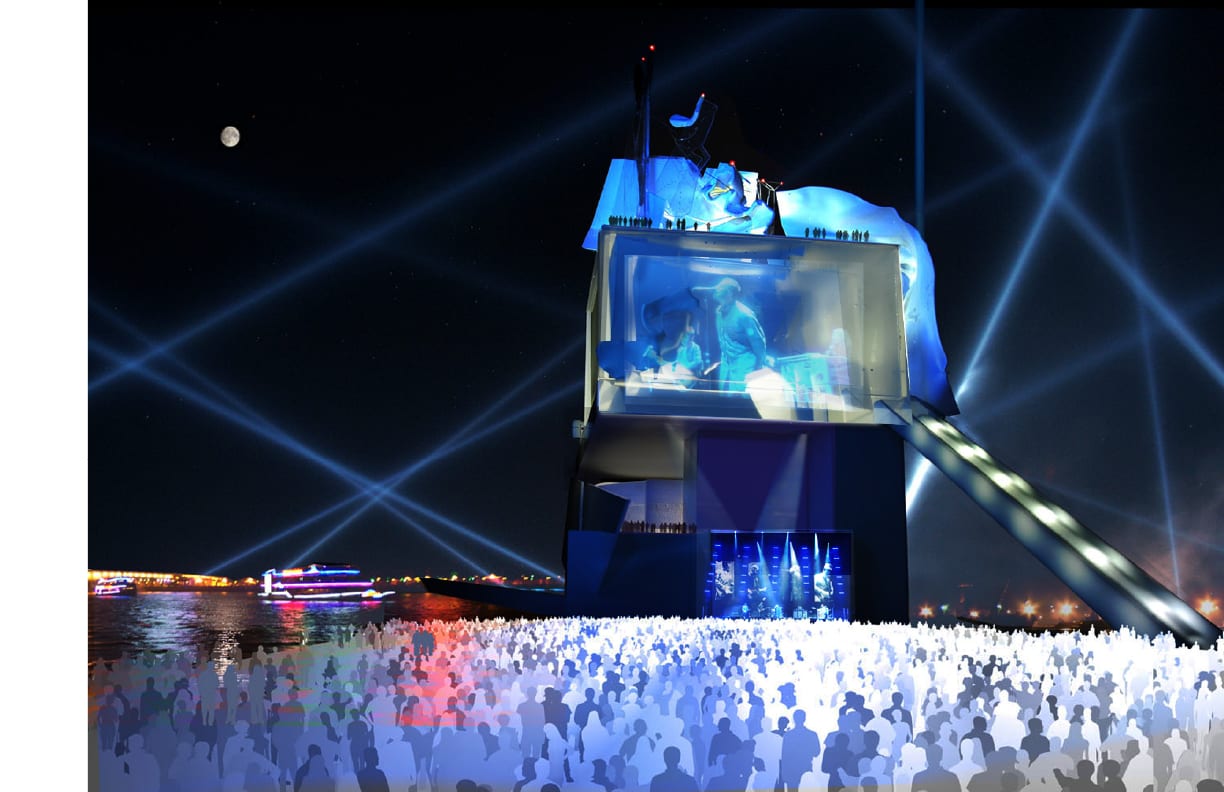

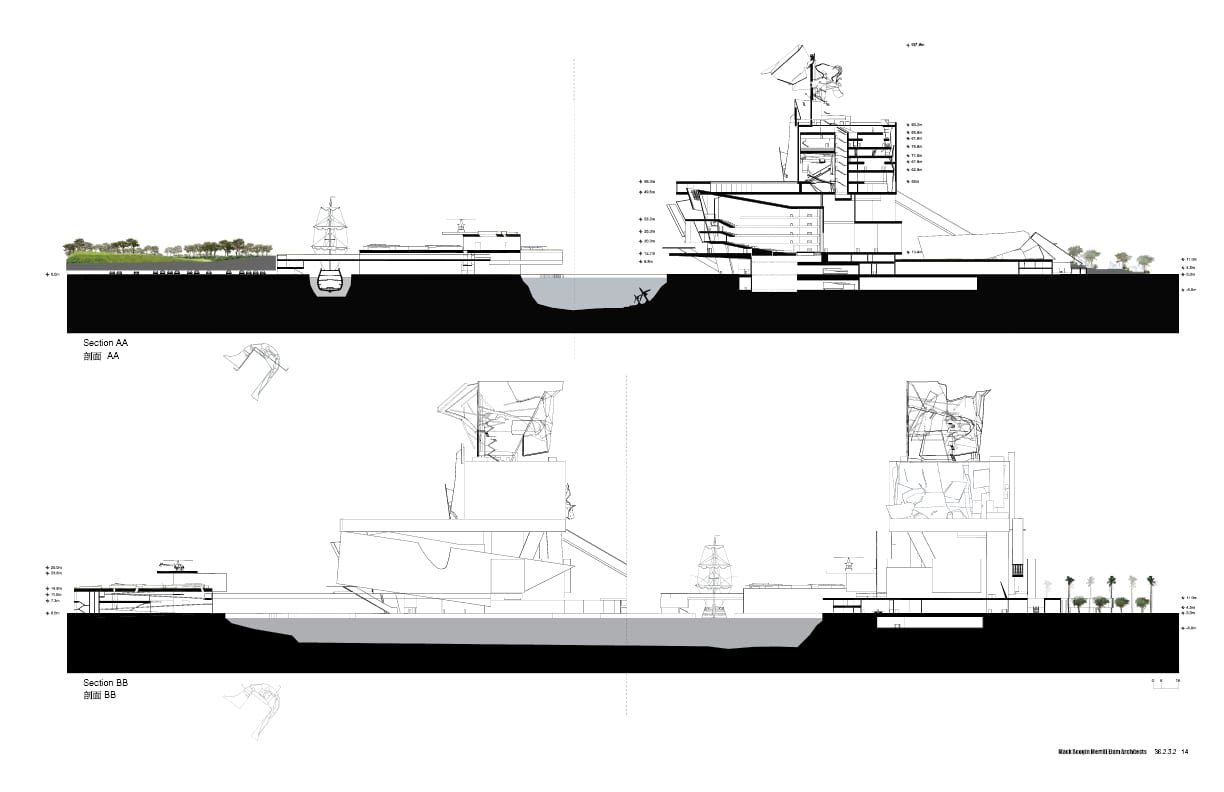

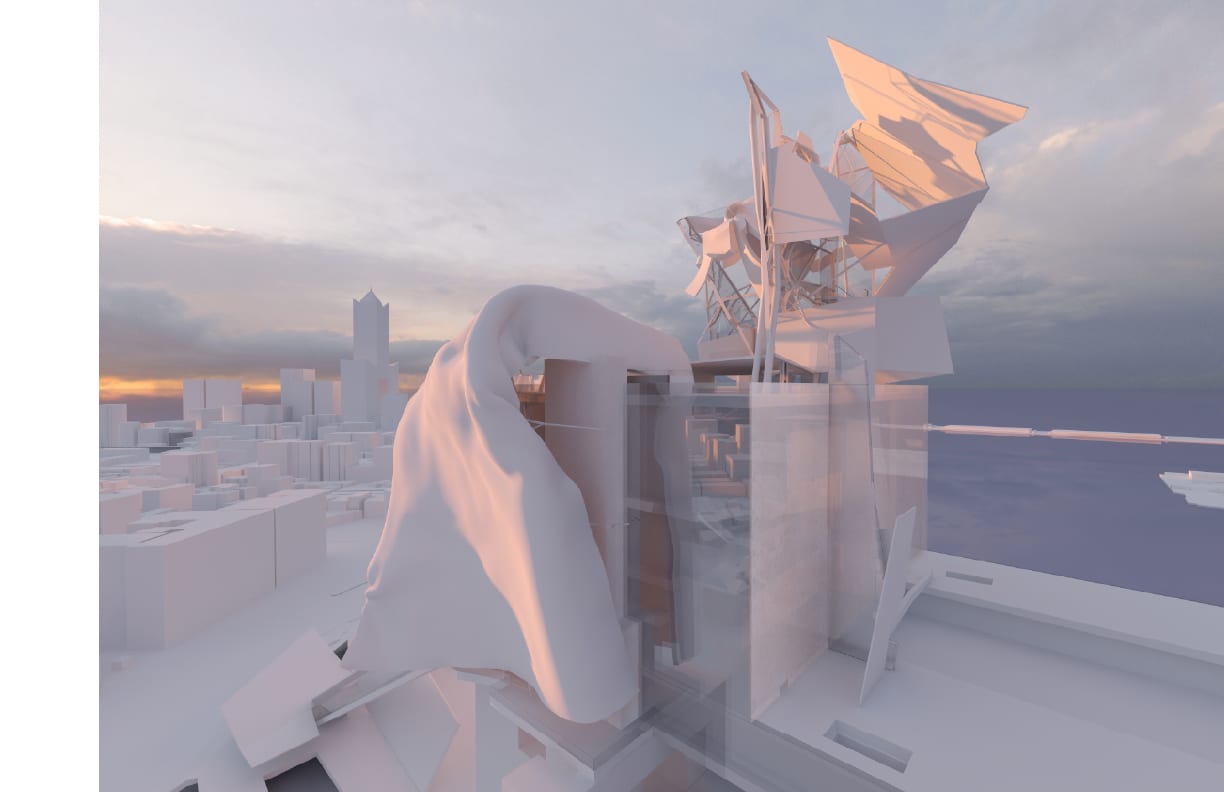

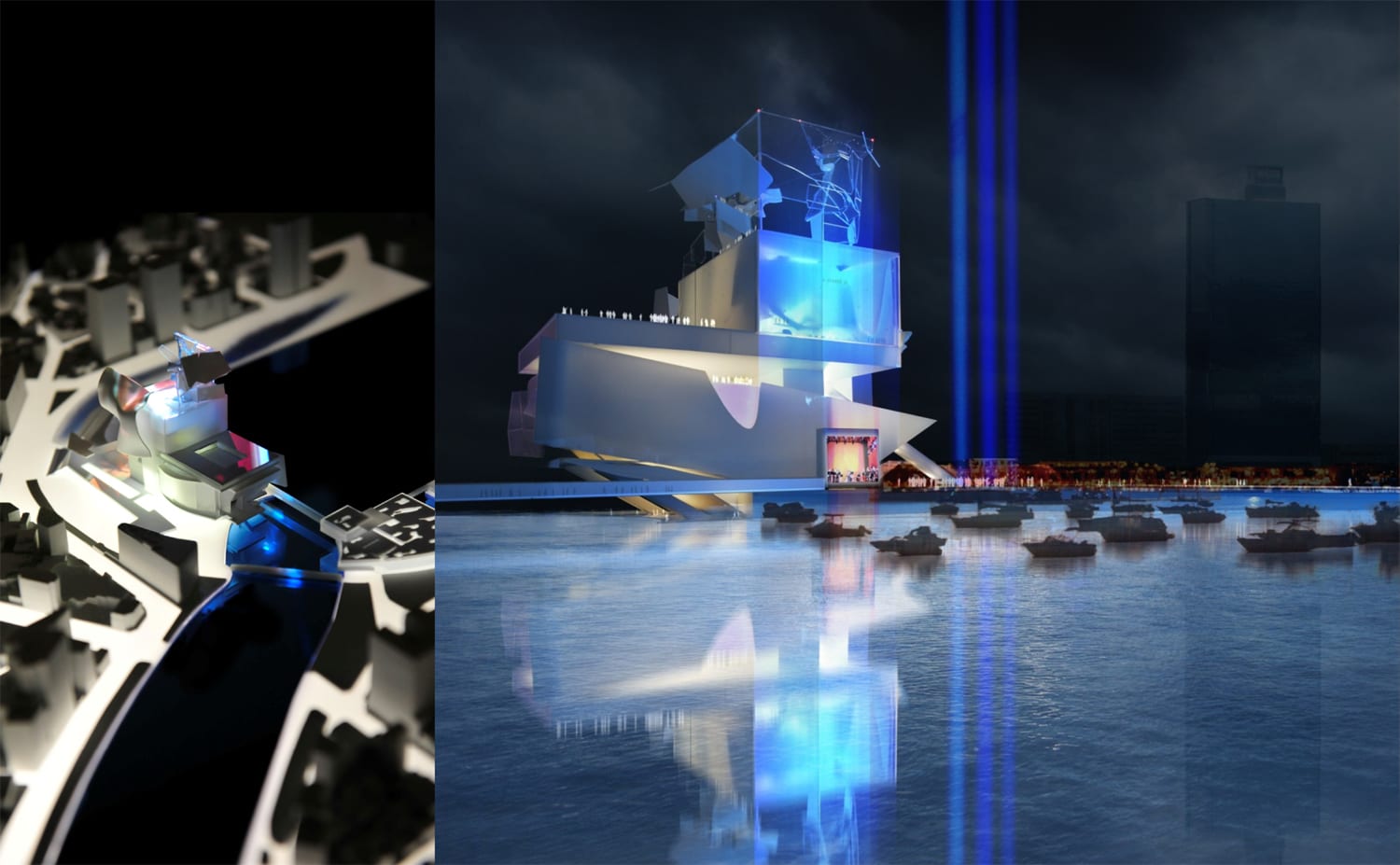

The proposal by Mac Scogin was also based on a high density solution, leaving 87% of the space on the site open for park activity or for future development. The two main programmatic components are situated on each side of the Love River, with the main iconic structure on the eastern side containing most of the music programs vertically. The connecting feature of the large and smaller performing venues in this area allows for larger crowds up to 17,000, not including those who might watch from boats in the harbor.

Summary

One may only assume that the horizontal schemes of the First and Second Place winners were preferred over the higher density proposals of the other finalists. By inserting a large market venue at the apex of the site, the winning team from Spain no doubt helped their cause immeasurably. It serves not only as an ideal meeting place, but smoothes the transition from city to water.